Charlie Lucas

Lucas, Charlie

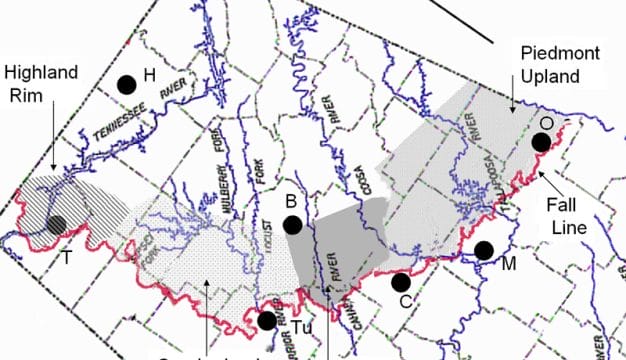

The work of self-taught artist Charlie Lucas (1951- ) draws from both the people and the land of Alabama’s Black Belt region and from the iron and steel industry of the Birmingham District. From his earliest experiments with scraps of iron and steel, Lucas searched for meaning and images in cast-off material and began to envision completed works in piles of junk objects or remnants of raw materials. He assembles such fragments mentally before he physically welds, twists, and bolts them together to become portraits of people and animals—brought to life by the narratives he weaves around them. He is often included in the group of self-taught artists who create what is termed “outsider art” for their lack of formal training and for their shared focus on their immediate surroundings, personal experiences, and inner visions. Some artists so labeled reject those terms and wish to simply be called “artists.”

Lucas, Charlie

The work of self-taught artist Charlie Lucas (1951- ) draws from both the people and the land of Alabama’s Black Belt region and from the iron and steel industry of the Birmingham District. From his earliest experiments with scraps of iron and steel, Lucas searched for meaning and images in cast-off material and began to envision completed works in piles of junk objects or remnants of raw materials. He assembles such fragments mentally before he physically welds, twists, and bolts them together to become portraits of people and animals—brought to life by the narratives he weaves around them. He is often included in the group of self-taught artists who create what is termed “outsider art” for their lack of formal training and for their shared focus on their immediate surroundings, personal experiences, and inner visions. Some artists so labeled reject those terms and wish to simply be called “artists.”

Born in Birmingham on October 12, 1951, and raised in rural Elmore County north of Montgomery, Lucas was one of 14 children born into a sharecropping family. His father often worked in Birmingham as a chauffeur and car mechanic. Because the family frequently needed his help on their small farm, Lucas often missed school. Yet he was surrounded by an extended family of skilled craftspeople—blacksmiths, auto mechanics, quilters, and basket makers who provided the education that would serve him later in his creative life. His great-grandfather, Cain Jackson, exposed Lucas to metalworking at a very young age, allowing Lucas to use his tools and materials to make his own trinkets. Although it would be several years before he took up metalwork as art, Lucas’s feel for the medium was forged in that workshop.

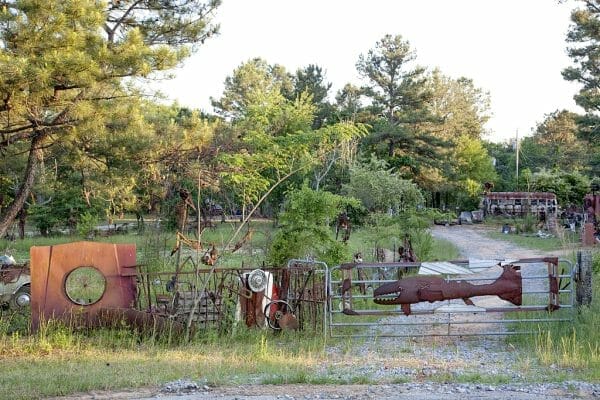

Former Charlie Lucas Workshop

Lucas’s struggles with formal education and his severe dyslexia led him to drop out of school at the age of 14 and leave his family. He travelled around the Southeast for the next five years, doing odd jobs such as picking oranges in Florida. During a visit home, Lucas proposed to Annie Lykes, whom he had known since childhood, and the two moved back to Florida, where they married. The couple returned to Alabama in 1971 and settled on the family’s 40-acre farm in the community of Pink Lily in Autauga County, where they would raise six children.

Former Charlie Lucas Workshop

Lucas’s struggles with formal education and his severe dyslexia led him to drop out of school at the age of 14 and leave his family. He travelled around the Southeast for the next five years, doing odd jobs such as picking oranges in Florida. During a visit home, Lucas proposed to Annie Lykes, whom he had known since childhood, and the two moved back to Florida, where they married. The couple returned to Alabama in 1971 and settled on the family’s 40-acre farm in the community of Pink Lily in Autauga County, where they would raise six children.

During this time, he worked on the farm and at odd jobs in the area, until he took a maintenance job at a local hospital in the late 1970s. He began to dabble in art during this period but did not turn to it full time until he suffered an accident in 1984. Lucas seriously injured his back while loading timber on a truck and had to undergo surgery and a long convalescence. Confined to a bed and unable to work, Lucas appealed to God to be given an ability or talent that no else had. He believes that he was then given a revelation from which was born his devotion to art. In particular, he returned to the metals with which he had become so familiar in his great-grandfather’s blacksmith shop.

Caveman

Lucas began displaying his figural sculptures made from twisted wire and other metal junk around his yard in Pink Lily, and they attracted a stream of curious visitors and began to draw the interest of the professional art world. He soon became known as “Tin Man” in part for his metal sculptures, although Lucas insists the name mostly comes from the fact that he had little money during his early years as an artist, with only 10 (“tin”) dollars in his pocket. In the late 1980s, he began selling his assemblages and paintings to collectors, galleries, and museums. In 1988, he had his first exhibition at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta in its survey of contemporary folk art, Outside the Mainstream: Folk Art in Our Time. As his work began appearing in museum exhibitions and publications on contemporary American folk artists, he joined other Alabama artists such as Bill Traylor, Mose Tolliver, and Jimmy Lee Sudduth in benefiting from the genre’s growing public appreciation and market appeal.

Caveman

Lucas began displaying his figural sculptures made from twisted wire and other metal junk around his yard in Pink Lily, and they attracted a stream of curious visitors and began to draw the interest of the professional art world. He soon became known as “Tin Man” in part for his metal sculptures, although Lucas insists the name mostly comes from the fact that he had little money during his early years as an artist, with only 10 (“tin”) dollars in his pocket. In the late 1980s, he began selling his assemblages and paintings to collectors, galleries, and museums. In 1988, he had his first exhibition at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta in its survey of contemporary folk art, Outside the Mainstream: Folk Art in Our Time. As his work began appearing in museum exhibitions and publications on contemporary American folk artists, he joined other Alabama artists such as Bill Traylor, Mose Tolliver, and Jimmy Lee Sudduth in benefiting from the genre’s growing public appreciation and market appeal.

The Valve Man

Lucas’s sculptures typically are made from cast-off pieces of iron, steel, wood, and other materials. The Valve Man, for example, is made from the wheels and springs that form the parts that release pressure through the valves in an engine, and the figure’s relaxed appearance reflects the purpose of the items from which it is made. The figures in Spirits on the Door, created from hubcaps and sheet metal, appear trapped in a state of limbo, floating uneasily across Lucas’s wooden door “canvas” but tethered by rope and garden hose to the earth they cannot escape. Husband and Wife is an unbalanced couple: one figure (the husband?) is bound with wire and metal brackets, and the other (the wife?) is free of any such encumbrances. The viewer is encouraged to wonder if the work depicts an imminent breakup or a couple simply coexisting in uneasy tension. Lucas speaks freely about what he had in mind when creating his works—especially portraits that depict family members or people he knows—but he also appreciates that viewers compose their own stories. Lucas’s willingness to defer to others’ perspectives has made him an especially effective workshop leader for children.

The Valve Man

Lucas’s sculptures typically are made from cast-off pieces of iron, steel, wood, and other materials. The Valve Man, for example, is made from the wheels and springs that form the parts that release pressure through the valves in an engine, and the figure’s relaxed appearance reflects the purpose of the items from which it is made. The figures in Spirits on the Door, created from hubcaps and sheet metal, appear trapped in a state of limbo, floating uneasily across Lucas’s wooden door “canvas” but tethered by rope and garden hose to the earth they cannot escape. Husband and Wife is an unbalanced couple: one figure (the husband?) is bound with wire and metal brackets, and the other (the wife?) is free of any such encumbrances. The viewer is encouraged to wonder if the work depicts an imminent breakup or a couple simply coexisting in uneasy tension. Lucas speaks freely about what he had in mind when creating his works—especially portraits that depict family members or people he knows—but he also appreciates that viewers compose their own stories. Lucas’s willingness to defer to others’ perspectives has made him an especially effective workshop leader for children.

The Dancing Shoe

By the late 1980s, Lucas had added painting—mostly using ordinary house paint—to his ever-increasing assortment of daily artistic productions. Some of the paintings, such as The Dancing Shoe, express his love of color and the simple joy of the brush’s movement across his “canvas” of cardboard or plywood. Paintings in this vein are strikingly reminiscent of the works of European twentieth-century painters Wassily Kandinsky or Joan Miró. Other works, such as Caveman, are notable for their depictions of animals and human faces—themes that can be found recurring in both his sculptures and his paintings. These works display elements that relate to the European schools of Expressionism and Cubism.

The Dancing Shoe

By the late 1980s, Lucas had added painting—mostly using ordinary house paint—to his ever-increasing assortment of daily artistic productions. Some of the paintings, such as The Dancing Shoe, express his love of color and the simple joy of the brush’s movement across his “canvas” of cardboard or plywood. Paintings in this vein are strikingly reminiscent of the works of European twentieth-century painters Wassily Kandinsky or Joan Miró. Other works, such as Caveman, are notable for their depictions of animals and human faces—themes that can be found recurring in both his sculptures and his paintings. These works display elements that relate to the European schools of Expressionism and Cubism.

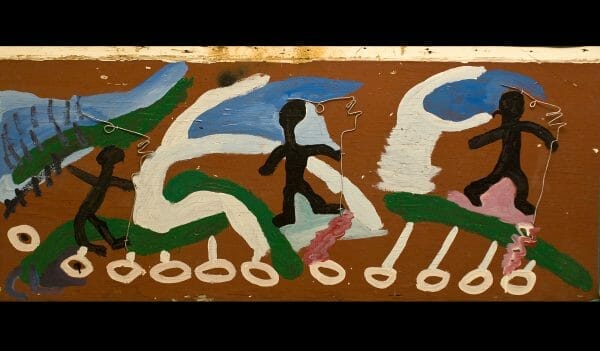

Lucas also combines sculpture and painting in a variety of collages, as in Ancestors Keeping the Path Open, Moanin’ and Groanin’. The piece is part of a series of large works that focus on the theme of slavery and the Middle Passage. The works are broadly horizontal, thus allowing Lucas to depict the slave ship with its many captives. He makes his own frames from whatever materials he can find (including rubber garden hoses), or from existing art frames that friends have given him.

Spirits on the Way

In 2000, Lucas travelled to France in the company of Alabama artist Nall for an artist’s residency and tour that also took him to Italy. He has travelled across America as well exhibiting his art, giving talks and interviews, and conducting workshops for students of all ages. His work has appeared in solo and group exhibitions at the New Orleans Museum of Art, Birmingham Museum of Art, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and Rosa Parks Museum and Library at Troy University-Montgomery.

Spirits on the Way

In 2000, Lucas travelled to France in the company of Alabama artist Nall for an artist’s residency and tour that also took him to Italy. He has travelled across America as well exhibiting his art, giving talks and interviews, and conducting workshops for students of all ages. His work has appeared in solo and group exhibitions at the New Orleans Museum of Art, Birmingham Museum of Art, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and Rosa Parks Museum and Library at Troy University-Montgomery.

In 2004, Lucas relocated from Pink Lily to Selma and lived next door to long-time friend and storyteller and journalist Kathryn Tucker Windham until her death in 2011. He continues to live in the same house today but creates his artworks in a large warehouse in downtown Selma, which serves as a gallery, studio, storage space for his raw materials, and garage for his hand-painted Ford Mustang and other vehicles. He opens his studio/gallery to visitors regularly.

Further Reading

- Lucas, Charlie, and Ben Windham. Charlie Lucas: Tin Man. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2009.

- Trechsel, Gail Andrews, ed. Pictured in My Mind: Contemporary American Self-Taught Art. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Museum of Art, 1995.

- Yelen, Alice Rae. Passionate Visions of the American South: Self-Taught Artists from 1940 to the Present. New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art, 1993.