Fort Bowyer

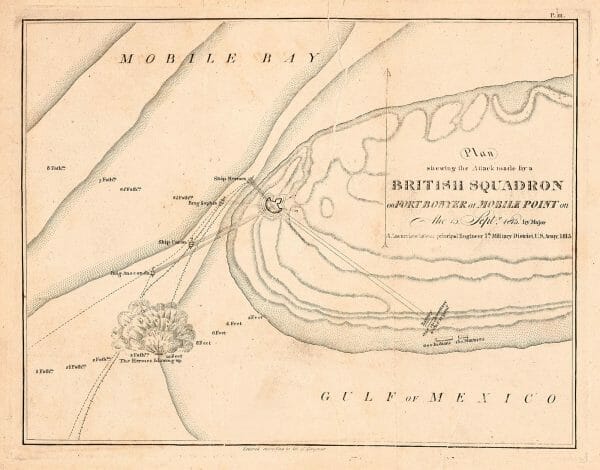

Fort Bowyer was a small wooden fort built on the sands of Mobile Point peninsula to guard the entrance to Mobile Bay during the War of 1812; it was located near the site of present-day Fort Morgan. Fort Bowyer was an important part of the defenses of Mobile, Mobile County, during the war. The fort withstood one British assault in September 1814, altering British plans to take New Orleans, but succumbed to a second, much larger assault in February 1815 just before news arrived that a peace treaty had been signed. Therefore, it is widely considered to be the site of the last land battle between the United States and the British in the War of 1812.

Mobile Point and Fort Bowyer

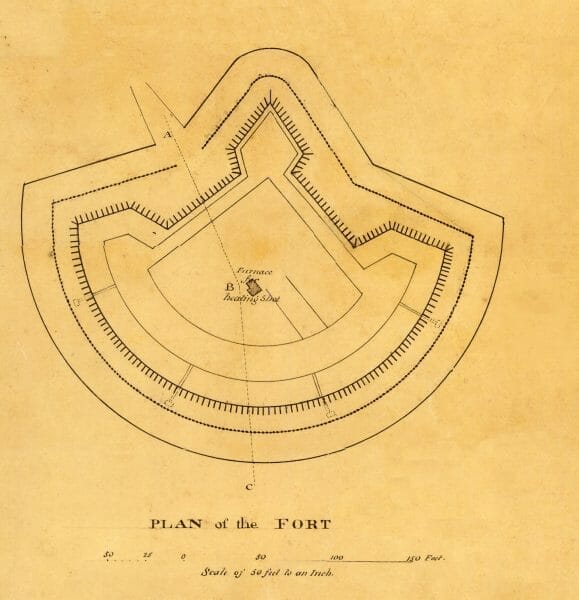

Maj. Gen. James Wilkinson, the commanding U.S. Army officer in Mobile, began construction on the fort after the Spanish surrendered the port city in April 1813. In June 1813, Col. John Bowyer, for whom the fort was named, took command and completed the work. Fort Bowyer was roughly 22,000 square feet, with a semicircular wall roughly 400 feet long facing the bay entrance and two straight walls on the land side, each roughly 60 feet in length, connecting at a bastion. Brig. Gen. Thomas Flournoy, Wilkinson’s successor in Mobile, ordered Bowyer to abandon the fort in the summer of 1814. In August 1814, Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson took command of U.S. forces in Mobile and, anticipating a British attack on the town, sent 160 U.S. Army regulars and approximately a dozen cannon under Maj. William Lawrence to reoccupy and repair the fort.

Mobile Point and Fort Bowyer

Maj. Gen. James Wilkinson, the commanding U.S. Army officer in Mobile, began construction on the fort after the Spanish surrendered the port city in April 1813. In June 1813, Col. John Bowyer, for whom the fort was named, took command and completed the work. Fort Bowyer was roughly 22,000 square feet, with a semicircular wall roughly 400 feet long facing the bay entrance and two straight walls on the land side, each roughly 60 feet in length, connecting at a bastion. Brig. Gen. Thomas Flournoy, Wilkinson’s successor in Mobile, ordered Bowyer to abandon the fort in the summer of 1814. In August 1814, Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson took command of U.S. forces in Mobile and, anticipating a British attack on the town, sent 160 U.S. Army regulars and approximately a dozen cannon under Maj. William Lawrence to reoccupy and repair the fort.

Fort Bowyer Diagram

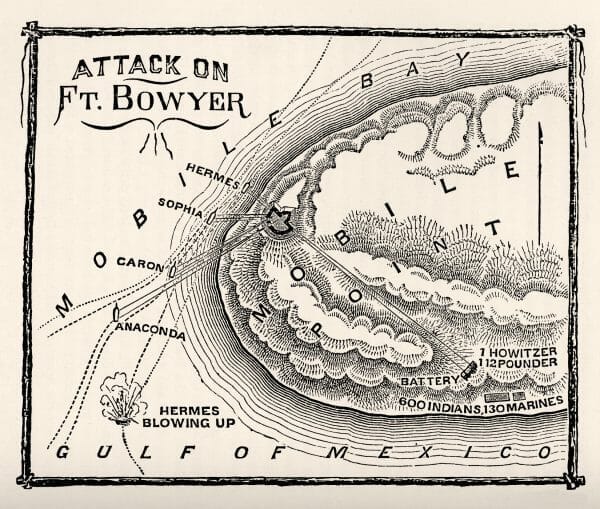

Jackson’s fears proved to be well-founded when the British attempted to take Mobile in September 1814. The British commanders in the Gulf region hoped to capture Mobile and use it as a staging area to capture New Orleans. They hoped to march westward to the Mississippi River north of the city. With control of the Mississippi to the north of New Orleans, and a naval blockade of the Gulf Coast to the south, the British would be able to keep supplies and reinforcements from reaching New Orleans. New Orleans would then be vulnerable to British capture. On September 12, four small British war ships with 78 cannon under Capt. William Percy arrived from Pensacola and anchored off Fort Bowyer. The ships landed about 60 British marines and 180 Native Americans (likely Creeks and Seminoles), commanded by Maj. Edward Nicolls, nine miles east of the fort. Unfavorable winds and shoals prevented the ships from approaching Fort Bowyer until September 15. Even then, only two of the British ships, the Sophie and the Hermes, could get close enough to fire on the fort. The men on the two ships and the American soldiers in the fort exchanged fierce cannon fire. An American shot disabled the Hermes, which drifted near the fort and suffered severely from the American cannonade. After the ship ran aground, its crew abandoned the vessel and blew it up.

Fort Bowyer Diagram

Jackson’s fears proved to be well-founded when the British attempted to take Mobile in September 1814. The British commanders in the Gulf region hoped to capture Mobile and use it as a staging area to capture New Orleans. They hoped to march westward to the Mississippi River north of the city. With control of the Mississippi to the north of New Orleans, and a naval blockade of the Gulf Coast to the south, the British would be able to keep supplies and reinforcements from reaching New Orleans. New Orleans would then be vulnerable to British capture. On September 12, four small British war ships with 78 cannon under Capt. William Percy arrived from Pensacola and anchored off Fort Bowyer. The ships landed about 60 British marines and 180 Native Americans (likely Creeks and Seminoles), commanded by Maj. Edward Nicolls, nine miles east of the fort. Unfavorable winds and shoals prevented the ships from approaching Fort Bowyer until September 15. Even then, only two of the British ships, the Sophie and the Hermes, could get close enough to fire on the fort. The men on the two ships and the American soldiers in the fort exchanged fierce cannon fire. An American shot disabled the Hermes, which drifted near the fort and suffered severely from the American cannonade. After the ship ran aground, its crew abandoned the vessel and blew it up.

The British cannonade, however, did little damage to the fort. Meanwhile, the British land forces bombarded the fort but were too weak to attack it without naval support. After the battle, the remaining British ships and marines withdrew to Pensacola. The British suffered about 70 killed and wounded. One of the wounded was Nicolls, who had returned to the Hermes because of an illness and then suffered a head wound. The Americans suffered only about 10 killed and wounded, but Jackson decided to strengthen the defenses with 200 additional soldiers and perhaps another 10 cannon. According to several historians, the American victory at Fort Bowyer dimmed British hopes of attracting Native Americans to help them in their Gulf Coast campaign. It also prevented British forces from marching west overland along the Gulf Coast from Mobile to take New Orleans from the north. Instead, the British attempted a much more difficult assault on New Orleans from the sea and were turned back in the famous Battle of New Orleans.

Attack on Fort Bowyer

The British commanders then decided to make another attempt to take Fort Bowyer and Mobile. On February 7, they stationed a large naval squadron of 38 heavily armed warships around the peninsula. Under the cover of sand hills, the British landed approximately 1,300 soldiers behind the fort on February 8, while more British troops stood in reserve on Dauphin Island, across the bay. The British land forces began the siege by digging covering approach trenches through the sand to within 40 yards of the fort’s walls and establishing batteries consisting of cannon, howitzers, and mortars to bombard it from close range. In the face of such firepower on all sides and the lack of casemates (fortified gun placements) to shelter the wounded and protect the powder magazine, Lawrence considered further defense of the fort hopeless. He surrendered his roughly 370 men on February 12. During the siege, the British suffered about 30 killed and wounded, the Americans about 10. Most of these casualties resulted from exchanges of cannon and musket fire on the land side of the fort while the British were working to move their batteries into place.

Attack on Fort Bowyer

The British commanders then decided to make another attempt to take Fort Bowyer and Mobile. On February 7, they stationed a large naval squadron of 38 heavily armed warships around the peninsula. Under the cover of sand hills, the British landed approximately 1,300 soldiers behind the fort on February 8, while more British troops stood in reserve on Dauphin Island, across the bay. The British land forces began the siege by digging covering approach trenches through the sand to within 40 yards of the fort’s walls and establishing batteries consisting of cannon, howitzers, and mortars to bombard it from close range. In the face of such firepower on all sides and the lack of casemates (fortified gun placements) to shelter the wounded and protect the powder magazine, Lawrence considered further defense of the fort hopeless. He surrendered his roughly 370 men on February 12. During the siege, the British suffered about 30 killed and wounded, the Americans about 10. Most of these casualties resulted from exchanges of cannon and musket fire on the land side of the fort while the British were working to move their batteries into place.

The fall of Fort Bowyer opened Mobile to British attack. Some historians believe that, had the British captured Mobile, they would have renewed their campaign against New Orleans by the overland route, their original plan all along. The British still wanted to conquer the Gulf Coast and New Orleans and use them as bargaining chips to get concessions from American peace negotiators. Two days after Fort Bowyer fell, however, the British commanders received news that the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812 and all fighting in the region, already had been signed, and the fort was returned to the United States. The fort was later abandoned and essentially replaced by Fort Morgan.

Further Reading

- Coker, William S. “The Last Battle of the War of 1812: New Orleans. No, Fort Bowyer!” Alabama Historical Quarterly 43 (Spring 1981): 42-63.

- Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler. “‘Where All Behave Well’: Fort Bowyer and the War on the Gulf, 1814-1815.” In Tohopeka: Rethinking the Creek War and the War of 1812, edited by Kathryn E. Holland Braund, pp. 182-199. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2012.

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence, Jr. Struggle for the Gulf Borderlands: The Creek War and the Battle of New Orleans, 1812-1815. Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1981.