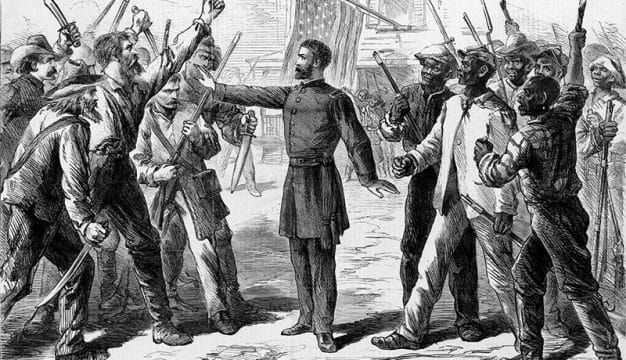

David P. Lewis (1872-74)

David P. Lewis, 1872

David P. Lewis (ca. 1820-1884) was Alabama’s governor from 1872-74. Lewis represented Alabama Unionists, who expected to lead the state in the post-Civil War era. The legislative turmoil over civil rights during his governorship foreshadowed state racial politics for the remainder of the nineteenth century.

David P. Lewis, 1872

David P. Lewis (ca. 1820-1884) was Alabama’s governor from 1872-74. Lewis represented Alabama Unionists, who expected to lead the state in the post-Civil War era. The legislative turmoil over civil rights during his governorship foreshadowed state racial politics for the remainder of the nineteenth century.

David Peter Lewis was born circa 1820 in Charlotte County, Virginia, the son of Mary Smith Buster and Peter C. Lewis, a plantation owner. The family moved in the 1820s to north Alabama’s Madison County, where Peter Lewis became a county commissioner. David Lewis studied law in Huntsville and also attended lectures in law at the University of Virginia. He was admitted to the Alabama State Bar and moved to Lawrence County in northwest Alabama in 1843, where he practiced law. He never married. By 1860 Lewis owned $20,000 in real property and $40,185 in personal property, including 34 enslaved workers.

In the 1860 presidential race, Lewis supported Democratic candidate Stephen A. Douglas and represented Lawrence County in the 1861 Alabama constitutional convention. He voted against secession but signed the ordnance after it passed in the convention, under instructions from his constituents. In 1861 he was elected to the Provisional Confederate Congress but resigned in April and joined a volunteer company that soon disbanded. Lewis declined an appointment as a lieutenant colonel in Confederate colonel Philip Roddey’s command.

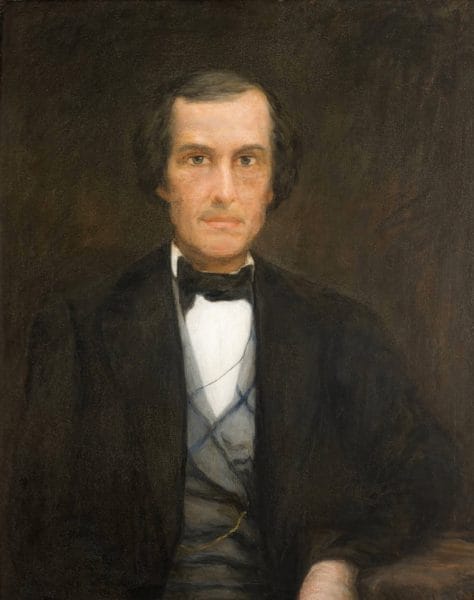

Thomas Hill Watts

In 1862 Lewis and other north Alabama Unionists organized the secret Peace Society, and in 1863 Alabama voters chose a legislature and a governor, Thomas Hill Watts, who supported peace. Lewis was appointed judge of the fourth Alabama judicial circuit in 1863 but resigned in January 1864. Although exempt from conscription as the owner of a public mill, he was ordered to report for military service in the fall of 1864. He refused and crossed through federal lines to Nashville, remaining there until the Civil War ended.

Thomas Hill Watts

In 1862 Lewis and other north Alabama Unionists organized the secret Peace Society, and in 1863 Alabama voters chose a legislature and a governor, Thomas Hill Watts, who supported peace. Lewis was appointed judge of the fourth Alabama judicial circuit in 1863 but resigned in January 1864. Although exempt from conscription as the owner of a public mill, he was ordered to report for military service in the fall of 1864. He refused and crossed through federal lines to Nashville, remaining there until the Civil War ended.

Lewis returned to Alabama in July 1865 to practice law in Huntsville. Pres. Andrew Johnson recently had announced a plan of Reconstruction for the former Confederate states. As a former member of the Provisional Confederate Congress and owner of property valued at $20,000 in 1860, Lewis was disfranchised. He applied for a pardon, was certified as a registered voter, and quietly practiced law. With the passage of the Reconstruction Acts in March 1867, control of Reconstruction passed to the U.S. Congress. Lewis returned to politics in 1868 as a delegate to the National Democratic Convention. After Republicans swept the 1868 national elections, Lewis re-evaluated his political allegiances and in 1869 joined the Republican Party.

In many southern states, newcomers to the South (known as carpetbaggers) controlled Congressional Reconstruction. In Alabama, however, southern white Republicans (known as scalawags) outnumbered newcomers and newly enfranchised blacks and dominated Republican politics in Alabama. Despite this success Lewis was livid because he believed that Unionists merited greater reward under Congressional Reconstruction for their opposition to secession in 1861. Particularly offensive was the denial of office-holding ability stipulated in the Fourteenth Amendment, whereby men who had sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution and subsequently sided with the Confederacy could not hold office until pardoned by Congress. Lewis was outraged that a man who had “sincerely grieved at the success of secession, and whose only crime was a fatherly sympathy for his son, who joined the rebel army to avoid the disgrace of conscription” was viewed to be as guilty as a man who had conceived the idea of secession.

Having lost the Alabama governorship in 1870, Republicans realized that their success hinged on the support of prewar Unionists. Republicans proposed a state ticket entirely of native Unionists. As a prominent Unionist by 1872, Lewis was an attractive gubernatorial candidate, and he was elected decisively over the Democratic nominee. But both political parties claimed control of the legislature and organized separately in November 1872: Democrats in the state capitol and Republicans in the federal courthouse. Governor Lewis recognized the courthouse legislature and asked the federal government for assistance.

The U.S. attorney general directed Lewis to allow both legislatures to meet temporarily and then merged the two groups into one in December 1872. Republicans held a majority of two in the House and Democrats a majority of one in the Senate after the death of a Republican senator in early 1873. After this reorganization the work of the courthouse legislature was legalized. The almost equal division of the legislature between parties paralyzed legislative action. The Panic of 1873 wreaked economic havoc in the state, and Lewis was blamed for the state’s condition of near bankruptcy by 1874. The damage had been done between 1868 and 1872, however, when first a Republican and then a Democratic government appropriated the state’s credit to construct railroads.

The most important issue considered during Lewis’s administration was civil rights. When the house judiciary committee did not act on a proposed bill, black representatives forced committee action. The bill was not reported favorably, and the committee favored a milder substitute bill. After a stormy debate the bill died. The Democrat-controlled Senate introduced a bill similar to the House bill, and the Senate eventually passed a substitute bill, but the legislature adjourned before the House acted on the Senate bill.

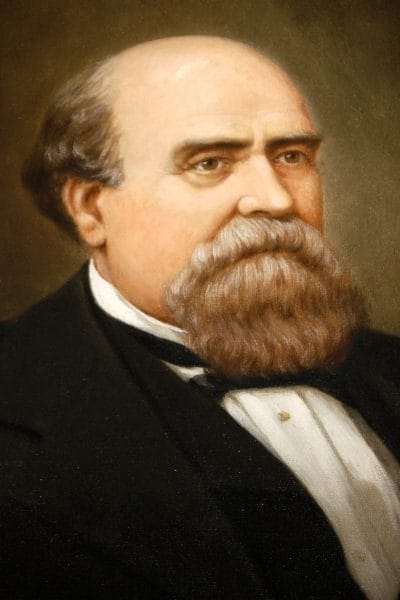

George S. Houston

The acrimonious debate publicly exposed the Republican dilemma on civil rights: endorse any civil rights bill and alienate north Alabama whites; oppose any civil rights bill and alienate blacks. Republicans were forced to explain how a Republican-controlled House had defeated a civil rights bills when a Democratic-controlled Senate had passed one. Thus Republican success in Alabama hinged on how well the party could play both white ends of the state against the black middle. The race issue had the potential to destroy the Republican Party in Alabama, but Lewis remained aloof and silent throughout the legislative uproar.

George S. Houston

The acrimonious debate publicly exposed the Republican dilemma on civil rights: endorse any civil rights bill and alienate north Alabama whites; oppose any civil rights bill and alienate blacks. Republicans were forced to explain how a Republican-controlled House had defeated a civil rights bills when a Democratic-controlled Senate had passed one. Thus Republican success in Alabama hinged on how well the party could play both white ends of the state against the black middle. The race issue had the potential to destroy the Republican Party in Alabama, but Lewis remained aloof and silent throughout the legislative uproar.

In 1874 Alabama Republicans nominated Lewis for a second term, but the conflicts over civil rights and party patronage continued. Also, Congress had begun debate over a federal civil rights bill. Alabama Democrats made race the central issue of the 1874 campaign and inflamed voters. Democratic candidate George S. Houston won the governor’s race, and Democrats won the legislature in a landslide. Lewis failed to secure a position as a federal district judge and retired from politics to his home in Huntsville. When Democrats rewrote the Alabama constitution in 1875, he endorsed ratification of the document. By fall 1876 Lewis, like other disillusioned Alabama scalawags, had quietly returned to the Democratic Party and to practicing law. He died on July 3, 1884, and was buried in Maple Hill Cemetery in Huntsville.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk. The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865-1881. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1977.

- Wiggins, Sarah Van V. “Amnesty and Pardon and Republicanism in Alabama.” Alabama Historical Quarterly 26 (1964): 240-48.