Holland Smith

Alabama native Holland McTyeire Smith (1882-1967) was a U.S. Marine Corps officer whose career spanned more than four decades and who served in two world wars. Smith was a controversial commander who often clashed with his U.S. Navy and U.S. Army counterparts. A tireless advocate for the advancement of the Marine Corps, Smith was instrumental in developing the amphibious landing tactics used by both the Army and Marines during World War II. As the senior Marine Corps officer in the Pacific Theater of Operations, he exercised varying levels of command authority in numerous campaigns.

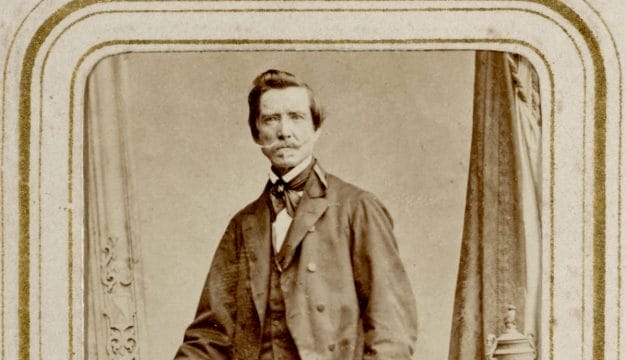

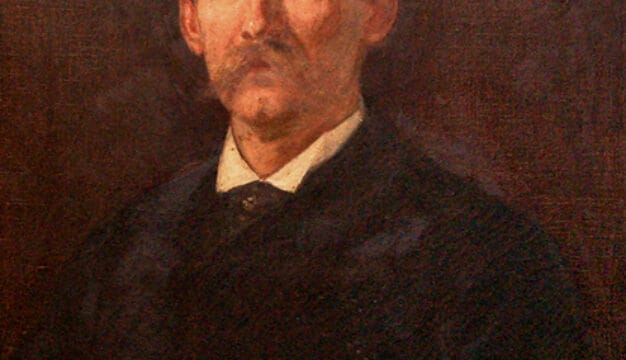

Holland McTyeire Smith

Smith was born on April 20, 1882, in Hatchechubbee, Russell County, to John Wesley Smith Jr. and Cornelia Caroline McTyeire Smith. He had one sibling, a younger sister. His father John Jr. later changed his middle initial to “V” to avoid being confused with his father. John Smith practiced law in Montgomery, served in the state legislature, was Court Solicitor for the state of Alabama, and was president of the Alabama Railway Commission. When Holland was three, his parents moved the family to nearby Seale, where Holland would spend the majority of his formative years. After ten years attending the same small schoolhouse, Smith entered Alabama Polytechnic Institute (API; present-day Auburn University) at Auburn, Lee County, in 1898. There, Smith received his first taste of military training, which at that time was mandatory for all male students. At API, Smith excelled at track and history, enjoying books about French military and political leader Napoleon Bonaparte. After graduating from API, Smith earned a law degree from the University of Alabama. He also joined the Alabama National Guard, where he developed interest in military life. He spent a short time practicing law with his father in Montgomery but found that he disliked the profession and decided to pursue a career in the military.

Holland McTyeire Smith

Smith was born on April 20, 1882, in Hatchechubbee, Russell County, to John Wesley Smith Jr. and Cornelia Caroline McTyeire Smith. He had one sibling, a younger sister. His father John Jr. later changed his middle initial to “V” to avoid being confused with his father. John Smith practiced law in Montgomery, served in the state legislature, was Court Solicitor for the state of Alabama, and was president of the Alabama Railway Commission. When Holland was three, his parents moved the family to nearby Seale, where Holland would spend the majority of his formative years. After ten years attending the same small schoolhouse, Smith entered Alabama Polytechnic Institute (API; present-day Auburn University) at Auburn, Lee County, in 1898. There, Smith received his first taste of military training, which at that time was mandatory for all male students. At API, Smith excelled at track and history, enjoying books about French military and political leader Napoleon Bonaparte. After graduating from API, Smith earned a law degree from the University of Alabama. He also joined the Alabama National Guard, where he developed interest in military life. He spent a short time practicing law with his father in Montgomery but found that he disliked the profession and decided to pursue a career in the military.

Smith was unsuccessful in securing a commission in the U.S. Army, but with the assistance of Alabama congressman Ariosto A. Wiley, he received a commission as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps on March 28, 1905, at the age of 21. He spent a year undergoing additional Marine officer training at the School of Application in Annapolis, Maryland, which is known today as the Basic School and located in Quantico, Virginia. After completing his training, he was deployed in 1906 to the Philippines. There, Smith took command of A Company of the Second Marine Regiment. Among its other duties, Smith’s unit was tasked with building up the defenses of the Bataan Peninsula. Because of his hard-driving command style and occasional profane outbursts, Smith’s men gave him the nickname “Howlin’ Mad,” a nickname that would stick to Smith for the rest of his life.

Adm. Nimitz, Vice Adm. Spruance, and Major Gen. Smith

Smith contracted malaria in the Philippines and returned to the United States in 1908. A few months later, he married Ada Wilkinson, a young Pennsylvanian whom he had met in Annapolis. The couple would have one son, John V. Smith, who would rise to the rank of vice admiral in the Navy. After brief deployments in Nicaragua and Panama, Smith returned to the Philippines and then served as the commander of the Marines stationed on the USS Galveston. Upon returning to the United States in 1916, Smith, along with a detachment of Marines, were sent to the Dominican Republic during the U.S. occupation of that island nation. After order was restored, Smith was appointed as the Military Commander of Puerto Plata in the Philippines. While Smith was serving in this administrative position, the United States declared war on Germany, thus entering World War I. Smith and his unit were recalled to the United States and two months later were sailing for France.

Adm. Nimitz, Vice Adm. Spruance, and Major Gen. Smith

Smith contracted malaria in the Philippines and returned to the United States in 1908. A few months later, he married Ada Wilkinson, a young Pennsylvanian whom he had met in Annapolis. The couple would have one son, John V. Smith, who would rise to the rank of vice admiral in the Navy. After brief deployments in Nicaragua and Panama, Smith returned to the Philippines and then served as the commander of the Marines stationed on the USS Galveston. Upon returning to the United States in 1916, Smith, along with a detachment of Marines, were sent to the Dominican Republic during the U.S. occupation of that island nation. After order was restored, Smith was appointed as the Military Commander of Puerto Plata in the Philippines. While Smith was serving in this administrative position, the United States declared war on Germany, thus entering World War I. Smith and his unit were recalled to the United States and two months later were sailing for France.

Smith, the captain of a machine gun company, was first stationed at St. Nazaire, a harbor in western France, where his unit was ordered to assist with the unloading of supplies. Smith was promoted to major and dispatched to attend the Army General Staff College in Langres in the Champagne-Ardenne region near the front lines. Smith—who was one of only six Marines to complete this course—then was promoted to brigade adjutant in the Fourth Marine Brigade. Smith saw brief action at the Battle of Belleau Wood, in which a German offensive toward Paris was blunted, before being transferred to First Corps, First Army, to serve as a communications officer. In this position, Smith took part in several of the war’s final engagements, including the Second Battle of the Marne and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. After Germany surrendered, Smith served as an operations officer for the Third Army, but he was unhappy in this capacity and soon acquired permission to return to the United States. He finished World War I with the rank of major.

In the post-war period, Smith served in a variety of capacities. He was stationed at the Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia and then attended the Navy War College in Newport, Rhode Island. There, Smith clashed with many high-ranking Navy officers over the nature of amphibious warfare and the place of the Marine Corps within the U.S. armed services. Smith, along with other progressively minded Marine officers, envisioned the Marine Corps as the ideal service to perform the landings. More conservative naval officers, however, felt that the Marines were a secondary branch of the military and that the Army or Navy should perform the landings. Furthermore, they wrongly argued that the mere presence of a large fleet would result in the enemy abandoning its coastal positions, whereas Smith advocated for coordinated shore bombardment by the Navy to neutralize coastal defenses. Events during World War II would prove Smith correct on the need for revamped landing methods.

Smith gradually was able to influence his comrades and was appointed to the War Plans Division, where he continued to advocate reform. To provide Marines and soldiers with a venue to practice his techniques, Smith used two islands near Puerto Rico and later conducted training exercises at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Smith also advocated for technological innovations, insisting upon the development of ramp boats to provide landing forces with more flexibility in choosing landing sites. Shortly before the outbreak of war, the Higgins Boat, which met these specifications, was adopted by the Navy and was used in numerous island invasions in the Pacific and most notably in the June 6, 1944, D-Day landings in Normandy, France.

Adm. Chester Nimitz and Lt. Gen. Holland Smith

After U.S. entry into World War II, Smith, now a major general, continued to train Marine and Army units in amphibious landings. Despite his abilities as a trainer and administrator, Smith wanted a combat command. Finally in 1943, Adm. Chester Nimitz, the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, sent for Smith to join him in a tour of the South Pacific. After the tour, Smith was given command of the V Amphibious Corps. Much to Smith’s disappointment, however, his immediate superior, Adm. Kelly Turner, refused to allow him to make key decisions. Even though Smith was supposed to take command of an operation after the troops made it to the beaches, Turner insisted upon maintaining command on the ground. Consequently, Smith was forced into a restricted and often advisory role during the invasions of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands.

Adm. Chester Nimitz and Lt. Gen. Holland Smith

After U.S. entry into World War II, Smith, now a major general, continued to train Marine and Army units in amphibious landings. Despite his abilities as a trainer and administrator, Smith wanted a combat command. Finally in 1943, Adm. Chester Nimitz, the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, sent for Smith to join him in a tour of the South Pacific. After the tour, Smith was given command of the V Amphibious Corps. Much to Smith’s disappointment, however, his immediate superior, Adm. Kelly Turner, refused to allow him to make key decisions. Even though Smith was supposed to take command of an operation after the troops made it to the beaches, Turner insisted upon maintaining command on the ground. Consequently, Smith was forced into a restricted and often advisory role during the invasions of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands.

Smith would play a much larger role in his next operation. The victories in the Gilberts and Marshalls had opened the door for an assault on the Marianas. If the United States was able to occupy these islands, especially Saipan, its long-range bombers could reach Japan. Once again, Turner and Smith led the assault. This time, however, Smith commanded two Marine divisions and one Army division. The Japanese defenders of Saipan put up such resistance that Smith ordered his reserve unit, the Twenty-seventh Army Division, into battle on the second day. As Smith’s three divisions advanced northward up the island, the Army unit was unable to move as rapidly as the Marines. Smith, angry over the lack of progress, removed the Twenty-seventh’s commander, Gen. Ralph Smith. A Marine officer relieving an Army officer was an unprecedented event, and this episode proved to be the most controversial of Smith’s life. His decision was reviewed by Army general Simon Buckner Jr., who concluded that although Ralph Smith’s removal was unwarranted, Smith had the authority to do so. Nevertheless, this confrontation led Smith’s superiors to usher him into the background of the war effort.

Lt. Gen. Holland Smith and Col. Dudley Brown at Iwo Jima

After taking Saipan, Holland Smith was promoted to commander of the newly formed Fleet Marine Force and was headquartered in Hawaii, away from the front lines. Although nominally an advancement, the change in rank was actually was an effort to muzzle the confrontational general. Nevertheless, Navy commanders requested his assistance at the Battle of Iwo Jima, though his role there was largely supervisory. Smith returned to the United States in the summer of 1945. One year later, he retired at the rank of full general. During his retirement, spent in La Jolla, California, Smith wrote his controversial memoir, Coral and Brass, in which he reaffirmed his criticisms of the Army and Navy. Smith died in San Diego, California, on January 12, 1967, and was buried at nearby Fort Rosecrans Cemetery.

Lt. Gen. Holland Smith and Col. Dudley Brown at Iwo Jima

After taking Saipan, Holland Smith was promoted to commander of the newly formed Fleet Marine Force and was headquartered in Hawaii, away from the front lines. Although nominally an advancement, the change in rank was actually was an effort to muzzle the confrontational general. Nevertheless, Navy commanders requested his assistance at the Battle of Iwo Jima, though his role there was largely supervisory. Smith returned to the United States in the summer of 1945. One year later, he retired at the rank of full general. During his retirement, spent in La Jolla, California, Smith wrote his controversial memoir, Coral and Brass, in which he reaffirmed his criticisms of the Army and Navy. Smith died in San Diego, California, on January 12, 1967, and was buried at nearby Fort Rosecrans Cemetery.

Holland Smith’s greatest contributions to Allied victory during World War II were his innovations in amphibious landing tactics. Although he craved battlefield command, Smith was a more able trainer and administrator than he was field commander. Despite his combative personality, Smith played a significant role in the development and advancement of the Marine Corps during the first half of the twentieth century.

Additional Resources

Gailey, Harry A. “Howlin’ Mad” vs. the Army: Conflict and Command, Saipan 1944. Novato, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1986.

Leckie, Robert. Strong Men Armed: The United States Marines Against Japan. 1962. Reprint, Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press, 2010.

Smith, Holland M., and Percy Finch. Coral and Brass. 1947. Reprint, New York: Bantam Books, 1987.

Spector, Ronald H. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan. New York: Free Press, 1985.

Venzon, Anne Cipriano. From Whaleboats to Amphibious Warfare: Lt. Gen. “Howling Mad” Smith and the U.S. Marine Corps. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2003.