Civil War Journalism in Alabama

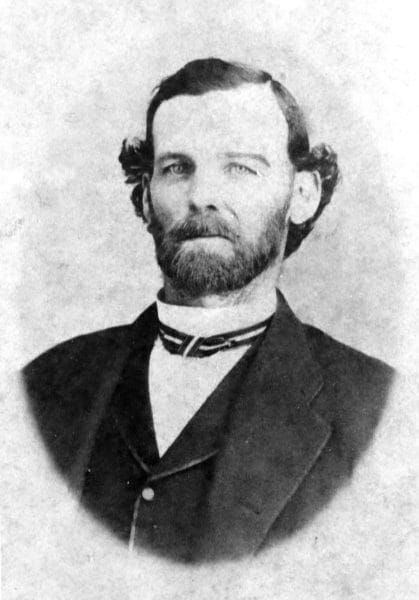

John Forsyth Jr.

By the time of the Civil War, newspapers in Alabama had come to occupy an important role as providers of news and opinion. More than 50 newspapers were published in the state, the vast majority weeklies. Virtually every community of any size in the state had at least one and, in many cases, two newspapers. The growth of the press was fueled in part by the debate over the future of slavery, as many editors began publishing papers in order to shape public opinion.

John Forsyth Jr.

By the time of the Civil War, newspapers in Alabama had come to occupy an important role as providers of news and opinion. More than 50 newspapers were published in the state, the vast majority weeklies. Virtually every community of any size in the state had at least one and, in many cases, two newspapers. The growth of the press was fueled in part by the debate over the future of slavery, as many editors began publishing papers in order to shape public opinion.

The editorial staffs of the state’s newspapers varied according to the size of the publication. The weekly editor had to be a true “jack-of-all-trades” because he had to write the paper’s news stories and editorials, sell advertising, keep the financial records, and help with printing and circulation. Daily editors generally employed one or two assistant editors who helped with newsgathering, editorial writing, and other tasks. The typical daily or weekly newspaper in the state was four pages. The first page contained features such as fiction and poetry as well as a large amount of advertising. The second and third pages were devoted to news, editorials, letters, and commercial reports. These pages also contained advertising, much of it for legal firms and services. Page four was devoted almost entirely to advertising.

Like other newspapers across the South, Alabama’s press was divided on the issue of secession. Many publications were squarely in the secession camp. The Southern Champion in Claiborne, Monroe County, declared: “A Southern or Gulf Confederacy is our motto.” But others opposed disunion for various reasons. The Montgomery Confederation, for instance, warned: “Just go ahead with your shouts and huzzas for disunion and revolution one month longer, and then you will have something to complain of.”

After Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency in 1860, however, many newspapers shifted their editorial stance. Like their brethren across much of the South, the state’s editors saw the magnitude of Lincoln’s victory in the North as an ominous sign. The future of slavery, many believed, was in jeopardy. Some defenders of the Union promptly became sharp critics. The editors of the Confederation, who had once called secession “treason,” reversed their stance and said they hoped that “the day is not far distant” when the South would leave “such an obnoxious and oppressive government.” Other Unionist newspapers ceased printing rather than support Alabama’s secession or openly support the Union. The editor of the Union Banner in Athens, Limestone County, for instance, reported that despite being located in the state’s largest area of Union support, he could not continue publishing the paper.

Once the war began, Alabama’s newspapers tried to report on events and issues as best they could, using a variety of news sources, including correspondents and wire services. On April 19, 1861, telegraphic services provided by the American Telegraphic Company in Washington, D.C., were taken over by the U.S. Army and other telegraph lines elsewhere were later severed, ending Associated Press service. To fill the void, the Press Association of the Confederate States of America, a cooperative news gathering agency, was created in March 1863 by John S. Thrasher at the behest of southern editors. The Press Association distributed news via telegraph to member newspapers across the Confederacy. The majority of its dispatches were about the war, but they also included items about Richmond and other locations in the Confederacy. Newspapers also tried their best to get the news to readers as quickly as possible. The latest news was posted outside newspapers offices and the largest publications sometimes printed “extra” editions.

Journalists during the war were in no way objective. Moreover, in an era when news and opinion often mixed, correspondents regularly injected their personal views, prejudices, and patriotic sentiments into stories. But the most honest reporters did not ignore problems with the military or the administration of the war when they became apparent. Only the state’s largest newspapers, however, could afford to hire full-time correspondents to report on the fighting. William G. Shepardson, a physician with the Confederate Army, served as a correspondent for the Mobile Advertiser and Register. He reported all four years of the war, initially on land battles and later on the fighting at sea, spending time on board the notorious Confederate cruiser Tallahassee and writing about the raider’s seizure of numerous U.S. Navy vessels in 1864. Peter W. Alexander of Savannah, Georgia, also reported for the Advertiser and Register, among other newspapers. Alexander covered many of the major battles, including First Bull Run, Shiloh, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and Chattanooga. His reporting was recognized for its accuracy and detail. He also wrote stories that highlighted difficulties within the army, medical department, and quartermaster corps.

Far more often, however, the state’s newspapers published letters from “soldier correspondents.” Editors recognized that readers wanted news from regiments comprised of hometown men. So they made arrangements with a member of a local unit, often an officer, to send back letters to the newspaper with news of the war. Going by pen names such as “Private,” “Buttermilk,” and “Ready,” some correspondents sent letters only occasionally, but others sent regular correspondence for months.

Like the rest of the Confederate press, Alabama newspapers were hampered during the war by constant shortages of materials, including paper, ink, and metal type. As a result, virtually every publication reduced its size and the number of pages in each issue. The papers also were hurt by the loss of large numbers of employees who enlisted in the Confederate Army. Even though they could justly claim a military exemption, dozens of employees chose to fight, including some editors. John Seibels, the editor of the Confederation and an officer in the Mexican War, helped organize the Sixth Alabama Infantry and served as a colonel in the regiment. By the end of the war, only about 20 newspapers were still being published.

Alabama became home to two “refugee” newspapers, the Chattanooga Rebel and Memphis Appeal, which had been forced to move when their cities were captured by the U.S. Army. The Rebel moved twice before settling in Selma in 1865. It was captured when Selma was overtaken by federal troops in the closing weeks of the war. The Appeal, which relocated so often that it became known as the “Moving Appeal,” was published in Montgomery for several months in late 1864 and early 1865. Its presses and supplies were captured in Columbus, Georgia, in the last month of the war.

By late 1864, some Alabama editors were publicly admitting that prospects for a Confederate victory looked bleak. The editor of the Montgomery Mail declared that without “Providential interference, which seemed unlikely, the South could not prevail. It would be wicked to deceive ourselves,” he wrote, and “unwise to deny the truth to ourselves.” But others insisted that the Confederacy would prevail. After returning to Mobile from Richmond in December 1864, Advertiser and Register editor John Forsyth boasted that Gen. Robert E. Lee was “the master of the city’s defenses.” He also claimed that the U.S. Army was “powerless beyond the Confederate entrenchments.”

Although Alabama was not the scene of much fighting, in the final weeks of the war several newspapers in the state were taken over by federal forces. Forsyth and other employees of the Advertiser and Register fled just ahead of the U.S. Army’s occupation of Mobile, taking with them four presses and all the ink and paper they could carry. The Army confiscated the office and began publishing a new paper, the Mobile Daily News, using the equipment left behind. It is not known how many issues of the Daily News were published, but by July, Forsyth was back in Mobile publishing the Advertiser and Register.

After the war, editors in Alabama had to sign a loyalty oath agreeing to “faithfully defend” the Constitution of the United States. By the fall, most newspapers were publishing again and beginning to report on another tumultuous period in the state’s history, Reconstruction.

Additional Resources

Andrews, J. Cutler. The South Reports the Civil War. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1970.

Burnett, Lonnie A. The Pen Makes a Good Sword: John Forsyth of the Mobile Register. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.

Reynolds, Donald E. Editors Make War: Southern Newspapers in the Secession Crisis. Nashville, Tenn.: Vanderbilt University Press, 1966.

Risley, Ford. Civil War Journalism. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger, 2012.