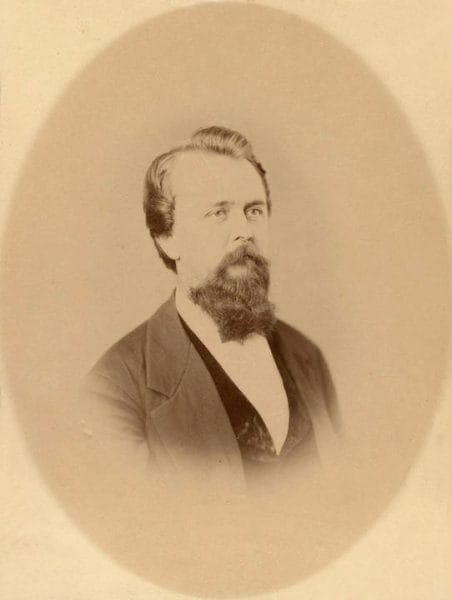

Hilary Abner Herbert

Hilary Abner Herbert

Hilary Abner Herbert (1834-1919) was an important southern politician during the period following the Civil War and into the early twentieth century. Herbert dedicated much of his life to public service; he was a representative to the U.S. Congress for Alabama from 1877 to 1893 and served as Secretary of the Navy from 1893 to 1897, being the first Alabamian to hold a cabinet position. In both positions, he successfully advocated for a larger, more modern force. Despite being an avid apologist for the South on race relations and the Civil War, Herbert viewed his public service as an arena in which to reconcile the North and South.

Hilary Abner Herbert

Hilary Abner Herbert (1834-1919) was an important southern politician during the period following the Civil War and into the early twentieth century. Herbert dedicated much of his life to public service; he was a representative to the U.S. Congress for Alabama from 1877 to 1893 and served as Secretary of the Navy from 1893 to 1897, being the first Alabamian to hold a cabinet position. In both positions, he successfully advocated for a larger, more modern force. Despite being an avid apologist for the South on race relations and the Civil War, Herbert viewed his public service as an arena in which to reconcile the North and South.

Herbert was born on March 12, 1834, in Laurensville (present-day Laurens), South Carolina, to Dorothy Teague and Thomas Herbert. He had four sisters and had several brothers who did not survive childhood. His parents were moderately wealthy, running the Laurensville Female Academy and owning a plantation. The Herberts were slaveowners who were notable among their peers for keeping the marriages of their enslaved workers intact, and at one time Dorothy Herbert was an abolitionist. It is from this environment that Herbert likely developed his paternalistic view on African American rights. Herbert acknowledged the evils of slavery after the South’s defeat and Emancipation, but he certainly would not be considered racially tolerant by modern standards.

Herbert’s family relocated to Greenville, Butler County, in 1846. The move may have been prompted by either a desire to join relatives there or because it had a lower enslaved population than other Black Belt counties, and Herbert’s mother feared a slave revolt after several incidents in the mid-Atlantic states. Once in Butler County, the family established a plantation and the Greenville Female Academy, which would later be known as the South Alabama Institute. Herbert attended the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia, before illness forced him to return home without a diploma in 1856, but with a strong belief in states’ rights and in the constitutionality of secession. He then studied law under a local judge and had become a successful lawyer by the start of the Civil War. Just after the 1860 presidential election, Herbert enlisted as a second lieutenant of the Greenville Guards, which later became part of the 8th Alabama Infantry Regiment; he rose through the ranks to captain. Wounded and captured during the June 1862 Battle of Seven Pines in Virginia and later released, Herbert suffered a more serious wound at the May 1864 Battle of the Wilderness in Virginia that crippled his left arm and forced him to return home; there he resumed his practice of law. Herbert married Ella Bettie Smith on April 23, 1867; the couple would have three children.

Hilary A. Herbert and Robert Lees Phythian

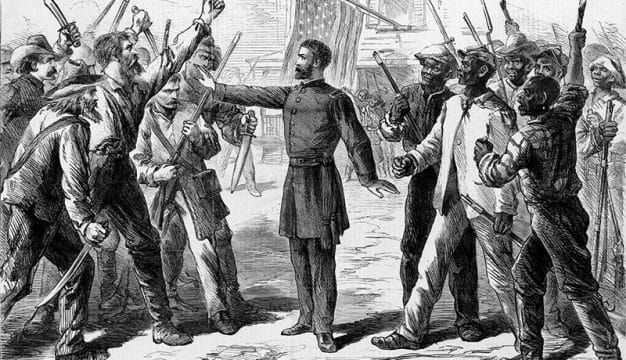

After the war, Herbert accepted the South’s defeat and came to see the war as a great catharsis for the nation. However, he deplored Reconstruction, which prompted him to enter politics. At times he courted African American voters, but he criticized their enfranchisement and strove to ensure white supremacy in the South. He emerged as a powerful Bourbon Democrat, succeeding Jeremiah Williams for the seat representing Alabama’s Second Congressional District, made up of several counties in south-central Alabama, including Montgomery. Herbert served from 1877 to 1893, winning reelection with little difficulty seven times, despite his district’s large African American population. He sat on the influential Ways and Means and Judiciary committees but took special interest in his work on the Naval Affairs Committee. America’s navy had been neglected since the Civil War and was in desperate need of modernization. Herbert, as chairman of the panel from 1885 to 1893, played a leading role in convincing many in his party to support naval expansion for the first time, advocating for increased appropriations and authorizing the construction of several battleships and numerous cruisers and other heavily armed vessels.

Hilary A. Herbert and Robert Lees Phythian

After the war, Herbert accepted the South’s defeat and came to see the war as a great catharsis for the nation. However, he deplored Reconstruction, which prompted him to enter politics. At times he courted African American voters, but he criticized their enfranchisement and strove to ensure white supremacy in the South. He emerged as a powerful Bourbon Democrat, succeeding Jeremiah Williams for the seat representing Alabama’s Second Congressional District, made up of several counties in south-central Alabama, including Montgomery. Herbert served from 1877 to 1893, winning reelection with little difficulty seven times, despite his district’s large African American population. He sat on the influential Ways and Means and Judiciary committees but took special interest in his work on the Naval Affairs Committee. America’s navy had been neglected since the Civil War and was in desperate need of modernization. Herbert, as chairman of the panel from 1885 to 1893, played a leading role in convincing many in his party to support naval expansion for the first time, advocating for increased appropriations and authorizing the construction of several battleships and numerous cruisers and other heavily armed vessels.

Herbert’s other main concern in Congress was preventing additional federal intervention in southern affairs. Toward this effort, he authored Why The Solid South? in 1890, a work meant to change how the nation viewed Reconstruction. The book consisted of essays by statesmen from the 11 states of the former Confederacy concerning their perceived horrors of Reconstruction and was the most comprehensive and articulate statement given from the southern point of view up to that time. The work praised Abraham Lincoln as a great statesman and mourned his death, arguing that his original goals for Reconstruction had been ignored by the radicals in Congress who had implemented Congressional Reconstruction. Restrained and coherent, rather than angry or vindictive, the book was widely influential among revisionists and so-called Redeemers and was moderately successful in helping to convince readers that the South had been dealt with too harshly following the war.

Faced with rising opposition in his district, Herbert did not stand for reelection in 1892. But, owing to his service on the Naval Affairs Committee, he was appointed by Pres. Grover Cleveland as Secretary of the Navy in 1893 and served until 1897. (His open congressional seat was won by Jesse Stallings.) Under Herbert’s guidance, the U.S. fleet modernized and advanced from the nineteenth to the seventh most powerful Navy in the world and, enabling the United States to later play a much larger role in international affairs, most notably distinguishing itself during the Spanish-American War in 1898.

After retiring from politics, Herbert returned to a successful law practice he had previously established in Washington, D.C., gave lectures, and wrote The Abolitionist Crusade and Its Consequences: Four Periods of American History, a book that blamed radical abolitionists for starting the Civil War. He was, however, a voice of moderation during the racial upheavals of the time, opposing lynching and other violence against African Americans while still maintaining a belief in white supremacy. Herbert died in Tampa, Florida, on March 6, 1919, and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery. In honor of his service to the U.S. Navy, the destroyer U.S.S. Herbert (DD-160) was commissioned in November 1919 and served through World War II.

Further Reading

- Hammett, Hugh. Hilary Abner Herbert: A Southerner Returns to the Union. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1976.