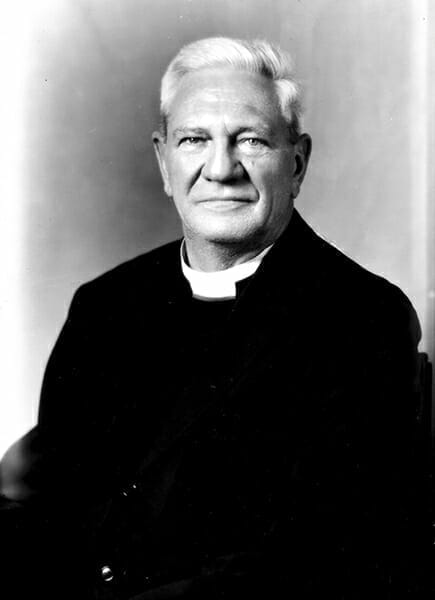

Charles Carpenter Sr.

Charles Carpenter

Charles Colcock Jones Carpenter Sr. (1899-1969) served as bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama from 1938 to 1968. He was the youngest member of the Episcopal House of Bishops when elected and the oldest member when he retired. Carpenter is most often remembered, however, for impeding racial integration in the Episcopal Church in Alabama. He was one of eight religious leaders who urged Martin Luther King Jr. to refrain from demonstrating in Birmingham, Jefferson County, in 1963 and as such was an intended recipient of King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Carpenter was otherwise an effective and successful bishop who increased the baptized membership of the Alabama diocese and its budget and oversaw the establishment of several important institutions.

Charles Carpenter

Charles Colcock Jones Carpenter Sr. (1899-1969) served as bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama from 1938 to 1968. He was the youngest member of the Episcopal House of Bishops when elected and the oldest member when he retired. Carpenter is most often remembered, however, for impeding racial integration in the Episcopal Church in Alabama. He was one of eight religious leaders who urged Martin Luther King Jr. to refrain from demonstrating in Birmingham, Jefferson County, in 1963 and as such was an intended recipient of King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Carpenter was otherwise an effective and successful bishop who increased the baptized membership of the Alabama diocese and its budget and oversaw the establishment of several important institutions.

Carpenter was born September 2, 1899, in Augusta, Georgia, to Ruth Berrien Jones and Samuel Barstow Carpenter, an Episcopal priest originally from Detroit who died when Carpenter was only 12 years old; he had two sisters. Carpenter was descended from Georgia’s plantation and slave-owning aristocracy. His grandfather Charles Colcock Jones Sr. was a Presbyterian minister who came to be known as the “apostle to the Negroes.” As a student at Princeton, Jones gave serious thought to becoming an abolitionist but would later abandon abolitionism and own slaves, although he then devoted himself to their education and evangelization.

After attending the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey, Carpenter served briefly as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army at the very end of World War I but was never sent overseas. The tall, athletic Carpenter graduated from Princeton University in New Jersey, where he was the Ivy League wrestling champion, in 1921. (Princeton later gave Carpenter an honorary doctorate in 1947.) He then studied at the Virginia Theological Seminary, an institution in Alexandria, Virginia, aligned with the evangelical wing of the Episcopal Church with which Carpenter strongly identified. He was ordained to the priesthood in June 1926 and his first parish was Grace Episcopal Church in Waycross, Georgia. In 1928, Carpenter was appointed to serve as archdeacon of the Georgia diocese and in the same year married Alexandra Morrison, with whom he had four children.

Carpenter was nominated to be bishop of Georgia in 1934. But the convention for the election was unable to select a bishop after 12 ballots and Carpenter was not re-nominated. When Charles Clingman, rector of Birmingham’s Church of the Advent, was elected bishop of Kentucky, the Advent leadership called on Carpenter to be their rector. Two years later, Bishop William George McDowell died, and a special convention of the Alabama diocese chose Carpenter to be its sixth bishop.

Under Carpenter’s direction, and aided by post-World War II population growth, the Alabama diocese thrived. During the 1950s and early 1960s, many parishes were established or expanded. One of Carpenter’s most significant achievements was the founding of Camp McDowell in Nauvoo, Winston County, the first permanent center for recreation and spiritual renewal enjoyed by both the young people and adults in the Diocese of Alabama. Carpenter also lent his support to the building of the St. Martin’s in the Pines residential facility for seniors in Irondale, Jefferson County. In 1955, Carpenter was part of a group that formed the Episcopal Foundation of Jefferson County, which raised $325,000 and acquired federal funds from the Hill-Burton Act to build a housing unit in 1958 that accommodated 40 residents. Bishop Carpenter laid the cornerstone on Palm Sunday, March 22, 1959.

From its beginning, however, Carpenter’s term as bishop was troubled by racial issues. With few exceptions, black and white Episcopalians worshiped in separate churches prior to the civil rights movement. In 1939, a white professor brought some African American students from Talladega College to St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Talladega, but the rector, Robert C. Clingman, turned them away, believing that the congregation would be reluctant to accept African American members. Carpenter supported that decision, and the controversy at St. Peter’s continued for years. In 1951, Carpenter opposed the enrollment of African American students at the University of the South’s School of Theology (located in Sewanee, Tennessee), which had been recommended by the governing bodies of the dioceses located in the South. In a letter to a trustee from Mobile, Carpenter said that he would recommend tabling the recommendation because of opposition from southern Episcopalians.

Carpenter seems not to have made any public comments about race relations until the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education school integration decision. One year after the decision, he told the diocesan convention that the Supreme Court had created a “very difficult predicament” and urged Alabama’s Episcopalians to work together to ease racial tensions. In the aftermath of Brown and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Carpenter assembled a committee that included African American members to study the issue of recruiting black clergy. The black committee members soon realized, however, that the purpose of the committee was to preserve segregation, presumably by expanding black congregations rather than by opening white congregations to black members.

Carpenter came into indirect conflict with Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963 and again in 1965. In 1963, Carpenter and his assistant George Murray, as well as six other white religious leaders issued “A Call for Unity,” a statement urging Birmingham’s African American community to withdraw its support from the demonstrations that King planned to launch in downtown Birmingham during Holy Week. King offered a devastating reply to that statement in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in which he artfully defended his reasons for the demonstrations and admonished white moderates for their complicity in racial oppression.

In 1965, Carpenter did everything in his power to prevent Episcopalian clergy from participating in King’s Selma to Montgomery March for voting rights on March 21. He urged Episcopalians to refrain from taking part in the demonstrations and was dismayed when leaders of his own church participated. In fact, he broke with longtime friend John B. Hines, presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church, who, with the National Council of Churches, declared the Selma march a “recognized ecumenical activity,” allowing Episcopal clergy to participate without Carpenter’s permission. Ultimately, more than 500 Episcopalian clergy, including Hines, came to Selma. But when Selma’s St. Paul’s Episcopal Church turned away black worshipers who had come to Selma for the march, Carpenter negotiated with the rector and leadership of the parish who ultimately admitted black and white demonstrators, although they continued to practice segregated seating during the services.

After Tom Coleman was acquitted of the August 1965 murder of Episcopal seminarian Jonathan Myrick Daniels, Carpenter issued a weak and ambiguous statement. He lamented that he had overheard many church members “condoning the slaying or beating of civil rights’ workers” and feared that Alabama would be subjected to federal intervention if state leaders appeared unable to govern in a just manner. For these and other perceived acts of indifference and inaction, Carpenter was heavily criticized by other Episcopalian leaders elsewhere in the country.

Unlike his fellow bishops Duncan Gray of Mississippi, William Marmion of southern Virginia, and Will Scarlett of Missouri, who all managed to speak out clearly and unambiguously in favor of civil rights while continuing to pastor their flocks effectively, Carpenter tried to steer a middle course between the segregation of his youth and the integration demanded by King and others. For some Episcopalians, Carpenter’s moderation went too far, but for most, he did not go nearly far enough.

At the beginning of Carpenter’s episcopacy, the total baptized membership of the Diocese of Alabama was just over 19,250, the diocese had 35 parishes, and the annual budget was $38,550. When he retired, there were nearly 33,400 baptized members, 53 parishes, and a budget of $105,600, producing an impressive record for any bishop of Alabama. By most standards, Carpenter must be judged an effective and successful bishop in many regards. But unlike other southern bishops, Carpenter did not clearly and forcefully address the fear and anger that kept many of his white communicants from embracing educational and economic opportunities for African Americans that white people took for granted. When Carpenter retired, he left not only a heritage of growth but also a legacy of incomplete racial reconciliation. Carpenter announced his retirement at the Diocesan Convention in January 1968 and officially retired at the end of the year. On June 28, 1969, Carpenter died in his sleep.

Additional Resources

Bass, S. Jonathan. “Bishop C.C.J. Carpenter: From Segregation to Integration.” Alabama Review 45 (July 1992): 184-215.

Bass, S. Jonathan. Blessed are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King, Jr., Eight Religious Leaders, the Media, and the Letter from Birmingham Jail. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996.

Carpenter, Douglas M. A Powerful Blessing: The Life of Charles Colcock Jones Carpenter, Sr., 1899-1969. Sixth Episcopal Bishop of Alabama, 1938-1968. Birmingham: TransAmerica Printing, 2012.

Vaughn, J. Barry. Bishops, Bourbons, and Big Mules: A History of the Episcopal Church in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2013.