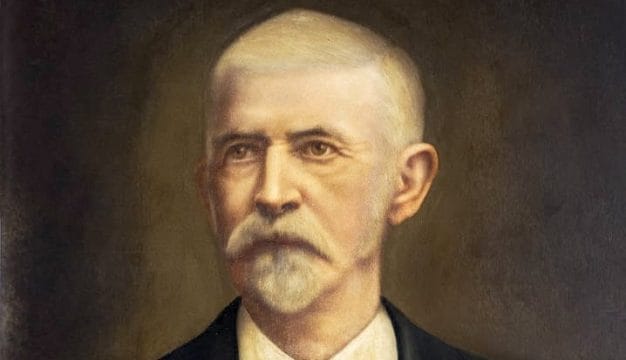

James G. Birney

James Gillespie Birney (1792–1857) was a major voice in the abolitionist movement of the nineteenth century and the first presidential candidate for the abolitionist Liberty Party. His lifelong struggle over the morality of slavery stemmed from his early life on plantations in Kentucky and Alabama, and the close relationships that developed between Birney and the people his family held in bondage.

James G. Birney

James G. Birney’s transition from slave owner to abolitionist began in Kentucky, where he was born on February 4, 1792. Both his father, James Birney Sr., and maternal grandfather, John Reed, supported the ideals of abolition but embraced the financial benefits conferred upon plantation owners by enslaved labor. In 1792, Birney Sr. and Reed attempted to prevent the spread of slavery by arguing against its introduction during Kentucky’s constitutional convention. Like many other prominent Kentucky politicians, they owned enslaved people, presenting an early and persistent intellectual challenge to a young James G. Birney. After his mother’s death in 1795, Birney’s paternal aunt, Margaret Doyle, came from Ireland to Danville, Kentucky, to help her brother raise James and his sister Anna Maria, also known as Nancy. At the age of six, he was given ownership of his first enslaved person, Michael Matthews; the two would maintain a close relationship throughout their lives.

James G. Birney

James G. Birney’s transition from slave owner to abolitionist began in Kentucky, where he was born on February 4, 1792. Both his father, James Birney Sr., and maternal grandfather, John Reed, supported the ideals of abolition but embraced the financial benefits conferred upon plantation owners by enslaved labor. In 1792, Birney Sr. and Reed attempted to prevent the spread of slavery by arguing against its introduction during Kentucky’s constitutional convention. Like many other prominent Kentucky politicians, they owned enslaved people, presenting an early and persistent intellectual challenge to a young James G. Birney. After his mother’s death in 1795, Birney’s paternal aunt, Margaret Doyle, came from Ireland to Danville, Kentucky, to help her brother raise James and his sister Anna Maria, also known as Nancy. At the age of six, he was given ownership of his first enslaved person, Michael Matthews; the two would maintain a close relationship throughout their lives.

James Priestly, a prominent Baptist minister and early antislavery advocate, tutored Birney for several years on the family’s plantation in Danville. Thus during Birney’s childhood, he received conflicting views on slavery. This conflict continued during his education at Princeton University, where he earned a degree in theology. Rev. Stanhope Smith, the president of Princeton, was an abolitionist who also owned enslaved people. He taught that humanity derived from a common ancestor, a concept that challenged conventional wisdom and weakened arguments for slavery.

Birney came to Alabama in 1818 and established a law practice and a plantation in Triana, Madison County. Because of his prestige as a lawyer and status as a planter, Birney easily entered politics and was elected to represent Madison County in the Alabama House of Representatives. Birney secured several antislavery provisions in the state’s first constitution, including the stipulations that enslaved people should receive a trial by jury for any crime more serious than theft, that slave owners must provide food and clothing to them, and that the murder or maiming of an enslaved person should be punished with the same vigor as a crime committed against a white victim. Though progressive in tone and scope, these provisions ultimately proved ineffective, as few white people cared to enforce them. While in Alabama, Birney soured towards the practice of slavery after witnessing the brutality integral to the plantation economy and the cotton regime. Birney’s inexperience with the cotton crop meant that his plantation quickly lost money, and in 1822, just two years after settling in Triana, these losses prompted him to move to Huntsville and practice law.

In 1819, Birney gave a political speech against Andrew Jackson’s invasion of Spanish-held Florida. Jackson’s conduct during the Battle of New Orleans and his removal of much of the Creek Nation from lower Alabama during the War of 1812 meant that he remained popular throughout the state. Opposition to Jackson’s military campaign diminished Birney’s influence outside of north Alabama. He regained some of that influence after being appointed president of the Huntsville Board of Trustees in 1823. He then led reform movements in the city as an alderman, including unsuccessful attempts to outlaw alcohol and a successful attempt to fund public education. Birney also held a position as a founding member of the Huntsville Library Company, the oldest public library in the state. His interest in education prompted him to join other prominent citizens of Huntsville in recruiting students of the famed educator Catherine Beecher, sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe, for the Huntsville Female Seminary.

In addition to education and his tenure as alderman, Birney involved himself in the daily operations of Huntsville. He introduced a resolution to create a reservoir in case of fire and served on the organizing committee. Concern with the health of the Big Spring, part of the city’s water supply, mirrored Birney’s progressive ideals. He voted for a cleanliness law that prohibited polluting the city’s water supply. The punishments for polluting the spring, however, proved biased. A free person caught polluting the Big Spring paid a fine of five dollars, whereas an enslaved person received a hundred lashes.

Birney also affected events in neighboring counties and attempted to intervene in national politics. While serving as a state prosecutor from 1823 to 1827, Birney successfully sued a lynch club, an informal yet effective group of vigilantes, based in Jackson County. Several prominent men from Jackson County had joined the organization, and they often attacked settlers accused of counterfeiting. Birney’s passion for justice and continuing frustration with the policies of Andrew Jackson is evident in an 1832 letter to Alabama congressman Clement Comer Clay. In it, he pleaded with Clay to intervene on the behalf of the Cherokee Nation to prevent their removal from Georgia.

Birney left his law practice in 1832 to work as an agent for the American Colonization Society, traveling throughout the South raising funds for the immigration of free blacks and manumitted slaves to Liberia. These actions caused his neighbors in Huntsville to view him with suspicion and led to Birney’s moving back to Kentucky during the latter 1830s, where he finally freed his slaves. An 1834 letter to the Kentucky Colonization Society reveals the strength of his convictions. In it, Birney instructs slaveholders who remained apprehensive of manumission, for fear of an African American revolt or competition for jobs, to go before their slaves and beg forgiveness for their trespasses against the laws of God and human decency and count on their humanity.

After William Lloyd Garrison and other prominent abolitionists criticized colonization efforts in The Liberator, Birney abandoned that idea in favor of immediate and widespread emancipation. Between 1835 and 1837, the Birney family resided in Kentucky, near the Ohio River, where Birney printed his newspaper, The Philanthropist, from a small press outside of Cincinnati. His abolitionist sentiments proved as unpopular in the port city as in Alabama or Kentucky, and his press was destroyed during the 1836 Cincinnati Riots. The riots were a violent mob action in which poor whites and other Ohioans, frustrated with the growing presence of the abolitionist movement, targeted African Americans and those who were sympathetic to their plight. After this setback, Birney took a position as an agent with the American Anti-Slavery Society and resided in New York until 1840, when he resigned over his distaste for Garrison’s positive attitudes towards female suffrage. He stood for office in the 1840 and 1844 presidential elections as the Liberty Party candidate, garnering 2.3 percent of the vote in the 1844 race. According to the Alabama State Bar, Birney’s participation prevented the Whig candidate Henry Clay from winning New York, thus giving the election to James K. Polk.

Following the death of his first wife, Agatha Birney, the abolitionist schism, and his loss in the 1840 presidential election, Birney married Elizabeth Fitzhugh and moved his family to Michigan. There, he practiced law and used the experiences gained from local government in Huntsville to participate in the establishment of Bay City, Michigan. Birney fathered 14 children, four boys and ten girls. Most died before reaching adulthood, including three children who died in Huntsville and are buried in unmarked graves in Madison County. Three sons survived, however, and two of them, William and David, served as generals for the Union Army during the Civil War. His son James Birney became an influential senator in Michigan.

Further Reading

- Rogers, D. Laurence. Apostles of Equality: The Birneys, the Republicans, and the Civil War. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2011.

- Williams, Gladys. “James Gillespie Birney: The Evolution of an Abolitionist.” Alabama Historian 2 (April 1980): 11-15.