Alabama Education Association

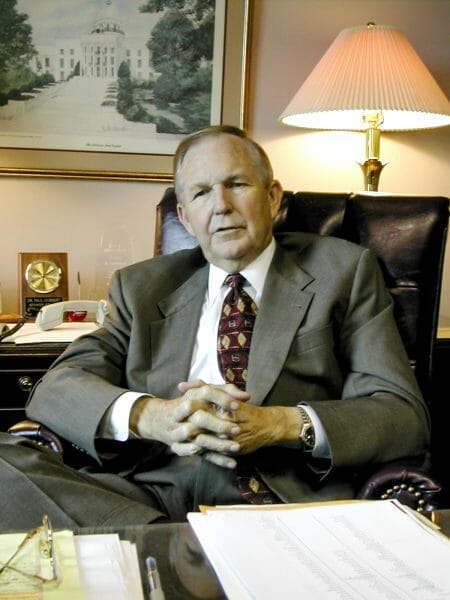

Founded in 1856 in Selma, the Alabama Education Association (AEA) is an interest group that represents public education employees in Alabama. Since the 1970s, AEA has been one of the most formidable interest groups in Alabama state politics. Its longtime executive secretary, Paul Hubbert (1935-2014), who led the organization from 1969 until 2011, was often characterized as the “real governor” of Alabama for his ability to deliver pay raises, health-care benefits, and a generous pension program for Alabama’s public education system personnel. The AEA’s influence has waned to some extent since the 2010 election, however, when a Republican supermajority took control of both houses of the Alabama Legislature.

Paul Hubbert

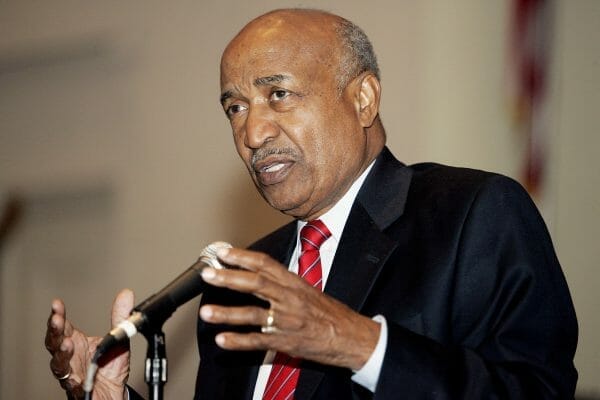

In its early incarnation, AEA was controlled by local school administrators and functioned primarily to reinforce the status quo as school superintendents drove its policies more than teachers and other education employees. The transformative event in AEA’s history was its merger in 1969 with the black teachers’ organization, the Alabama State Teachers Association (ASTA). With the addition of 10,000 ASTA members, AEA became an organization with approximately 30,000 members. Though this number was impressive, more importantly, the merger brought together white and black school personnel in a united organization with two young leaders who were knowledgeable about the political process. Hubbert, formerly superintendent of the city schools in Troy, Pike County, was hired only months before the merger, whereas ASTA executive director Joe Reed had already served two years with ASTA. Together, they forged a partnership that continued until their mutual retirement in 2011. In the new organization, Reed became AEA’s associate executive secretary. Within a relatively short time, AEA oriented itself to serving primarily the largest portion of its membership, teachers and support personnel, rather than the administrators who had dominated the organization in earlier years.

Paul Hubbert

In its early incarnation, AEA was controlled by local school administrators and functioned primarily to reinforce the status quo as school superintendents drove its policies more than teachers and other education employees. The transformative event in AEA’s history was its merger in 1969 with the black teachers’ organization, the Alabama State Teachers Association (ASTA). With the addition of 10,000 ASTA members, AEA became an organization with approximately 30,000 members. Though this number was impressive, more importantly, the merger brought together white and black school personnel in a united organization with two young leaders who were knowledgeable about the political process. Hubbert, formerly superintendent of the city schools in Troy, Pike County, was hired only months before the merger, whereas ASTA executive director Joe Reed had already served two years with ASTA. Together, they forged a partnership that continued until their mutual retirement in 2011. In the new organization, Reed became AEA’s associate executive secretary. Within a relatively short time, AEA oriented itself to serving primarily the largest portion of its membership, teachers and support personnel, rather than the administrators who had dominated the organization in earlier years.

Hubbert and Reed earned the confidence of AEA members early on when they resisted powerful governor George Wallace in his attempt to divert funds from the Teachers Retirement System (TRS) of Alabama and the Education Trust Fund (ETF) in 1971 to pay for improvements in the state’s substandard mental health system. During this period, the governor in effect appointed the leadership of the House of Representatives, including its floor leaders and the chair of the powerful Ways and Means Committee. Despite Wallace’s seeming near total control of the decision-making process in the body, he was defeated in his efforts to divert these funds by a massive grassroots effort orchestrated by AEA. Whereas it appeared at the beginning of the conflict that Wallace would prevail, a different outcome engineered by Hubbert and Reed ingratiated them with AEA rank and file members.

Joe Reed

The Education Trust Fund has grown at a much higher rate than the General Fund, which funds most of the rest of the state government. Yet, for many years, no serious effort has been made to divert monies from traditional sources of education funding for other purposes because AEA defeated Wallace’s efforts at a time when he was at the peak of his political influence. From time to time, state newspapers editorialize about Alabama having the largest percentage of tax revenues earmarked for specific programs and making the case for doing away with the practice to provide Alabama lawmakers the flexibility to address needs in a timely fashion. But bills introduced to alter the earmarking process have remained buried in committee with little chance of floor action and a likelihood of passage because of AEA’s lobbying strength, even in an era of a Republican legislative supermajority.

Joe Reed

The Education Trust Fund has grown at a much higher rate than the General Fund, which funds most of the rest of the state government. Yet, for many years, no serious effort has been made to divert monies from traditional sources of education funding for other purposes because AEA defeated Wallace’s efforts at a time when he was at the peak of his political influence. From time to time, state newspapers editorialize about Alabama having the largest percentage of tax revenues earmarked for specific programs and making the case for doing away with the practice to provide Alabama lawmakers the flexibility to address needs in a timely fashion. But bills introduced to alter the earmarking process have remained buried in committee with little chance of floor action and a likelihood of passage because of AEA’s lobbying strength, even in an era of a Republican legislative supermajority.

Another key factor of AEA’s development into an influential organization is that it has done an outstanding job of expanding its membership. Whereas 30,000 was an impressive membership total in 1969, AEA continued to grow its membership such that it exceeded 100,000 members by around 2010. Toward the end of that decade, AEA stopped revealing its total membership, which suggests a decline from its peak of a decade ago. But even with reduced membership, it is still one of Alabama’s largest membership associations and commits a large portion of its human and financial resources to influencing Alabama’s public policy process. The size of AEA indicates the confidence that teachers and other school personnel have in the organization to represent their interests. The overall membership numbers are impressive as AEA members cannot be members of AEA alone, but also must join the National Education Association (NEA) to be a member in good standing with AEA. Thus, AEA is probably one of the leading state education associations in the nation in terms of representing teachers without union representation, which is the case for many states outside the South.

The impressive membership totals translate into a substantial organizational budget that allows AEA to hire and retain an experienced staff, which plays a key role in achieving its objectives. AEA does not reveal its annual operating budget, but its financial resources fund a large staff that works in a three-story building near Capitol Hill in Montgomery. Whereas only a portion of the staff works actively in the political arena, their numbers and their experience are indicators of AEA’s viability in the political arena over a long period of time.

As with most interest groups with an active public policy agenda, AEA has an affiliated political action committee, A-Vote, that enables AEA to be one of the largest electoral campaign contributors in Alabama. From 2002 through 2007, AEA reports submitted to the Alabama Secretary of State indicate that it contributed more than $9.6 million to political campaigns. Traditionally, AEA provided a far larger portion of A-Vote funds to Democratic Party candidates for legislative office than for Republican legislative candidates. Such a contribution pattern was to be expected as the Democrats controlled both houses of the Alabama Legislature with substantial majorities.

Since a disastrous 2014 election cycle in which AEA contributed approximately $12 million and only seven candidates it supported were able to win or keep a legislative seat, AEA has accepted that Republicans are in full control of the Alabama Legislature and has shifted more and more of its A-Vote funds to Republican candidates. With most legislative seats firmly in control of the Republican Party, AEA has strategically funneled contributions into Republican primary contests to attempt to influence the election of legislators who are more likely to be disposed to supporting its public policy agenda. For the 2018 election cycle, approximately 60 percent of AEA campaign contributions went to Republicans, many of whom will assume key positions of leadership beginning in 2019 for the legislative quadrennium. Having financially assisted a large number of Republican office holders in the 2018 elections, AEA has likely ensured access to the legislative process at a level that it has not experienced for eight years, since the Republican Party gained supermajority status in both legislative chambers. The access and influence will not likely approach that of Hubbert and Reed in their heyday of power, but AEA should regain its position as a significant power player in the legislative process.

Until the 2011 session, AEA was able to win most of its legislative battles. Since that time, AEA has been on the defensive and has suffered defeats that were unthinkable a few short years ago, when legislators loyal to the organization were easily able to defend its turf. Among the “new order” policies and programs that AEA has had to accept are authorization for the establishment of charter schools, new rules that make for less generous retirement benefits for teachers and support personnel, the end of the Deferred Retirement Option Program (DROP), and the enactment of the Alabama Accountability Act. The latter is a bitter pill for public school advocates as this program, whose stated intention is to help students attending “failing schools,” has resulted in approximately $140 million fewer dollars being invested in Alabama’s public schools in favor of private school scholarships.

Finally, AEA’s largest challenge has been its inability to transition to long-term, effective leadership since the retirements of Paul Hubbert and Joe Reed. Since 2011, the organization has had three short-term leaders, with its most recent executive secretary having resigned in October 2018 to take a comparable position in Virginia. As was the case at the end of the Hubbert/Reed era, AEA’s future influence will be associated with its ability to transition to new, effective leadership.