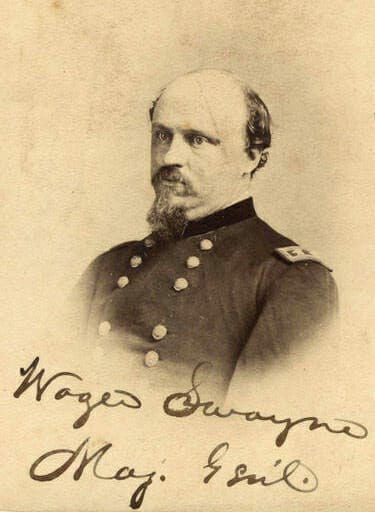

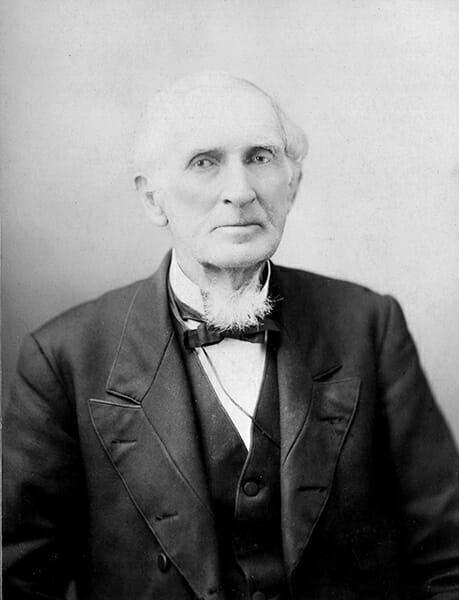

Wager T. Swayne

Wager Swayne

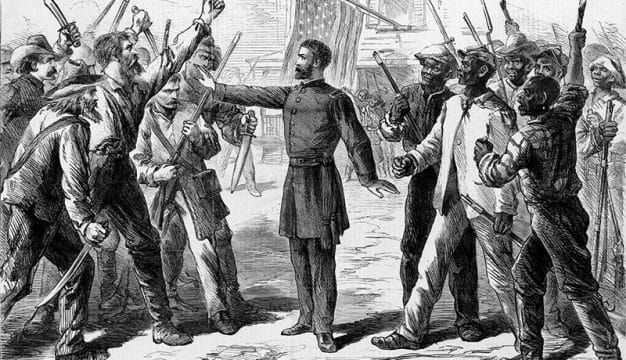

General Wager T. Swayne (1834-1902), often referred to as Alabama’s military governor, never formally held that title. Nonetheless, he wielded substantial executive authority as assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau for Alabama during the early years of Reconstruction under the provisional governor, Lewis E. Parsons, and his successor, Gov. Robert M. Patton.

Wager Swayne

General Wager T. Swayne (1834-1902), often referred to as Alabama’s military governor, never formally held that title. Nonetheless, he wielded substantial executive authority as assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau for Alabama during the early years of Reconstruction under the provisional governor, Lewis E. Parsons, and his successor, Gov. Robert M. Patton.

Wager Swayne was born on November 10, 1834, in New York City, but grew up in Columbus, Ohio. His parents, Noah Haynes Swayne and Sarah Ann Swayne, were native Virginians who liberated the enslaved people they owned and relocated to Ohio, where Noah Swayne became prominent in Republican politics and eventually was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by Abraham Lincoln. Thus young Wager Swayne was raised with both antislavery convictions and influential Republican connections.

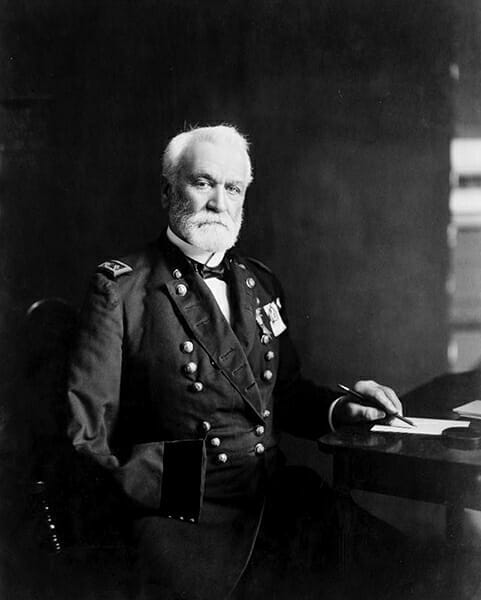

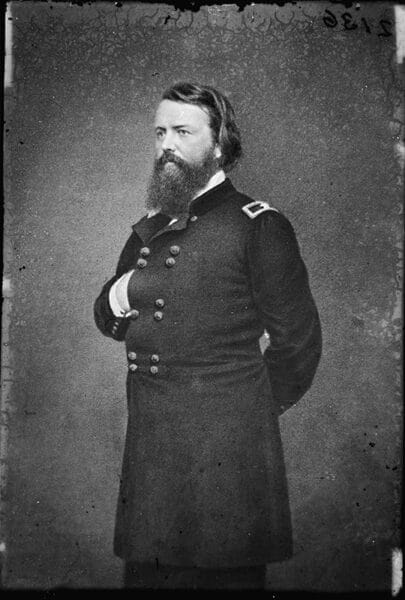

Oliver O. Howard

Swayne graduated from Yale University in 1856 and the Cincinnati Law School in 1859, and entered the practice of law with his father. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined the army and commanded the Forty-third Ohio Volunteer Regiment through much of the war. He rose to the rank of brigadier general and eventually won the Congressional Medal of Honor for leading a charge at Corinth, Mississippi, in October 1862. Late in the war, Swayne lost his right leg at Rivers Bridge in South Carolina. A committed Episcopalian, the general’s religious bearing under duress won the admiration of his equally devout superior officer, Gen. Oliver O. Howard. After the war, Howard was appointed head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was created to supervise emancipation, and he appointed his convalescing subordinate to the post of assistant commissioner for Alabama.

Oliver O. Howard

Swayne graduated from Yale University in 1856 and the Cincinnati Law School in 1859, and entered the practice of law with his father. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined the army and commanded the Forty-third Ohio Volunteer Regiment through much of the war. He rose to the rank of brigadier general and eventually won the Congressional Medal of Honor for leading a charge at Corinth, Mississippi, in October 1862. Late in the war, Swayne lost his right leg at Rivers Bridge in South Carolina. A committed Episcopalian, the general’s religious bearing under duress won the admiration of his equally devout superior officer, Gen. Oliver O. Howard. After the war, Howard was appointed head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was created to supervise emancipation, and he appointed his convalescing subordinate to the post of assistant commissioner for Alabama.

Wager Swayne

Arriving in Montgomery in July 1865, Swayne discovered his new agency underfunded and in disorder. He promptly decided to cooperate with Alabama’s civil officials under Presidential Reconstruction. He urged emancipated slaves to sign contracts and go back to work, even prodding them with the threat of arrest. Authorized by law to establish army courts to protect the newly emancipated population, he instead offered to acknowledge the authority of civil tribunals but only if they agreed to accept black testimony. He also appointed Alabama officials as local Freedmen’s Bureau agents if they agreed to these terms. Provisional governor Lewis E. Parsons endorsed Swayne’s approach and termed his conduct “eminently satisfactory.” This characterization was borne out when Swayne lobbied behind the scenes during the constitutional convention of September 1865 to forestall some of the extreme racial legislation adopted in other southern states. Parsons and Swayne also cooperated on political matters, such as facilitating state efforts at famine relief, and Swayne assisted the governor in lobbying President Andrew Johnson to recognize the new Alabama constitution.

Wager Swayne

Arriving in Montgomery in July 1865, Swayne discovered his new agency underfunded and in disorder. He promptly decided to cooperate with Alabama’s civil officials under Presidential Reconstruction. He urged emancipated slaves to sign contracts and go back to work, even prodding them with the threat of arrest. Authorized by law to establish army courts to protect the newly emancipated population, he instead offered to acknowledge the authority of civil tribunals but only if they agreed to accept black testimony. He also appointed Alabama officials as local Freedmen’s Bureau agents if they agreed to these terms. Provisional governor Lewis E. Parsons endorsed Swayne’s approach and termed his conduct “eminently satisfactory.” This characterization was borne out when Swayne lobbied behind the scenes during the constitutional convention of September 1865 to forestall some of the extreme racial legislation adopted in other southern states. Parsons and Swayne also cooperated on political matters, such as facilitating state efforts at famine relief, and Swayne assisted the governor in lobbying President Andrew Johnson to recognize the new Alabama constitution.

Swayne continued to collaborate with Parsons’s elected successor, Gov. Robert M. Patton. Swayne’s early optimism about the prospects for black progress soon faded, however. Violence in the countryside toward the newly freed people escalated, and the civil authorities he had approved seemed less vigilant in protecting them. Furthermore, the newly elected legislature, once recognized by the president, ignored Swayne’s advice. The general convinced Governor Patton to veto several of the state’s more stringent “black codes,” pointing out the negative impact on northern public opinion.

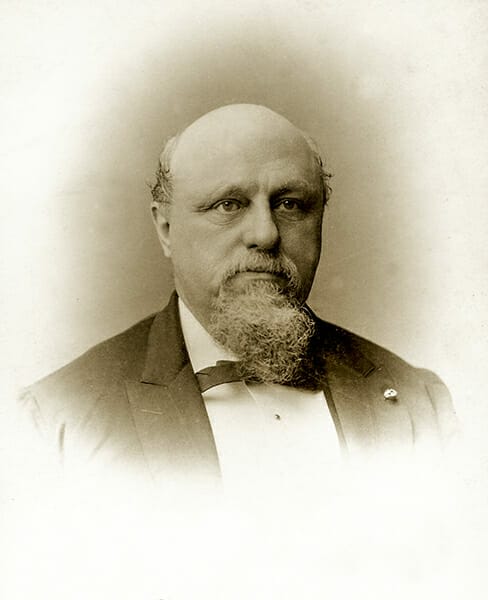

Robert M. Patton

By early 1866 Swayne accepted conflict with conservative whites as inevitable. Stymied in the political sphere, Swayne turned his attention toward providing education to emancipated slaves. He approached northern benevolent societies and churches for support, concluding that if black schools could be opened at no cost, the civil government would fund teachers rather than allow outsiders to fill those positions. Swayne, contrary to law, actually expended Freedmen’s Bureau money for the schools with the covert approval of General Howard.

Robert M. Patton

By early 1866 Swayne accepted conflict with conservative whites as inevitable. Stymied in the political sphere, Swayne turned his attention toward providing education to emancipated slaves. He approached northern benevolent societies and churches for support, concluding that if black schools could be opened at no cost, the civil government would fund teachers rather than allow outsiders to fill those positions. Swayne, contrary to law, actually expended Freedmen’s Bureau money for the schools with the covert approval of General Howard.

As the struggle between President Johnson and Congress intensified over the pace and reach of Reconstruction and with the Republican triumph in the 1866 congressional races, Swayne recognized that changes were coming. Swayne hoped the Alabama legislature might be intimidated and he pushed it to ratify the pending Fourteenth Amendment, which would grant citizenship to persons born in the United States, as a way to avoid even more drastic measures from the Congress. Despite the endorsement of Governor Patton, state legislators rejected the new constitutional amendment. This defeat persuaded Swayne that only black suffrage could force necessary changes, and continuing violence toward blacks provided him the “fullest evidence” that Alabama was “not very fit for a free government at all.”

John Pope

In March 1867, Congress took control of Reconstruction from President Johnson. Swayne, now military commander as well as bureau chief, enjoyed enhanced authority. He outlawed local governments’ use of the chain gang and released those who had been jailed as “vagrants” under Alabama’s black codes. He also restored the ability to use martial law to punish violent offenders. With the encouragement of his superior, General John Pope, commander of the Third Military District overseeing Alabama, Florida and Georgia, Swayne encouraged the new black electorate to organize. He appeared at numerous conventions and helped to create the Republican Party of Alabama at a state convention in June. Swayne’s office became forthrightly partisan: the state Republican Party’s Union League was organized by one of his employees, and Swayne’s superintendent of voter registration, William H. Smith, became the first republican governor of the state. In addition, three of the six Alabama congressmen elected under the initial Reconstruction elections were bureau agents, and Swayne even considered a run for one of the state’s U.S. Senate seats.

John Pope

In March 1867, Congress took control of Reconstruction from President Johnson. Swayne, now military commander as well as bureau chief, enjoyed enhanced authority. He outlawed local governments’ use of the chain gang and released those who had been jailed as “vagrants” under Alabama’s black codes. He also restored the ability to use martial law to punish violent offenders. With the encouragement of his superior, General John Pope, commander of the Third Military District overseeing Alabama, Florida and Georgia, Swayne encouraged the new black electorate to organize. He appeared at numerous conventions and helped to create the Republican Party of Alabama at a state convention in June. Swayne’s office became forthrightly partisan: the state Republican Party’s Union League was organized by one of his employees, and Swayne’s superintendent of voter registration, William H. Smith, became the first republican governor of the state. In addition, three of the six Alabama congressmen elected under the initial Reconstruction elections were bureau agents, and Swayne even considered a run for one of the state’s U.S. Senate seats.

Swayne’s political intervention, especially at the state’s constitutional convention of November 1867, drew the ire of conservatives and the attention of President Johnson. In December, the president ordered the removal of both Pope and Swayne. The general’s successor, General Julius Hayden, came to power on January 11, 1868, and moved to “purge the Bureau from all party affiliations.” The confusion of leadership facilitated the white conservative boycott of the constitutional ratification election of 1868, thus preventing the constitution from receiving the required majority needed for ratification. Congress, nonetheless, admitted Alabama under the Republican constitution in July 1868.

In December 1868, Swayne married Ellen Harris of Louisville, Kentucky. After being reassigned to his army unit, he served in the West until 1870, when he retired from the military. He returned to the practice of law in Toledo, Ohio, and became a highly successful corporate attorney. Swayne relocated to New York City in 1881 and died there in 1902, a Republican to the end.

The reputation of Wager Swayne has enjoyed an odd fate at the hands of historians, who have generally stressed his early conciliatory policies toward Alabama’s postwar white government. At the turn of the century, Walter Lynwood Fleming praised his bureau as “probably the least harmful of all in the South,” whereas more recent scholars have seen him as insufficiently protective of emancipated slaves. Taking his career in Alabama as a whole, however, one should not overemphasize Swayne’s initial moderation. He was committed to the bureau’s goal of securing civil rights and moved toward more drastic means as increased obstructions blocked his efforts. He helped to create the Alabama Republican Party, and his activist policies laid the groundwork for expansion of public education to black children.

Further Reading

- Bethel, Elizabeth. “The Freedmen’s Bureau in Alabama.” Journal of Southern History 14 (February 1948): 49-92.

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. “Wager Swayne, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the Politics of Reconstruction in Alabama.” Alabama Review 48 (July 1995): 188-218.

- White, Kenneth B. “Wager Swayne: Racist or Realist?” Alabama Review 31 (April 1978): 92–105.