Battle of Fort Blakeley

Fortifications at Blakeley

The Battle of Fort Blakeley, fought on April 9, 1865, was the climax of the U.S. military campaign during the Civil War aimed at capturing the city of Mobile, the last major port that remained in Confederate hands. The battle took place at the site of Fort Blakeley, an earthen Confederate fortification about six miles north of present-day Spanish Fort in Baldwin County. In it, some 16,000 federal troops fought against approximately 3,500 Confederates, with the U.S. military gaining a decisive victory and taking the city of Mobile soon after. The site is now commemorated as Historic Blakeley State Park.

Fortifications at Blakeley

The Battle of Fort Blakeley, fought on April 9, 1865, was the climax of the U.S. military campaign during the Civil War aimed at capturing the city of Mobile, the last major port that remained in Confederate hands. The battle took place at the site of Fort Blakeley, an earthen Confederate fortification about six miles north of present-day Spanish Fort in Baldwin County. In it, some 16,000 federal troops fought against approximately 3,500 Confederates, with the U.S. military gaining a decisive victory and taking the city of Mobile soon after. The site is now commemorated as Historic Blakeley State Park.

The city of Mobile was a vital transportation and supply center in the South, and federal forces had been planning to capture it as early as 1862. Owing to several factors, however, they were unable to put their plans in motion until the summer of 1864. This delay allowed Confederate forces to transform the Mobile Bay area into one of the most heavily fortified regions of the country. Three lines of substantial fortifications ringed the city itself, and strategically located artillery batteries, rows of pilings, and floating mines protected the approach from the bay. Following the Battle of Mobile Bay in August 1864 and the capture of Confederate positions in the lower bay (including Forts Morgan and Gaines), federal forces made plans to advance towards the city from the east. Two major but as yet unfinished defensive positions along the eastern shore in Baldwin County, known as Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley (commonly misspelled as “Blakely”), stood in their way.

Mobile’s Eastern Defenses

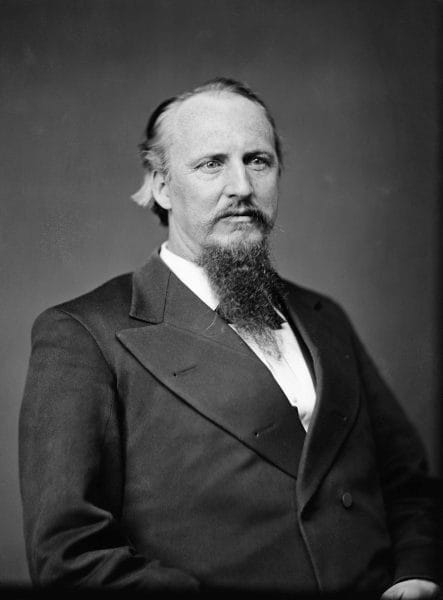

Dabney H. Maury

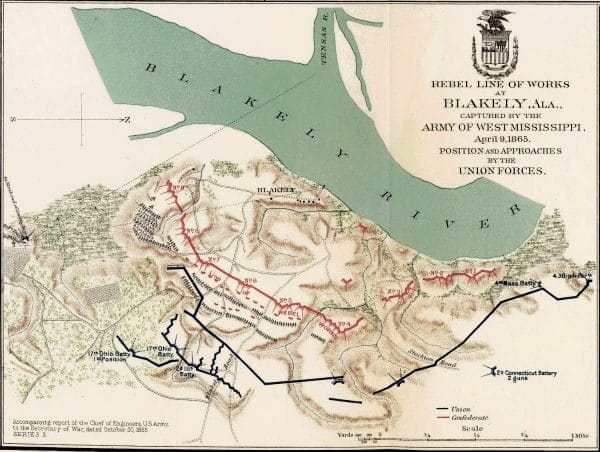

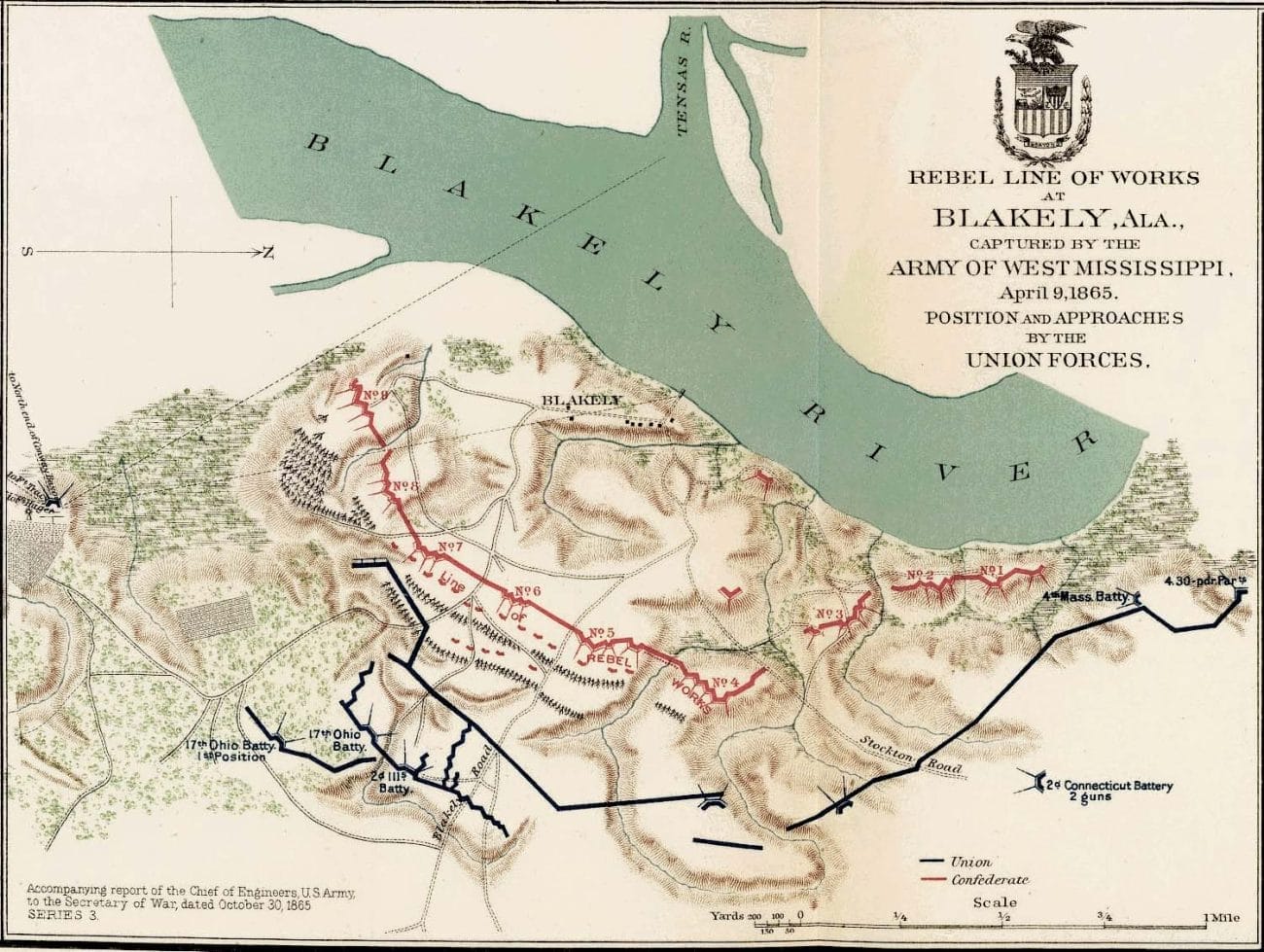

Built near the site of a Revolutionary War outpost constructed by the Spanish after their capture of British Mobile and known as “Spanish Fort,” the structure consisted of three linked earthen forts overlooking a series of bluffs along the Blakeley River. About five miles to its north stood Fort Blakeley, an earthworks constructed under the direction of Virginian major general Dabney H. Maury by Confederate soldiers and enslaved men pressed into service. The structure consisted of an arcing three-mile line of entrenchments anchored by nine redoubts and about 40 pieces of artillery. The outpost received its name from the nearby river community of Blakeley, then seat of Baldwin County. Its location along a stretch of high ground and a deep water port at the intersection of the Stockton and Pensacola Roads nevertheless made it a strategic defensive position. Confederate forces under the overall command of Maury occupied the eastern shore defenses, including about 2,500 men at Spanish Fort and a similar number at Fort Blakeley. After a nearly two-week siege at Spanish Fort, Brig. Gen. Randall Gibson, severely outnumbered and with his lines on the verge of breaking, had skillfully evacuated the outpost on the night of April 8, 1865, and left it for the federal troops. At that point, Fort Blakeley became the only major Confederate post defending Mobile.

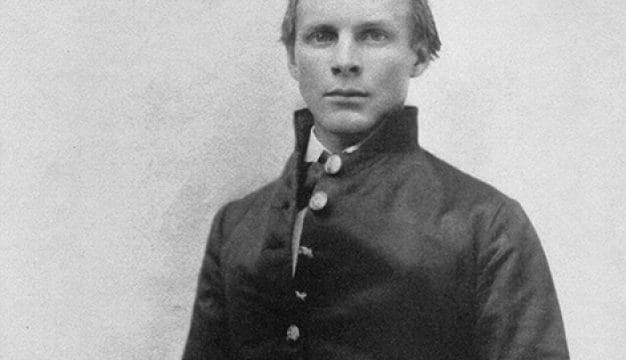

Dabney H. Maury

Built near the site of a Revolutionary War outpost constructed by the Spanish after their capture of British Mobile and known as “Spanish Fort,” the structure consisted of three linked earthen forts overlooking a series of bluffs along the Blakeley River. About five miles to its north stood Fort Blakeley, an earthworks constructed under the direction of Virginian major general Dabney H. Maury by Confederate soldiers and enslaved men pressed into service. The structure consisted of an arcing three-mile line of entrenchments anchored by nine redoubts and about 40 pieces of artillery. The outpost received its name from the nearby river community of Blakeley, then seat of Baldwin County. Its location along a stretch of high ground and a deep water port at the intersection of the Stockton and Pensacola Roads nevertheless made it a strategic defensive position. Confederate forces under the overall command of Maury occupied the eastern shore defenses, including about 2,500 men at Spanish Fort and a similar number at Fort Blakeley. After a nearly two-week siege at Spanish Fort, Brig. Gen. Randall Gibson, severely outnumbered and with his lines on the verge of breaking, had skillfully evacuated the outpost on the night of April 8, 1865, and left it for the federal troops. At that point, Fort Blakeley became the only major Confederate post defending Mobile.

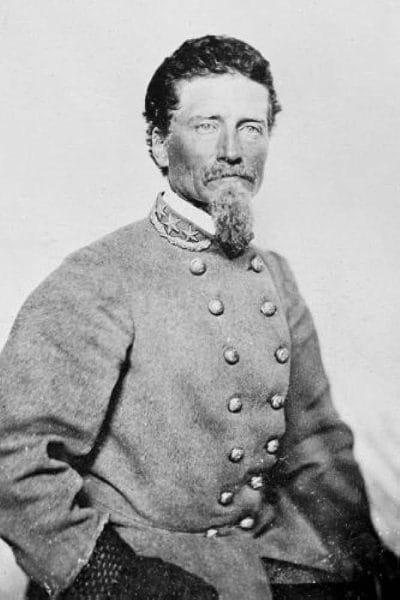

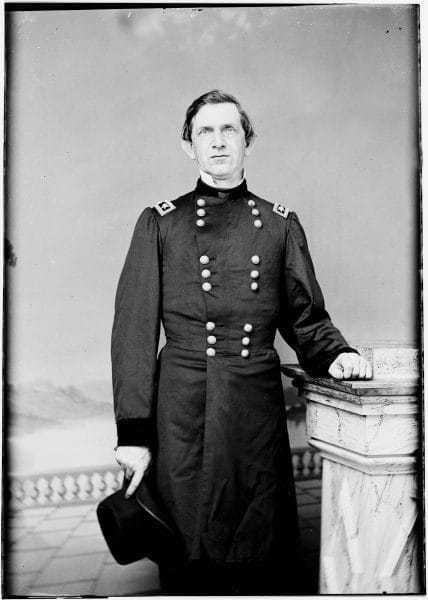

Francis M. Cockrell

The Confederacy’s Brig. Gen. St. John R. Liddell commanded the roughly 3,500 men at Blakeley at the time of the battle, a portion of whom had made their way there after the fall of Spanish Fort. Included in Liddell’s command were two brigades under the direction of Brig. Gen. Francis M. Cockrell and composed primarily of veteran Missouri and Mississippi troops as well as two regiments of “Alabama Brigade” reserves, primarily teenage conscripts, under Brig. Gen. Bryan Thomas. Cockrell’s men occupied the Confederate center and left, while Thomas’s men gathered on the right. Liddell’s men had cleared trees and brush in front of the main line up to a distance of 800 yards to create clear fields of fire and had erected two lines of “abates” (tangles of fallen trees with branches pointed toward the enemy), sharpened stakes, and even telegraph wire strung between stumps to impede the attackers. They also dug a series of rifle pits, in which teams of skirmishers were deployed, a short distance in advance of these obstructions. Controversially, Liddell’s men had also buried dozens of land mines, a recent invention at the time called “subterra shells,” in the ground in their front. Nearby on islands in the Blakeley River were two large batteries, named Huger and Tracy, which formed an integral part of the overall Confederate line.

Francis M. Cockrell

The Confederacy’s Brig. Gen. St. John R. Liddell commanded the roughly 3,500 men at Blakeley at the time of the battle, a portion of whom had made their way there after the fall of Spanish Fort. Included in Liddell’s command were two brigades under the direction of Brig. Gen. Francis M. Cockrell and composed primarily of veteran Missouri and Mississippi troops as well as two regiments of “Alabama Brigade” reserves, primarily teenage conscripts, under Brig. Gen. Bryan Thomas. Cockrell’s men occupied the Confederate center and left, while Thomas’s men gathered on the right. Liddell’s men had cleared trees and brush in front of the main line up to a distance of 800 yards to create clear fields of fire and had erected two lines of “abates” (tangles of fallen trees with branches pointed toward the enemy), sharpened stakes, and even telegraph wire strung between stumps to impede the attackers. They also dug a series of rifle pits, in which teams of skirmishers were deployed, a short distance in advance of these obstructions. Controversially, Liddell’s men had also buried dozens of land mines, a recent invention at the time called “subterra shells,” in the ground in their front. Nearby on islands in the Blakeley River were two large batteries, named Huger and Tracy, which formed an integral part of the overall Confederate line.

The U.S. Army Attacks

Edward R. S. Canby

Moving against these defenses were more than 40,000 troops under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Edward R. S. Canby. Canby’s main column advanced north from Fort Morgan, which guarded the eastern side of the entrance to Mobile Bay, in mid-March 1865; a second force, led by Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele, was making its way west from Pensacola, having fought several small but sharp engagements along the way. Steele arrived at Fort Blakeley on April 1, 1865, and immediately began to lay siege. His numbers were soon augmented by detachments from Canby’s force at Spanish Fort, bringing the total number of attackers to some 16,000. Included in the federal ranks were some 5,000 men of the “United States Colored Troops (USCT),” African American regiments composed in large part of former enslaved and free blacks from the South. Their presence at Blakeley ranks among the heaviest concentrations of African American soldiers who participated in any one battle during the Civil War. The armies skirmished day and night for more than a week as the federal engineers constructed three parallel systems of earthworks located progressively closer to the Confederate position. Liddell’s men attempted to slow the U.S. troops’ advance under cover of dark by launching several small scale sorties and periodically lobbing “fire balls” (artillery shells filled with quicklime, CaO, that gave a brief, intense glow as they burned) into the air to temporarily illuminate their targets. They also enlisted the aid of Confederate ships, including the CSS Huntsville, Nashville, and Gaines, lying in the Tensaw River, which shelled the federal lines until eventually driven off by artillery.

Edward R. S. Canby

Moving against these defenses were more than 40,000 troops under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Edward R. S. Canby. Canby’s main column advanced north from Fort Morgan, which guarded the eastern side of the entrance to Mobile Bay, in mid-March 1865; a second force, led by Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele, was making its way west from Pensacola, having fought several small but sharp engagements along the way. Steele arrived at Fort Blakeley on April 1, 1865, and immediately began to lay siege. His numbers were soon augmented by detachments from Canby’s force at Spanish Fort, bringing the total number of attackers to some 16,000. Included in the federal ranks were some 5,000 men of the “United States Colored Troops (USCT),” African American regiments composed in large part of former enslaved and free blacks from the South. Their presence at Blakeley ranks among the heaviest concentrations of African American soldiers who participated in any one battle during the Civil War. The armies skirmished day and night for more than a week as the federal engineers constructed three parallel systems of earthworks located progressively closer to the Confederate position. Liddell’s men attempted to slow the U.S. troops’ advance under cover of dark by launching several small scale sorties and periodically lobbing “fire balls” (artillery shells filled with quicklime, CaO, that gave a brief, intense glow as they burned) into the air to temporarily illuminate their targets. They also enlisted the aid of Confederate ships, including the CSS Huntsville, Nashville, and Gaines, lying in the Tensaw River, which shelled the federal lines until eventually driven off by artillery.

The U.S. military command began its final assault on Fort Blakeley on the afternoon of Sunday, April 9, 1865. Unknown to either army, that very day Confederate commander general Robert E. Lee had surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Heavy fighting began around 3 p.m. on the Confederate left as a portion of the federal besiegers, including several units of the USCT, probed Blakeley’s defenses. The full assault began about 5:30 p.m. Across a nearly three-mile-long front, federal troops emerged from trenches in places less than 1,000 yards from the fort’s defenders and charged. They began taking casualties almost immediately, coming under rifle and artillery fire as well as tripping some of the land mines. The surging federal army nevertheless soon reached the Confederate skirmishers, who were forced to retreat to the main line. Their comrades had to hold their fire to avoid hitting the retreating troops, allowing the attackers to begin cutting through the lines of abates in front of the earthworks.

Blakeley Falls

Historic Blakeley State Park

Once the federal troops reached the Confederate line, fierce, close-quarters combat briefly raged. Some defenders threw down their arms and surrendered or turned and ran after federal troops had overrun their position, but others fought on even after being surrounded. Despite their resistance, the federal attackers overwhelmed the Confederate line and the fighting was over within 30 minutes. A very small number of Confederate soldiers, perhaps a few dozen, escaped via the river. The great majority of the garrison was captured. Exact numbers of casualties are unknown, but it is believed that about 75 Confederate defenders were killed, and Union attackers suffered about 150 killed and around 650 wounded during the entirety of the siege and assault. Some of the U.S. casualties occurred after the battle, as the mine-ridden battlefield continued to claim victims until captured prisoners were forced to point out their locations. Allegations that some Confederates were shot even after they surrendered to USCT troops surfaced almost immediately after the battle and the truth of what happened in its chaotic last moments continues to be the subject of research and speculation today. Available evidence indicates some federal soldiers indeed may have fired on Confederates who had surrendered, but there was no large-scale massacre. Several federal soldiers were later recognized with the Congressional Medal of Honor for their bravery during the assault or for having captured flags at Blakeley. With the fall of both Fort Blakeley and Spanish Fort, Batteries Huger and Tracy were both rendered essentially useless and were abandoned two days later. On April 12, the mayor of Mobile surrendered the city to U.S. military forces.

Historic Blakeley State Park

Once the federal troops reached the Confederate line, fierce, close-quarters combat briefly raged. Some defenders threw down their arms and surrendered or turned and ran after federal troops had overrun their position, but others fought on even after being surrounded. Despite their resistance, the federal attackers overwhelmed the Confederate line and the fighting was over within 30 minutes. A very small number of Confederate soldiers, perhaps a few dozen, escaped via the river. The great majority of the garrison was captured. Exact numbers of casualties are unknown, but it is believed that about 75 Confederate defenders were killed, and Union attackers suffered about 150 killed and around 650 wounded during the entirety of the siege and assault. Some of the U.S. casualties occurred after the battle, as the mine-ridden battlefield continued to claim victims until captured prisoners were forced to point out their locations. Allegations that some Confederates were shot even after they surrendered to USCT troops surfaced almost immediately after the battle and the truth of what happened in its chaotic last moments continues to be the subject of research and speculation today. Available evidence indicates some federal soldiers indeed may have fired on Confederates who had surrendered, but there was no large-scale massacre. Several federal soldiers were later recognized with the Congressional Medal of Honor for their bravery during the assault or for having captured flags at Blakeley. With the fall of both Fort Blakeley and Spanish Fort, Batteries Huger and Tracy were both rendered essentially useless and were abandoned two days later. On April 12, the mayor of Mobile surrendered the city to U.S. military forces.

Further Reading

- Bunn, Mike. The Assault on Fort Blakeley: The Thunder and Lightning of Battle. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2021.

- Noles, Jim. “Confederate Twilight: The Fall of Fort Blakeley.” Alabama Heritage (Winter 2009): 28-37.

- O’Brien, Sean Michael. Mobile, 1865: Last Stand of the Confederacy. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2001.