John Allan Wyeth

John Allan Wyeth (1845-1922) served in the Confederate Army as a youth and would go on to become a leading New York surgeon, the developer of improved surgical procedures, and the author of medical texts and a variety of other works. As the founder of the first post-graduate medical school in the United States, the New York Polyclinic Graduate Medical School and Hospital, he significantly influenced medical education and the practice of medicine in the United States.

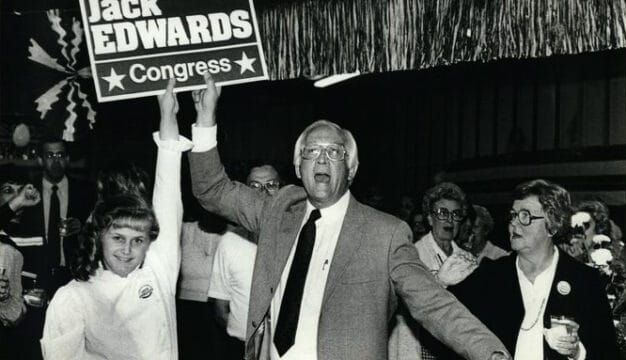

John Allan Wyeth, 1914

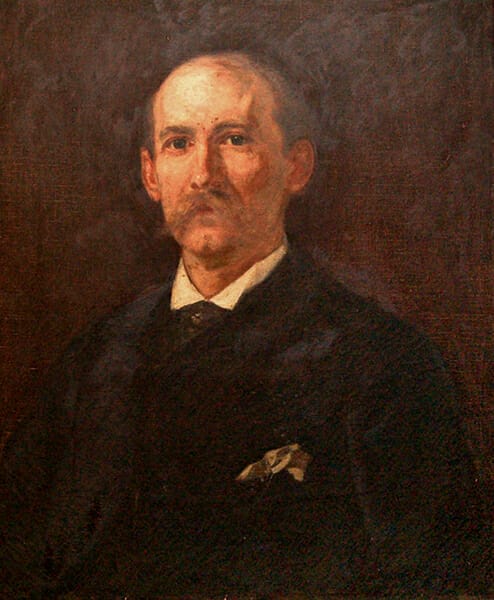

Wyeth was born May 26, 1845, in Guntersville, Marshall County, to Louis and Euphemia Allan Wyeth and had two older sisters. John’s father came from a distinguished family that included George Wythe, a signer of the Declaration of Independence from Virginia. Louis was a newly licensed lawyer, from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, when he came to Alabama. He soon became a county judge and married Euphemia Allan, daughter of the John Allan, a Presbyterian minister in nearby Huntsville who was also an ardent emancipationist. Louis, in 1848, established Guntersville as the seat of Marshall County, funded construction of a courthouse and school, and was elected to the state legislature. John Allan Wyeth grew up in a rural and largely unsettled area bordering the Tennessee River, although his family made frequent visits to the cultural center that was Huntsville. At age 15, he enrolled at La Grange Military Academy in Colbert County.

John Allan Wyeth, 1914

Wyeth was born May 26, 1845, in Guntersville, Marshall County, to Louis and Euphemia Allan Wyeth and had two older sisters. John’s father came from a distinguished family that included George Wythe, a signer of the Declaration of Independence from Virginia. Louis was a newly licensed lawyer, from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, when he came to Alabama. He soon became a county judge and married Euphemia Allan, daughter of the John Allan, a Presbyterian minister in nearby Huntsville who was also an ardent emancipationist. Louis, in 1848, established Guntersville as the seat of Marshall County, funded construction of a courthouse and school, and was elected to the state legislature. John Allan Wyeth grew up in a rural and largely unsettled area bordering the Tennessee River, although his family made frequent visits to the cultural center that was Huntsville. At age 15, he enrolled at La Grange Military Academy in Colbert County.

Young John Wyeth

Louis Wyeth was a delegate to the Alabama Secession Convention on January 7, 1861, and voted against secession. However, the Ordinance of Secession passed on January 11, and Alabama joined the Confederate States of America. After that, the military academy closed and the faculty and older cadets went off to fight for the Confederacy in the Civil War. In the fall of 1862, John Wyeth joined Gen. John Hunt Morgan‘s irregular Confederate cavalry unit, “Morgan’s Raiders,” serving until early 1863, when he joined the 4th Alabama Cavalry as a private. He served under Gen. Joseph Wheeler, fighting in several harrowing engagements in Tennessee, most notably the Battle of Chickamauga. In early October 1863, he was captured, developed a severe case of pneumonia, and was taken by train as a prisoner of war to severely overcrowded Camp Morton, near Indianapolis, Indiana. Wyeth would later describe the camp’s conditions in his autobiography as “wholly inadequate” during his 16 months there, having insufficient shelter and food and a lack of blankets, particularly during the unusually cold winter in 1864-65. Prisoners sometimes starved or froze to death, and Wyeth contracted various diseases and suffered from their effects for many years afterwards. Connections to relatives in Illinois provided him some much-needed clothing, books, and money used to purchase extra rations. Wyeth, fearing a charge of desertion, turned down an offer of parole procured by one Illinois relative who had practiced law in the same circuit as Abraham Lincoln. A kind camp physician kept Wyeth alive in the infirmary; considered unable to fight, he was included in a prisoner exchange in February 1865. Back in Guntersville, he helped rebuild his family’s burned-out home and continued to recover, resolving to become a doctor himself.

Young John Wyeth

Louis Wyeth was a delegate to the Alabama Secession Convention on January 7, 1861, and voted against secession. However, the Ordinance of Secession passed on January 11, and Alabama joined the Confederate States of America. After that, the military academy closed and the faculty and older cadets went off to fight for the Confederacy in the Civil War. In the fall of 1862, John Wyeth joined Gen. John Hunt Morgan‘s irregular Confederate cavalry unit, “Morgan’s Raiders,” serving until early 1863, when he joined the 4th Alabama Cavalry as a private. He served under Gen. Joseph Wheeler, fighting in several harrowing engagements in Tennessee, most notably the Battle of Chickamauga. In early October 1863, he was captured, developed a severe case of pneumonia, and was taken by train as a prisoner of war to severely overcrowded Camp Morton, near Indianapolis, Indiana. Wyeth would later describe the camp’s conditions in his autobiography as “wholly inadequate” during his 16 months there, having insufficient shelter and food and a lack of blankets, particularly during the unusually cold winter in 1864-65. Prisoners sometimes starved or froze to death, and Wyeth contracted various diseases and suffered from their effects for many years afterwards. Connections to relatives in Illinois provided him some much-needed clothing, books, and money used to purchase extra rations. Wyeth, fearing a charge of desertion, turned down an offer of parole procured by one Illinois relative who had practiced law in the same circuit as Abraham Lincoln. A kind camp physician kept Wyeth alive in the infirmary; considered unable to fight, he was included in a prisoner exchange in February 1865. Back in Guntersville, he helped rebuild his family’s burned-out home and continued to recover, resolving to become a doctor himself.

Wyeth enrolled at Kentucky’s University of Louisville medical school, which required no preliminary college or entrance examination and offered the typical training of two terms of seven months each of lectures on physiology, surgery, medicine, obstetrics, chemistry, and homeopathy. Anatomy was the most thoroughly taught subject and involved some dissecting, but otherwise medical education involved no laboratory work, no practical demonstrations, and no interaction with patients. Upon graduation in 1869, Wyeth returned to Guntersville but quickly realized how incomplete his training had been and closed his practice after six weeks. He decided to pursue further study and took a series of farm and riverboat jobs in Arkansas for the next three years to earn money for tuition.

Arriving in New York in 1872, he was surprised and disappointed that the city’s three medical schools offered no special courses for graduates. He enrolled at Bellevue Hospital Medical College and attended lectures and clinics in surgery and received another degree in 1873. To prepare for a career as a surgeon, he also taught himself to be ambidextrous. His expertise in anatomy led to a staff appointment at Bellevue, where he would establish the first pathology lab in the city, conveniently located over the morgue, where he dissected cadavers for two years. He learned French and German so he could read medical journals in those languages and began to submit his own prize-winning articles on improving surgical procedures that were acclaimed by experts for their life-saving innovations.

Wyeth became convinced that American medical schools’ reliance upon theoretical training did not prepare future doctors sufficiently for their practices. Instead, he envisioned training under a faculty of experts providing practical guidance. In 1878, he went abroad to Europe and studied the superior training of physicians from the best schools there for two years. In Paris, he met and was encouraged in his studies by physician J. Marion Sims, a friend of his father’s from Montgomery. Sims was a leading New York surgeon and was responsible for a number of innovations in the field of gynecology; he was much in demand by members of the royal families of Europe. Through Sims, Wyeth met leading physicians and surgeons in Paris, London, Berlin, and Vienna, who instructed him in their methods of medical practice.

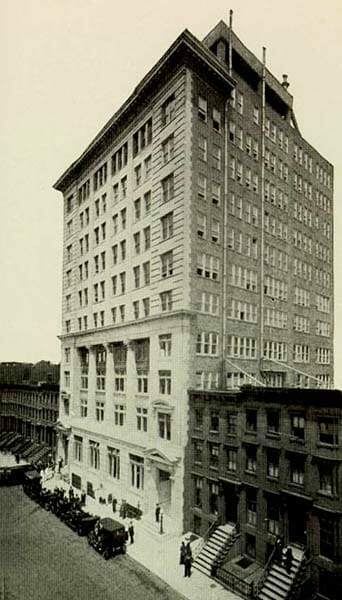

New York Polyclinic

Wyeth returned to New York in 1880, took up appointments as a visiting surgeon at both St. Elizabeth’s and Mount Sinai hospitals, and became recognized as one of the most prominent surgeons in the city. He was admired by his colleagues as much for his character and his calm demeanor as for his surgical expertise. He soon built a successful private practice and then worked to fulfill his dream of creating the New York Polyclinic Graduate Medical School and Hospital. This latter project drew upon all his expertise, intelligence, energy, and charisma to gather a board of directors, donors, and faculty of prominent New York medical specialists who were willing both to teach the students and treat the patients in the Polyclinic Hospital for free. (Until the hospital closed in 1975, the façade of the 12-story structure bore the motto “For the Sick Without Regard to Race or Class.”)

New York Polyclinic

Wyeth returned to New York in 1880, took up appointments as a visiting surgeon at both St. Elizabeth’s and Mount Sinai hospitals, and became recognized as one of the most prominent surgeons in the city. He was admired by his colleagues as much for his character and his calm demeanor as for his surgical expertise. He soon built a successful private practice and then worked to fulfill his dream of creating the New York Polyclinic Graduate Medical School and Hospital. This latter project drew upon all his expertise, intelligence, energy, and charisma to gather a board of directors, donors, and faculty of prominent New York medical specialists who were willing both to teach the students and treat the patients in the Polyclinic Hospital for free. (Until the hospital closed in 1975, the façade of the 12-story structure bore the motto “For the Sick Without Regard to Race or Class.”)

When the facility opened in 1881, it attracted medical practitioners who already had an undergraduate degree and the standard two years of lectures in a medical college but desired more thorough practical training. The Polyclinic offered this in a third and fourth year of hands-on postgraduate instruction that went beyond the merely theoretical, offering them demonstration classes in what their basic medical school training had failed to provide.

Among those in the first classes were brothers William J. Mayo and Charles Horace Mayo, who would later establish the famed Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. The Polyclinic’s success led other top medical schools to follow its lead and institute additional courses of a more practical nature in third- and fourth-year curriculums. (In 1918, the Polyclinic Graduate Medical School was absorbed by Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons) On April 10, 1886, Wyeth married Florence Nightingale Sims, daughter of J. Marion Sims, whom he had met while in Europe; the couple would have two sons and one daughter.

Wyeth Statue

Wyeth wrote innovative and widely used medical texts that introduced illustrations in color as well as a memoir, With Sabre and Scalpel: The Autobiography of a Soldier and Surgeon; an acclaimed biography, That Devil Forrest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest, and many magazine articles. His honors included being elected president of the New York Academy of Medicine in 1906 and 1908 and the president of the American Medical Association in 1902; he received honorary doctorates from the University of Alabama in 1900 and the University of Maryland in 1908. Wyeth’s wife died in 1915; in 1918, he married Marguerite Chalifoux in the Polyclinic Hospital while recovering from a broken ankle. He died of a heart attack on May 22, 1922, and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Wyeth Statue

Wyeth wrote innovative and widely used medical texts that introduced illustrations in color as well as a memoir, With Sabre and Scalpel: The Autobiography of a Soldier and Surgeon; an acclaimed biography, That Devil Forrest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest, and many magazine articles. His honors included being elected president of the New York Academy of Medicine in 1906 and 1908 and the president of the American Medical Association in 1902; he received honorary doctorates from the University of Alabama in 1900 and the University of Maryland in 1908. Wyeth’s wife died in 1915; in 1918, he married Marguerite Chalifoux in the Polyclinic Hospital while recovering from a broken ankle. He died of a heart attack on May 22, 1922, and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Additional Resources

Enos, John S., M.D. “Tribute to ‘Master Surgeon’ and Founder of Polyclinic Medical School.” The New York Times, June 4, 1922.

Flexner, Abraham. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Bulletin Number Four. 1910. Reprint, New York: Carnegie Foundation, 1972.

Hartshorn, Winfred Morgan. History of the New York Polyclinic Medical School and Hospital. New York: The Haddon Craftsmen, Inc., 1942