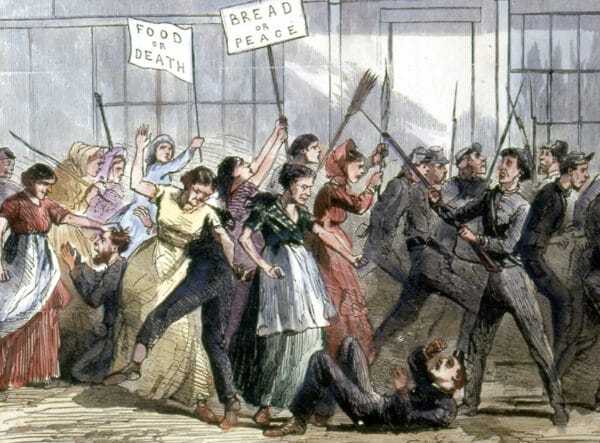

Mobile Bread Riot

The Mobile Bread Riot, which occurred on September 4, 1863, during the Civil War, was the result of rising prices and food shortages caused by the U.S. Navy’s blockade of Mobile Bay. The riot was a notable instance of dissatisfaction in Alabama with the course of the war. It also stands out as a significant example of south Alabama’s economic hardship during the conflict.

Mobile Bread Riot, 1863

As home to Alabama’s only deep-water port, Mobile, Mobile County, had prospered from the cotton boom of the mid-nineteenth century. By the outbreak of the Civil War, the port was one of the largest in the South. The federal blockade of Mobile Bay, begun in the summer of 1861, eventually would cut off almost all imports to the city. As a result, Mobile relied heavily on the interior regions of Alabama and Mississippi for food and other goods, such as pork, flour, and whiskey. As the war dragged on, such items became a luxury that only the wealthiest of Mobile families could afford.

Mobile Bread Riot, 1863

As home to Alabama’s only deep-water port, Mobile, Mobile County, had prospered from the cotton boom of the mid-nineteenth century. By the outbreak of the Civil War, the port was one of the largest in the South. The federal blockade of Mobile Bay, begun in the summer of 1861, eventually would cut off almost all imports to the city. As a result, Mobile relied heavily on the interior regions of Alabama and Mississippi for food and other goods, such as pork, flour, and whiskey. As the war dragged on, such items became a luxury that only the wealthiest of Mobile families could afford.

With prices rising and the value of the Confederate dollar falling, Mobilians reacted harshly to the many instances of profiteering. In the spring of 1862, citizens called for, and received, a new law aimed at curbing excessive profits by prohibiting the stockpiling foodstuffs by companies or individuals. The citizens of Mobile also dismissed an attempt by city officials to pay for strengthened defenses of the city with a voluntary tax. As daily necessities became scarcer, Mobilians were forced to adapt. Old clothes were dyed to make them look new. Handmade pants and dresses replaced imports made of fine fabric. When the oil for the city’s street lamps ran out, workers replaced it with pitch and hard pine knots.

The riot of September 1863 was not a surprising event to some. Several city leaders had predicted such a possibility for some time because of the reluctance of Confederate authorities to reduce high prices and the frequency of food shortages in the city. Early in the war, city officials and private citizens organized several groups to reduce the severity of food shortages and care for the families of soldiers killed in battle. Some of the wealthiest Mobilians contributed to the Mobile Supply Association, which sold necessary goods at cost in an attempt to keep inflation in the city under control. None of these efforts succeeded: by the spring of 1862 prices for certain foods were reported as soaring to as much as 750 percent above cost. By 1863, molasses, which before the war sold for less than $.30 per gallon, rose to $7.00 per gallon, and the cost of a barrel of flour rose from $44.00 to more than $400.00.

During the winter of 1862-63, Confederate general John C. Pemberton, who was in charge of forces in Mississippi and eastern Louisiana, issued an order that prohibited corn from being transported outside of Mississippi an effort to ease shortfalls in that state. Corn had become a staple food because the federal blockade also prevented intercoastal transport from New Orleans, and Mobile was directly affected by this order. The city’s mayor, Robert H. Slough, and Alabama governor John Gill Shorter appealed unsuccessfully to Pemberton to reconsider the order. Reaction among Mobilians to worsening conditions was predictable. In April, Mobile’s newspapers wrote harsh editorials about Pemberton’s order. Angry citizens painted inflammatory signs about the food crisis and dissatisfaction with the war effort and placed them around town. Fearing a more violent reaction, the Confederate government created new commissaries in each state. Still, the food shortages continued through the summer of 1863.

The simmering discontent in Mobile boiled over on Friday, September 4, 1863. Dozens of people, most of them women, gathered outside of the city near the present-day community of Spring Hill. The crowd marched into Mobile, their numbers growing along the way. News of the mob spread quickly, and soon Dauphin Street, the center of the city’s business district, was filled with rioters armed with axes, brickbats, hammers, and brooms. The women carried signs reading “Bread or Blood” and “Bread and Peace.” Spectators watched as the women broke windows and looted stores, taking food, clothing, and other household items. The stores of Jewish merchants fared the worst in the day’s events, perhaps because the rioters believed these merchants to be somehow more responsible than others for the high inflation in the city.

Gen. Dabney H. Maury dispatched the Seventeenth Alabama Regiment to quell the riot, but the soldiers refused to intervene. The Mobile Cadets, a local military company, also were unsuccessful in stopping the looting. The task of ending the riot fell to Slough, who effectively pleaded with the rioters to disperse, promising to meet with representatives to hear their complaints. The mayor also addressed the citizens of Mobile through a letter in the evening paper, asking wealthier Mobilians to contribute money for the purchase of food and clothing. From this plea, the Special Relief Committee was created to distribute the supplies to the neediest citizens.

News of the incident, which occurred just six months after the infamous bread riots in the Confederate capitol of Richmond, Virginia, spread throughout the country. An eyewitness account of the riot was published in several newspapers, including the New York Times and Harper’s Weekly. Although food shortages continued to plague Mobile throughout the war, no more riots occurred. The end of the war brought small relief to the citizens of Mobile; more than a generation would pass before the economy of Alabama’s port city stabilized.

Additional Resources

Bergeron, Arthur W., Jr. Confederate Mobile. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991.

McKiven, Henry M., Jr. “Secession, War, and Reconstruction, 1850-1874.” In Mobile: The New History of Alabama’s First City, edited by Michael V. R. Thomason. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.