Erik Overbey

Erik Overbey

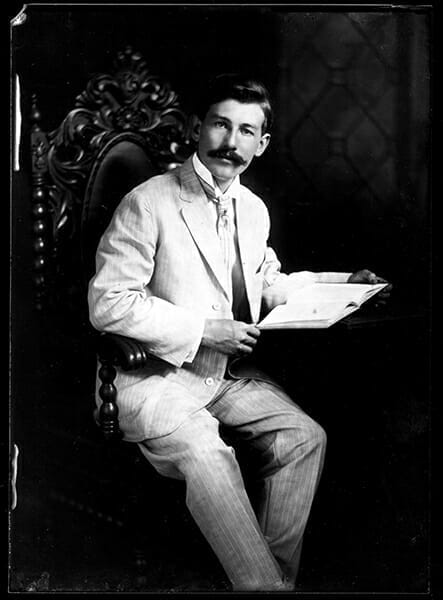

An immigrant from Norway, Erik Overbey (1882-1977) photographed the people and places in his adopted home of Mobile, Mobile County, for more than 50 years and produced a lasting record of life in Alabama’s port city. He was the city’s preeminent photographer from World War I until his retirement in 1957. His work is now publicly held at the University of South Alabama, and Mobile is one of a very few communities in the United States to have such extensive photographic documentation of its heritage.

Erik Overbey

An immigrant from Norway, Erik Overbey (1882-1977) photographed the people and places in his adopted home of Mobile, Mobile County, for more than 50 years and produced a lasting record of life in Alabama’s port city. He was the city’s preeminent photographer from World War I until his retirement in 1957. His work is now publicly held at the University of South Alabama, and Mobile is one of a very few communities in the United States to have such extensive photographic documentation of its heritage.

Erik Pederson Overboe was born in the town of Hafslo, Norway, on February 12, 1882, and as a young man learned the tailor’s trade. He came to America in 1901 and shortly thereafter apprenticed to John J. Tvedt, a tailor who owned the Metropolitian Dye Works in Mobile. Perhaps to make it easier for Americans to pronounce, he changed his surname to Overbey in 1905. Around 1906, Overbey left tailoring and joined fellow Norwegian P. E. Johnson, who had some photographic experience, in opening Johnson and Overbey Photographers.

Big Fish

The young immigrant found that his partner knew little about photography, however, so he had to teach himself, even as he learned the language and customs of his new home. He also acquired a large collection of glass-plate negatives belonging to Canadian photographer W. A. Reed to make money selling reprints. In 1907, the Mobile directory listed an entry for simply Overbey Studio, and by all accounts Overbey thrived in his new profession. Utterly devoted to his craft, Overbey routinely put in long days and often nights as his business expanded. Though somewhat taciturn, Overbey was affable and well liked and had good relations with other photographers in the city throughout his life. His primary business was portraiture, but he also took pictures on commission for shipyards and other industrial establishments and sold images to the Mobile Register during the 1920s and 1930s. Throughout his long career, he continued to use the large-format cameras on which he first had learned photography.

Big Fish

The young immigrant found that his partner knew little about photography, however, so he had to teach himself, even as he learned the language and customs of his new home. He also acquired a large collection of glass-plate negatives belonging to Canadian photographer W. A. Reed to make money selling reprints. In 1907, the Mobile directory listed an entry for simply Overbey Studio, and by all accounts Overbey thrived in his new profession. Utterly devoted to his craft, Overbey routinely put in long days and often nights as his business expanded. Though somewhat taciturn, Overbey was affable and well liked and had good relations with other photographers in the city throughout his life. His primary business was portraiture, but he also took pictures on commission for shipyards and other industrial establishments and sold images to the Mobile Register during the 1920s and 1930s. Throughout his long career, he continued to use the large-format cameras on which he first had learned photography.

Dauphin Street, ca. 1922

Within a decade of opening his studio, the young Norwegian was the city’s premier photographer. He remained in his upstairs studio on Dauphin Street in the heart of Mobile, however, and displayed his photographs in a case by the sidewalk entrance. Passersby were treated to images of parades and presidents, well-known Mobilians, and industrial and waterfront activity—all designed to attract more business. Overbey did almost all his own camera and darkroom work, hiring assistants only as needed. In 1915, he joined the year-old Rotary Club of Mobile and was an active member until he retired and a dues-paying member all his life. He married Ida Cornelia Schiemann, a Mobile native, and the couple had three children. Ida died in 1944.

Dauphin Street, ca. 1922

Within a decade of opening his studio, the young Norwegian was the city’s premier photographer. He remained in his upstairs studio on Dauphin Street in the heart of Mobile, however, and displayed his photographs in a case by the sidewalk entrance. Passersby were treated to images of parades and presidents, well-known Mobilians, and industrial and waterfront activity—all designed to attract more business. Overbey did almost all his own camera and darkroom work, hiring assistants only as needed. In 1915, he joined the year-old Rotary Club of Mobile and was an active member until he retired and a dues-paying member all his life. He married Ida Cornelia Schiemann, a Mobile native, and the couple had three children. Ida died in 1944.

Old Stove Round Up

By the 1950s, Overbey was unquestionably Mobile’s most famous photographer. In the mid-1950s, he developed cataracts and had difficulty using his old-fashioned view cameras after eye surgery. He retired in 1957 and sold his business to Frances White, who had worked for him for many years. She operated the studio for another five years and then closed the studio’s doors permanently. Overbey had left her his negatives and those of W. A. Reed, and White sold them to the Mobile Public Library in 1965 for $5,000. The staff worked for more than a year to process and conserve the 100,000 glass and film negatives. In 1978, the Mobile Public Library arranged to transfer the collection to the University of South Alabama (USA), which was better able to manage the large collection. The negatives are now housed in the USA archives. Sometime in the late 1960s, Overbey left Mobile and thereafter lived with his daughter and her family in the Carolinas and then Virginia. But he kept up with his collections and was delighted with their move to USA. He died on September 2, 1977, at the age of 96.

Old Stove Round Up

By the 1950s, Overbey was unquestionably Mobile’s most famous photographer. In the mid-1950s, he developed cataracts and had difficulty using his old-fashioned view cameras after eye surgery. He retired in 1957 and sold his business to Frances White, who had worked for him for many years. She operated the studio for another five years and then closed the studio’s doors permanently. Overbey had left her his negatives and those of W. A. Reed, and White sold them to the Mobile Public Library in 1965 for $5,000. The staff worked for more than a year to process and conserve the 100,000 glass and film negatives. In 1978, the Mobile Public Library arranged to transfer the collection to the University of South Alabama (USA), which was better able to manage the large collection. The negatives are now housed in the USA archives. Sometime in the late 1960s, Overbey left Mobile and thereafter lived with his daughter and her family in the Carolinas and then Virginia. But he kept up with his collections and was delighted with their move to USA. He died on September 2, 1977, at the age of 96.

Erik Overbey made a unique and invaluable contribution to his adopted city. His photographs of downtown streets have proven priceless for historic preservation. Other images document the everyday life of Mobile: ships and sailors, workers of all sorts, machines and industry at work, Mardi Gras and its festivities, church activities, weddings, natural and human-made disasters, and more. His pictures are on display all over the city and have been used innumerable times in books and magazines. His work is so important and so much appreciated that a century after he opened his photographic studio he still is probably the city’s best known photographer, and his fame has spread far beyond the town he knew and loved.

Additional Resources

Melton, Alonza McLaurin, and Michael Thomason. The Image of Progress: Alabama Photographs, 1872–1917. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1980.

Robb, Frances Osborn. Shot in Alabama: A History of Photography, 1839-1941, and a List of Photographs. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2016.

Thomason, Michael. Trying Times: Alabama Photographs, 1917–1945. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985.