The Anniston Star

First published in 1912, the Anniston Star has developed a national reputation for independence, liberalism, and quality journalism throughout its history. Time magazine and other national journalistic publications have named it one of the best newspapers of any size. Its longstanding commitment to the liberal ideal of championing the rights of common people has drawn both praise and criticism from the public. Some Alabamians still refer to it as the “Red Star,” while others take great pride in its national reputation.

Anniston Star

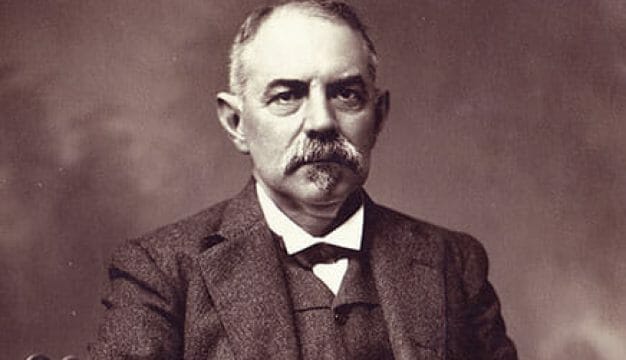

The Anniston Star traces its roots back to 1911, when Anniston native Harry Mell Ayers, managing editor for the afternoon Anniston Evening Star, left the paper and with local businessman and future governor Thomas E. Kilby purchased the morning daily, the Anniston Hot Blast. Within a year, Ayers had taken away enough circulation and advertising from the Evening Star to entice its owner, James B. Lloyd, to sell the paper to him; Ayers then merged the two papers. Although Ayers retained the Daily Hot Blast name on the masthead, Evening Star was given prominence and was clearly the preferred name. In 1914, after Kilby divested himself of his connections to the paper, the Star promoted his successful campaign for lieutenant governor and did so again when he ran for governor in 1917. The Evening Star joined with Kilby to champion the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which called for national Prohibition. Kilby then rewarded Ayers with an honorary appointment as a lieutenant colonel in the Alabama National Guard, and the young editor became known as “Colonel Ayers.”

Anniston Star

The Anniston Star traces its roots back to 1911, when Anniston native Harry Mell Ayers, managing editor for the afternoon Anniston Evening Star, left the paper and with local businessman and future governor Thomas E. Kilby purchased the morning daily, the Anniston Hot Blast. Within a year, Ayers had taken away enough circulation and advertising from the Evening Star to entice its owner, James B. Lloyd, to sell the paper to him; Ayers then merged the two papers. Although Ayers retained the Daily Hot Blast name on the masthead, Evening Star was given prominence and was clearly the preferred name. In 1914, after Kilby divested himself of his connections to the paper, the Star promoted his successful campaign for lieutenant governor and did so again when he ran for governor in 1917. The Evening Star joined with Kilby to champion the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which called for national Prohibition. Kilby then rewarded Ayers with an honorary appointment as a lieutenant colonel in the Alabama National Guard, and the young editor became known as “Colonel Ayers.”

Ayers was a leader in both journalism and civic organizations, including the Alabama Press Association, the Southern Newspapers Press Association, and the American Society of Newspaper Editors, as well as the Chamber of Commerce, Rotary, and the American Legion. In addition to reflecting his civic-mindedness, such affiliations also helped to increase the influence of the paper and its editorials.

Anniston Star Campus

Ayers’s Sunday editorials were a well-written mix of teaching, preaching, and counseling on local, regional, national, and international issues. His writing style was so distinct that some referred to his Sunday commentary as the “Colonel’s page.” Ayers urged readers to buy local products, counseled farmers to diversify crops, chided political adversaries, prodded politicians to build roads and schools, and explained complex international issues. His best editorials were sent to other editors throughout the South and later throughout the country, and many were cited or reprinted in metropolitan dailies.

Anniston Star Campus

Ayers’s Sunday editorials were a well-written mix of teaching, preaching, and counseling on local, regional, national, and international issues. His writing style was so distinct that some referred to his Sunday commentary as the “Colonel’s page.” Ayers urged readers to buy local products, counseled farmers to diversify crops, chided political adversaries, prodded politicians to build roads and schools, and explained complex international issues. His best editorials were sent to other editors throughout the South and later throughout the country, and many were cited or reprinted in metropolitan dailies.

The paper’s Progressive views on race and education became apparent early on. According to Ayers, moral and educated men, both black and white, could contribute to the community, and the South’s economic progress depended upon raising the standards of its black population. Although later labeled by critics as crusaders, Ayers and the journalistic staff of the Anniston Star more accurately worked as typical journalists, agitating when necessary, while advocating on behalf of the common good. National and international news events were interpreted in terms of how they affected the local community. In a 1938 speech to the SNPA, Ayers noted that too many publishers relied on their social and business contacts for determining editorial policies, instead of obtaining their information from reporters, who have closer contact with the public.

Although Ayers’s views occasionally antagonized people in the community, most of the populace still liked and respected him. In 1928, the Star stunned its Prohibition allies by backing Democratic nominee and Prohibition opponent Al Smith for president. In 1932, the paper supported Franklin D. Roosevelt for president and, unlike many of the South’s other progressive dailies, remained a strong supporter of the New Deal and FDR throughout his four terms as president. By 1939, the Star was receiving accolades from its journalistic peers, who praised Ayers’s uncompromising work.

With onset of World War II and the growth of nearby U.S. Army post Fort McClellan, Anniston and the Star prospered. Circulation doubled to 15,000 by the 1940s. Ayers travelled through the state promoting U.S. involvement in the war. He also befriended prominent journalists and politicians, sending them his editorials and inviting them to visit Anniston and the Star offices. The Star began to gain recognition in national publications for its forward-thinking approach to solving race problems. Editorials advocating judicial, educational, and voting rights for blacks were reprinted throughout the South.

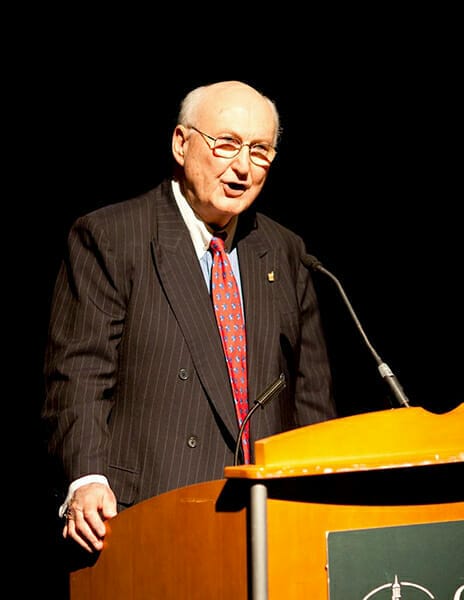

H. Brandt “Brandy” Ayers

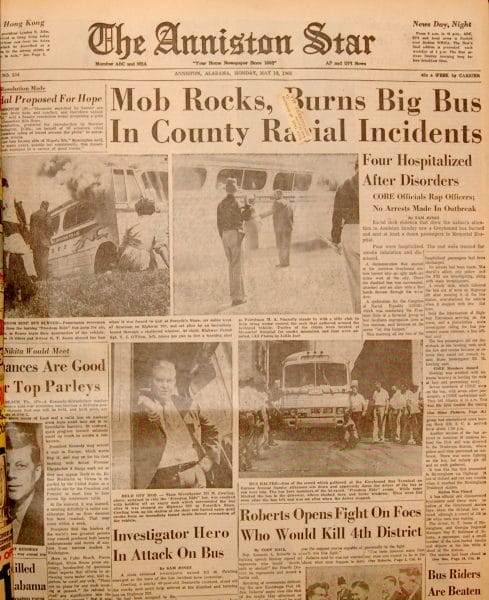

In 1948, Ayers defied the Dixiecrats, states’ rights southern Democrats who had broken with the national party, and promoted Harry Truman for president. In the 1950s, the Star condemned Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anticommunism hearings but retrenched on racial progress, opposing integration and discouraging the aims of the civil rights movement. The paper’s editorial policies returned to their more progressive roots in the 1960s when Harry Ayers’s son, H. Brandt Ayers, became the paper’s editor. In 1965, the Star denounced the Ku Klux Klan and ran a front-page editorial advocating rationality and communication in race relations. In 1972, H. Brandt Ayers followed his father Harry’s example and endorsed Sen. George McGovern for president despite the community’s strong support for Pres. Richard M. Nixon.

H. Brandt “Brandy” Ayers

In 1948, Ayers defied the Dixiecrats, states’ rights southern Democrats who had broken with the national party, and promoted Harry Truman for president. In the 1950s, the Star condemned Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anticommunism hearings but retrenched on racial progress, opposing integration and discouraging the aims of the civil rights movement. The paper’s editorial policies returned to their more progressive roots in the 1960s when Harry Ayers’s son, H. Brandt Ayers, became the paper’s editor. In 1965, the Star denounced the Ku Klux Klan and ran a front-page editorial advocating rationality and communication in race relations. In 1972, H. Brandt Ayers followed his father Harry’s example and endorsed Sen. George McGovern for president despite the community’s strong support for Pres. Richard M. Nixon.

Over the course of the following 30 years, the Star‘s editorial page steered a moderate to liberal course while the paper’s news coverage won state and national awards. Its national reputation helped it recruit reporters from Ivy League schools who, despite their youth, produced award-winning stories. The paper also cultivated local talent, hiring a college dropout named Rick Bragg and helping him launch a journalistic career that includes a Pulitzer Prize and a stint at the New York Times.

Having good reporters and editors has been a hallmark of the Star, and the paper today continues to serve as a training ground for young reporters while at the same time attracting and retaining highly regarded editors from more prominent metropolitan newspapers. A big contributor to the paper’s success from the 1920s into the early 1990s was Ralph Callahan, who began as a high school sports reporter and then rose through the ranks to become the paper’s business manager.

Anniston Star Press

In December 2002, Anniston Star publisher H. Brandt Ayers created the nonprofit Ayers Family Institute for Community Journalism in an effort to maintain the funds needed to keep the 28,000-circulation paper independent. The foundation is slated to receive all the family-owned stock of the Consolidated Publishing Company, which publishes the Star and three smaller papers. In partnership with the University of Alabama and with funding from the Knight Foundation, the institute launched a master’s program in community journalism and accepted its first students in autumn 2006.

Anniston Star Press

In December 2002, Anniston Star publisher H. Brandt Ayers created the nonprofit Ayers Family Institute for Community Journalism in an effort to maintain the funds needed to keep the 28,000-circulation paper independent. The foundation is slated to receive all the family-owned stock of the Consolidated Publishing Company, which publishes the Star and three smaller papers. In partnership with the University of Alabama and with funding from the Knight Foundation, the institute launched a master’s program in community journalism and accepted its first students in autumn 2006.

With its recent move from family ownership to nonprofit foundation, the Star hopes to maintain its independence while at the same time training a new generation of journalists willing to work for a paper that, as Bragg recalled, still heeded “Colonel” Ayers’s commitment to serve as the spokesperson for those whose voices seldom are heard.

Addition Resources

Ayers, Brandt. “Loving and Cussing: The Family Newspaper.” Nieman Reports 55 (June 2001): 56.

Barringer, Felicity. “Alabama Paper Plans to Go Nonprofit.” New York Times, 16 December 2002, A25.

Bragg, Rick. All Over But the Shouting. New York: Pantheon Books, 1997.

Cox, Liz. “A ‘Learning Newspaper’: In Anniston, A Big Plan to Stay Small.” Columbia Journalism Review 42 (May/June 2003): 16-18.

Stoker, Kevin. New South Community Journalism in the Age of Reform. Ph.D diss., University of Alabama, 1998.

———. “Liberal Journalism in the Deep South: Harry M. Ayers and The ‘Bothersome’ Race Question.” Journalism History 27 (1): 22-34.