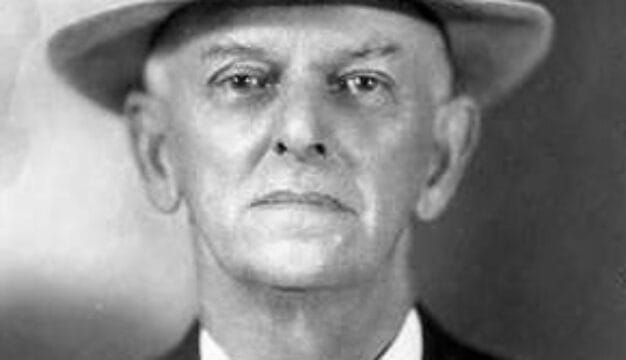

Menawa

Chief Menawa

Menawa was one of the most famous Creek Indians of the nineteenth century. He is best known for his leadership in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the most defining battle of the Creek War of 1813-14. Nothing is known about his activities in other significant events of the conflict, but he probably participated in most of the battles involving the warriors from his Creek town of Okfuskee, including the battles at the Creek encampment of Emuckfau and with Gen. Andrew Jackson’s forces at Enitichopco Creek. He is generally acknowledged to have been the leader of the Red Stick forces at Horseshoe Bend, but his role in the establishment of the much-noted defensive fortifications and other preparations for battle are unknown.

Chief Menawa

Menawa was one of the most famous Creek Indians of the nineteenth century. He is best known for his leadership in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the most defining battle of the Creek War of 1813-14. Nothing is known about his activities in other significant events of the conflict, but he probably participated in most of the battles involving the warriors from his Creek town of Okfuskee, including the battles at the Creek encampment of Emuckfau and with Gen. Andrew Jackson’s forces at Enitichopco Creek. He is generally acknowledged to have been the leader of the Red Stick forces at Horseshoe Bend, but his role in the establishment of the much-noted defensive fortifications and other preparations for battle are unknown.

Menawa was born around 1765, the son of a Creek woman and an Anglo-American deerskin trader. His early fame rested on his exploits against settlements in what is now Tennessee, where he raided encroaching American farms for horses. For his exploits, he was given the name Hothlepoya, or “crazy war hunter.” By 1811, he was the second chief of the Okfuskee towns and had acquired the name Menawa, which is translated as “The Great Warrior.” By then, he operated a trading store, owned large herds of cattle and hogs, and traded horses and peltry with companies in Pensacola. However, Menawa did not enjoy his wealth and success for long.

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend, fought March 27, 1814, pitted an American army of 3,300 men led by Andrew Jackson against nearly 1,000 Creek warriors of the Red Stick faction from the Okfuskee towns; they had gathered in a bend of the Tallapoosa River and fortified the neck of the bend all the way across with a wooden barricade. Various secondary accounts of the battle provide garbled accounts of Menawa’s conduct during the battle and even the manner in which he escaped capture. According to a short biographical sketch of Menawa by Thomas McKenney, who served as the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and met the chief after the war, Menawa turned against one of the leading Creek prophets early in the battle and, after killing him, led the Red Sticks in defending the breastworks the Creeks had previously erected. The McKenney account is undermined by one of Jackson’s lieutenants, John Reid, who, in his Life of Jackson, wrote that the leading prophet, Monohe, was killed by cannon fire early in the battle.

According to McKenney, Menawa suffered seven gunshot wounds defending the barricade and later in the battle was shot in the face, the rifle bullet entering just under his ear and exiting the other cheek, knocking out several of his teeth. As the battle progressed, he was left among the dead and wounded and managed to escape the battlefield under cover of darkness. The exact manner of his escape has been reported in various ways, but the most logical, presented by McKenney, asserts that the chief was able to crawl to a canoe, rock it loose from the bank, and then float down the Tallapoosa River, where the canoe was intercepted by Creek women hiding in a canebrake. After the battle, Menawa and other surviving Okfuskee warriors and noncombatants sought refuge in what is now Shelby County, near the falls of the Cahawba River, now known as Falling Rock Falls.

Menawa’s considerable wealth was destroyed by the war. However, his reputation as a military hero and a leader kept him in the spotlight, and he was the only leading Red Stick warrior who remained prominent in Creek political affairs after the war as a member of the Creek National Council. Owing to his status as a warrior, he was dispatched by the National Council with the party of “law menders” (as the Creek police force was known) sent to execute the Creeks who had signed the unauthorized Treaty of Indian Springs (1825) for violation of Creek national law. The deputation, estimated at between 120 and 150 Creek men, executed Tustunnuggee Hutkee (William McIntosh) as well as two other chiefs who had signed the treaty.

Menawa was part of the official Creek delegation sent to Washington, D.C., in late 1825 to protest the illegal treaty, which had forfeited Creek land east of the Chattahoochee River to Georgia. Thomas McKenney, then head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, praised Menawa’s character, noting his dignity and leadership during the negotiations. The Creeks were successful in having the unauthorized treaty abrogated, despite it being ratified by the U.S. Senate. But the Creek leaders were unable to regain their lost Georgia lands, although they did recover some territory in what later became the state of Alabama. The Treaty of Indian Springs remains the only treaty ever ratified by the United States that was later overturned.

While the Creeks were in Washington, McKenney commissioned a series of portraits of the delegates, including Menawa, by painter Charles Bird King. The original portraits became the property of the United States and were destroyed by a fire in the Smithsonian in early 1865. Fortunately, prior to their destruction, McKenney had hired Henry Inman, another portrait artist, to make copies of most of them; these paintings then were used by both artists to produce engravings for the lithographs published in McKenney’s much-lauded three-volume History of the Indian Tribes of North America.

After he returned to the Creek Nation, Menawa continued to oppose Indian removal in the face of increasing pressure from the state of Alabama and the federal government. In a last-ditch effort to remain in Alabama, in 1832 the Creek National Council agreed to the assignment of the tribal lands to individual Creeks, effectively ending Creek sovereignty over their remaining homeland. Under the 1832 Treaty of Cusseta, all Creek heads of household were awarded 320 acres of land, with chiefs awarded 640 acres. Individual Indian owners were guaranteed the right to either keep their individual holdings and live under Alabama law or sell and remove to Indian Territory. Menawa supported dissolution of Creek sovereignty to retain some land ownership. He reportedly visited the Catawba Indians in North Carolina to observe their experiences living in close proximity to non-Indians and to investigate the situation of Indians living under state law. According to the census undertaken to ascertain the number of heads of household, Menawa’s family was reported to contain two men and four women, and he received a parcel of 638.92 acres in what is now Tallapoosa County in May 1835.

After the dissolution of Creek government and the opening of Creek territory for sale and survey, chaos ensued. In addition to outright violence against Indians in an attempt to force them to sell their holdings and leave the area, illegal squatting by white settlers and fraudulent land speculation practices made it impossible for Creek people to retain their property or assimilate into Alabama society. Menawa’s town of residence, the Okfuskee “daughter” town of Chataksofke (located near the modern town of Dadeville), was taken illegally and sold by speculators, and the allotment given to Menawa was not the land where his property was located.

The defrauding and treatment of Creeks resulted not only in federal-state conflict over the allotment process but also led to a Creek uprising known as the Second Creek War. This conflict, which erupted in 1836, was mainly centered along the Chattahoochee River Valley. Menawa met personally with Alabamians who lived near him to assure them that his townsmen would not participate. In early June 1836, he was one of the leaders of the 1,200 Creek warriors who joined the Americans against Creek dissidents. His action on behalf of peace proved futile, and the United States government used the Second Creek War as an excuse to order the forced removal of all Creeks, hostile or not, by the military. Menawa and his family were moved west in 1836 in a detachment of 2,420 Creek Indians. The group assembled near Talladega and then moved north to Memphis. There, Menawa and many others refused to board steamboats, and the detachment split, some traveling to Little Rock, Arkansas, by steamboat and others, like Menawa, then 70 years old, moving overland.

The record is silent on when the famed chief arrived in Indian Territory and on his last years and final resting place in the west.

Further Reading

- Ellisor, John. The Second Creek War: Interethnic Conflict and Collusion on a Collapsing Frontier. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

- Green, Mike. The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

- McKenney, Thomas L., and John Hall. History of the Indian Tribes of North America, with Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of the Principal Chiefs. Embellished with One Hundred and Twenty Portraits, from the Indian Gallery in the Department of War, at Washington. 3 Vols. Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1836-44.