Charles Kleibacker

Three Cocktail Dresses, 1968-1978

Fashion designer, curator, and educator Charles Kleibacker (1921-2010) was renowned for his work in fashion design and for his creation of fluid garments of intricate cut and construction. His specialty was the use of the bias cut in day and evening dresses that were engineered to delineate a woman’s anatomy while providing ease and elegance to the wearer. In addition to his mastery of couture sewing techniques, Kleibacker developed innovative ways to drape cloth and assemble garments during his design career. He became a well-known figure in the highly competitive world of New York fashion, and his work can be found in numerous museums and costume collections in the United States.

Three Cocktail Dresses, 1968-1978

Fashion designer, curator, and educator Charles Kleibacker (1921-2010) was renowned for his work in fashion design and for his creation of fluid garments of intricate cut and construction. His specialty was the use of the bias cut in day and evening dresses that were engineered to delineate a woman’s anatomy while providing ease and elegance to the wearer. In addition to his mastery of couture sewing techniques, Kleibacker developed innovative ways to drape cloth and assemble garments during his design career. He became a well-known figure in the highly competitive world of New York fashion, and his work can be found in numerous museums and costume collections in the United States.

Charles Kleibacker, ca. 1960s

Born in Cullman, Cullman County, on November 20, 1921, Charles John Kleibacker grew up in the shadow of his uncle’s department store, Stiefelmeyer’s. He was the son of Charles Hudson Kleibacker and Frances Link; he had one sister. He graduated from St. Bernard Preparatory School in 1939 and pursued his education at the University of Notre Dame, graduating second in a class of 600 with a bachelor’s degree in journalism in December 1942. He then began a brief stint reporting for Alabama‘s Birmingham Age-Herald in 1943. Kleibacker moved to New York in the fall of 1944, and his professional activities shifted toward retailing and public relations. He was enrolled in New York University’s graduate program in retail merchandising from 1944 to 1946, taking classes in the evening so that he could work during the day to support this goal. He obtained a position as an advertising copywriter for Gimbels department stores, one of the world’s largest retailing corporations at that time, where advertising executive Bernice Fitz-Gibbon steered him toward fashion copy writing. In 1947, he became an advertising copywriter for DePinna, an exclusive Fifth Avenue store, followed by a short stint at the Revlon cosmetics company.

Charles Kleibacker, ca. 1960s

Born in Cullman, Cullman County, on November 20, 1921, Charles John Kleibacker grew up in the shadow of his uncle’s department store, Stiefelmeyer’s. He was the son of Charles Hudson Kleibacker and Frances Link; he had one sister. He graduated from St. Bernard Preparatory School in 1939 and pursued his education at the University of Notre Dame, graduating second in a class of 600 with a bachelor’s degree in journalism in December 1942. He then began a brief stint reporting for Alabama‘s Birmingham Age-Herald in 1943. Kleibacker moved to New York in the fall of 1944, and his professional activities shifted toward retailing and public relations. He was enrolled in New York University’s graduate program in retail merchandising from 1944 to 1946, taking classes in the evening so that he could work during the day to support this goal. He obtained a position as an advertising copywriter for Gimbels department stores, one of the world’s largest retailing corporations at that time, where advertising executive Bernice Fitz-Gibbon steered him toward fashion copy writing. In 1947, he became an advertising copywriter for DePinna, an exclusive Fifth Avenue store, followed by a short stint at the Revlon cosmetics company.

In December 1948, he relocated to San Francisco and became an assistant to cabaret singer Hildegarde Loretta Sell, known professionally simply as Hildegarde, and her partner-manager Anna Sosenko. Involved in public relations, booking, and secretarial work, he travelled extensively and was exposed to the world of custom-made high fashion, known as couture. Kleibacker’s visits to legendary Paris fashion houses changed his life: it was at the house of Christian Dior, where Hildegarde was a client, that he found his true calling.

Black Silk Gazar Dress, 1968

During the 1950s, Kleibacker gained hands-on knowledge and experience in both business and design. In April 1951, he founded Elliot-Charles, a custom order house at 106 East 60th Street in New York, with his cousin Louise Lawes (née Stiefelmeyer) and her husband Elliot Lawes. Kleibacker handled the publicity and business ends, and designer Charles Wetmore was hired as the designer. The business closed after a year and a half, and Kleibacker hired the Paris-trained technician at the head of the workroom, a talented Russian woman known as Madame Burg, to teach him the engineering aspects of design. This apprenticeship enabled him to design his own creations and produce them with Burg’s couture expertise. He then sold them to the exclusive Hattie Carnegie and Lord & Taylor stores.

Black Silk Gazar Dress, 1968

During the 1950s, Kleibacker gained hands-on knowledge and experience in both business and design. In April 1951, he founded Elliot-Charles, a custom order house at 106 East 60th Street in New York, with his cousin Louise Lawes (née Stiefelmeyer) and her husband Elliot Lawes. Kleibacker handled the publicity and business ends, and designer Charles Wetmore was hired as the designer. The business closed after a year and a half, and Kleibacker hired the Paris-trained technician at the head of the workroom, a talented Russian woman known as Madame Burg, to teach him the engineering aspects of design. This apprenticeship enabled him to design his own creations and produce them with Burg’s couture expertise. He then sold them to the exclusive Hattie Carnegie and Lord & Taylor stores.

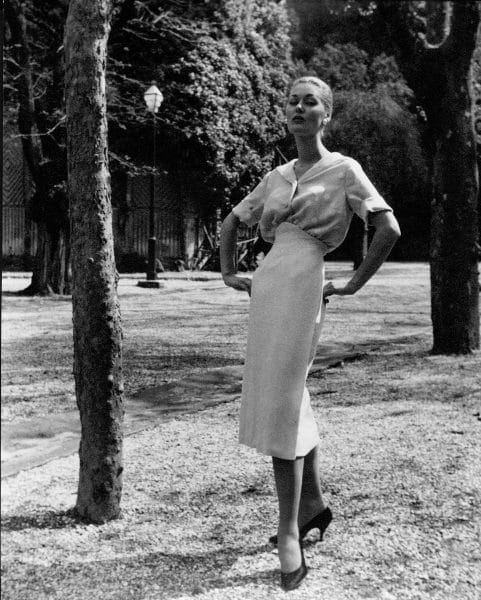

Chiffon Blouse and Wool Skirt, 1956

With a portfolio of his designs, he sailed for Paris in October 1954 and obtained a position as an assistant designer under Antonio Castillo at the couture house of Lanvin (December 1954-mid 1956). In 1957, he moved to Rome, where he entered into a short-lived venture called Antonelli-Kleibacker; that fall, he returned to New York and became a freelancer, working for such companies as Huntleigh Suits and Coats. In 1958, he was hired to work for famed fashion designer Nettie Rosenstein and began to experiment seriously with using the bias in designs. Two years later, with additional experience in draping and workroom operations, he left the company as it was phasing out its clothing department and went into business with one of Rosenstein’s head drapers, Edna Broglio, and by 1964 or 1965 was the sole owner of the company.

Chiffon Blouse and Wool Skirt, 1956

With a portfolio of his designs, he sailed for Paris in October 1954 and obtained a position as an assistant designer under Antonio Castillo at the couture house of Lanvin (December 1954-mid 1956). In 1957, he moved to Rome, where he entered into a short-lived venture called Antonelli-Kleibacker; that fall, he returned to New York and became a freelancer, working for such companies as Huntleigh Suits and Coats. In 1958, he was hired to work for famed fashion designer Nettie Rosenstein and began to experiment seriously with using the bias in designs. Two years later, with additional experience in draping and workroom operations, he left the company as it was phasing out its clothing department and went into business with one of Rosenstein’s head drapers, Edna Broglio, and by 1964 or 1965 was the sole owner of the company.

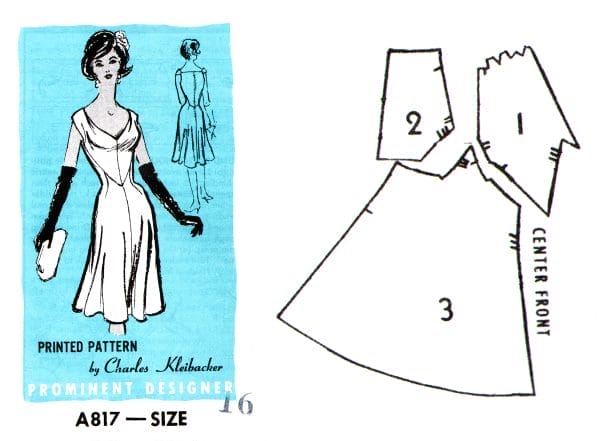

A817 Pattern, ca. 1960s

In 1960, Kleibacker established a studio at 26 West 76th Street in New York City. Called “Kleibacker,” it specialized in high-end exquisitely crafted ready-to-wear garments that accented body shape and enhanced comfort. This was mostly done through his masterful use of the bias, a direction of the cloth that forms a diagonal to the warp and weft grid of woven textiles. While drawing on the ability of the bias to cling to the body without hindering motion, he carefully engineered garments that did not attract unwanted attention to bodily flaws, and this won him a faithful following with time. A passionate man who worked tirelessly throughout his life, he aimed for perfection and maintained control of his product through his direct involvement in design, production, sales, public relations, fashion shows, and business matters. At the height of wholesale production, he supervised as many as 14 in-house employees. Unsatisfied with industrial construction methods that could not cater to the bias’s elasticity, he specialized in hand-sewn assembly techniques, many of which he developed. His complex designs limited his ability to expand the business, but Kleibacker has been one of the few Americans to have succeeded in the competitive world of fashion by creating intricate garments in the couture tradition.

A817 Pattern, ca. 1960s

In 1960, Kleibacker established a studio at 26 West 76th Street in New York City. Called “Kleibacker,” it specialized in high-end exquisitely crafted ready-to-wear garments that accented body shape and enhanced comfort. This was mostly done through his masterful use of the bias, a direction of the cloth that forms a diagonal to the warp and weft grid of woven textiles. While drawing on the ability of the bias to cling to the body without hindering motion, he carefully engineered garments that did not attract unwanted attention to bodily flaws, and this won him a faithful following with time. A passionate man who worked tirelessly throughout his life, he aimed for perfection and maintained control of his product through his direct involvement in design, production, sales, public relations, fashion shows, and business matters. At the height of wholesale production, he supervised as many as 14 in-house employees. Unsatisfied with industrial construction methods that could not cater to the bias’s elasticity, he specialized in hand-sewn assembly techniques, many of which he developed. His complex designs limited his ability to expand the business, but Kleibacker has been one of the few Americans to have succeeded in the competitive world of fashion by creating intricate garments in the couture tradition.

Blue Gazar Gown, 1977

In the early 1960s, his designs broke with the fashion trend of semi-fitted or non-fitted garments, focusing instead on fitted clothing that had more in common with the 1930s anatomically driven garments of designer Madeleine Vionnet. As the social unrest of the later 1960s embraced casual and sports attire, he endowed his garments with a fluidity proper to the four-ply silk crepe and fine silk jersey he preferred. Fabrics were the medium of Kleibacker’s art. He experimented with weave structures and tested his pattern pieces on the lengthwise or “straight” grain, the cross-grain, and all other varieties of diagonals, from the true bias (a 45° angle) to the many angles in between. The elasticity of the bias as well as the types of fabrics he selected added to the challenge and cost of production. By the early 1970s, the focus on soft, figure-flattering clothes cut on the bias again became fashionable. His designs and construction methods were sought-after, and his garments were sold in such luxury retailers as Bergdorf-Goodman and Neiman-Marcus. Acclaimed by the media, his client list included many famous names, including Patricia Nixon during her days as First Lady. Although some designers attempted to copy museum pieces from the 1930s, they generally lacked the knowledge needed to produce bias-cut garments. Although few enterprises at this time could support such uncompromising ideas, his work stood apart from that of others, and his design vocabulary was both modern and individualistic. Discerning customers recognized the timelessness and quality of his garments.

Blue Gazar Gown, 1977

In the early 1960s, his designs broke with the fashion trend of semi-fitted or non-fitted garments, focusing instead on fitted clothing that had more in common with the 1930s anatomically driven garments of designer Madeleine Vionnet. As the social unrest of the later 1960s embraced casual and sports attire, he endowed his garments with a fluidity proper to the four-ply silk crepe and fine silk jersey he preferred. Fabrics were the medium of Kleibacker’s art. He experimented with weave structures and tested his pattern pieces on the lengthwise or “straight” grain, the cross-grain, and all other varieties of diagonals, from the true bias (a 45° angle) to the many angles in between. The elasticity of the bias as well as the types of fabrics he selected added to the challenge and cost of production. By the early 1970s, the focus on soft, figure-flattering clothes cut on the bias again became fashionable. His designs and construction methods were sought-after, and his garments were sold in such luxury retailers as Bergdorf-Goodman and Neiman-Marcus. Acclaimed by the media, his client list included many famous names, including Patricia Nixon during her days as First Lady. Although some designers attempted to copy museum pieces from the 1930s, they generally lacked the knowledge needed to produce bias-cut garments. Although few enterprises at this time could support such uncompromising ideas, his work stood apart from that of others, and his design vocabulary was both modern and individualistic. Discerning customers recognized the timelessness and quality of his garments.

At the height of his fame in the 1960s to the mid 1970s, the marketing of garments to retailers began to shift. Kleibacker continued production in New York until 1984. During this time, he became progressively engaged in educational outreach throughout the United States. In fall 1984, he became a visiting professor at The Ohio State University, where by September 1985, he held a full-time designer-in-residence position and served as director and curator of the Historic Costume Collection until 1995. He continued to be sought after as a collector and guest curator for a number of institutions. In 2002, Kleibacker became an adjunct curator of design at the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio and served in that position until his death on January 3, 2010.

Examples of his work can be found at The Ohio State University (Columbus), Mount Mary University (Milwaukee), the Kent State University Museum and School of Fashion Design and Merchandising (Kent), the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology (New York) and the Alabama Department of Archives and History (Montgomery).