Alabama Fever

The opening of present-day Alabama to settlement when the Creek War of 1813-14 ended inspired a wave of migration from the eastern United States that foreshadowed the large-scale westward movement of later decades. “Alabama Fever,” an expression in use by 1817, referred to the frenzy to establish land claims in the area formerly known as West Florida or East Mississippi, which resulted in the admission of Alabama as a state by 1819. The driving force behind Alabama Fever was the global demand for cotton cultivation stimulated by new industrial textile manufacturing processes. The expression “Alabama Fever” has also been used by historians to describe the broader phenomenon of the expansion of the cotton frontier before 1860, from the seaboard states to Alabama and Mississippi and onward to northern Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas. The establishment of cotton plantations in Alabama and the region as a whole transformed and expanded the global economy, producing unprecedented wealth in combination with the northern and European textile industry. In political terms, the emergence of the Deep South as an economic force increased the clout of slave states in the federal government, intensifying the hostilities that resulted in the Civil War.

Alabama Fever resulted from global economic forces that accelerated the drive to colonize the area initially known as East Mississippi. Great Britain’s commercial interests in India beginning in the 1600s introduced Europeans to eastern cotton textiles such as calico, madras, and khaki. By the late 1700s, English textile machinery had been adapted to produce high-quality versions that earned great profits and rapidly transformed the consumer market. The invention of an industrial cotton gin capable of removing seeds allowed planters to supply short-staple cotton, a faster-growing variety of the plant, to British and New England manufacturers. Quickly, the cotton industry emerged as vital to the U.S. economy. Cotton cultivation, however, rapidly exhausts the soil; within 30 years, cotton yields in Georgia and the Carolinas had diminished, prompting planters to seek more fertile fields.

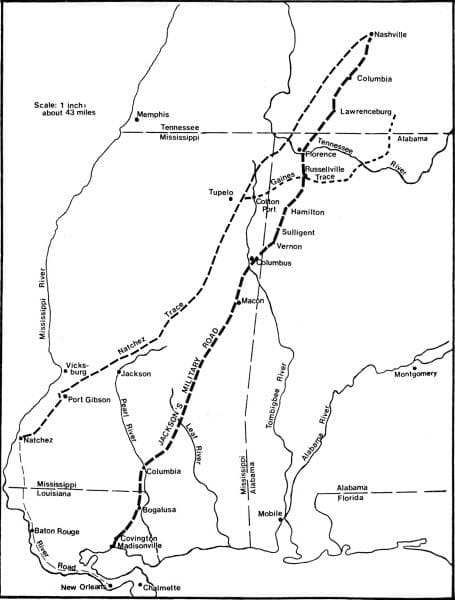

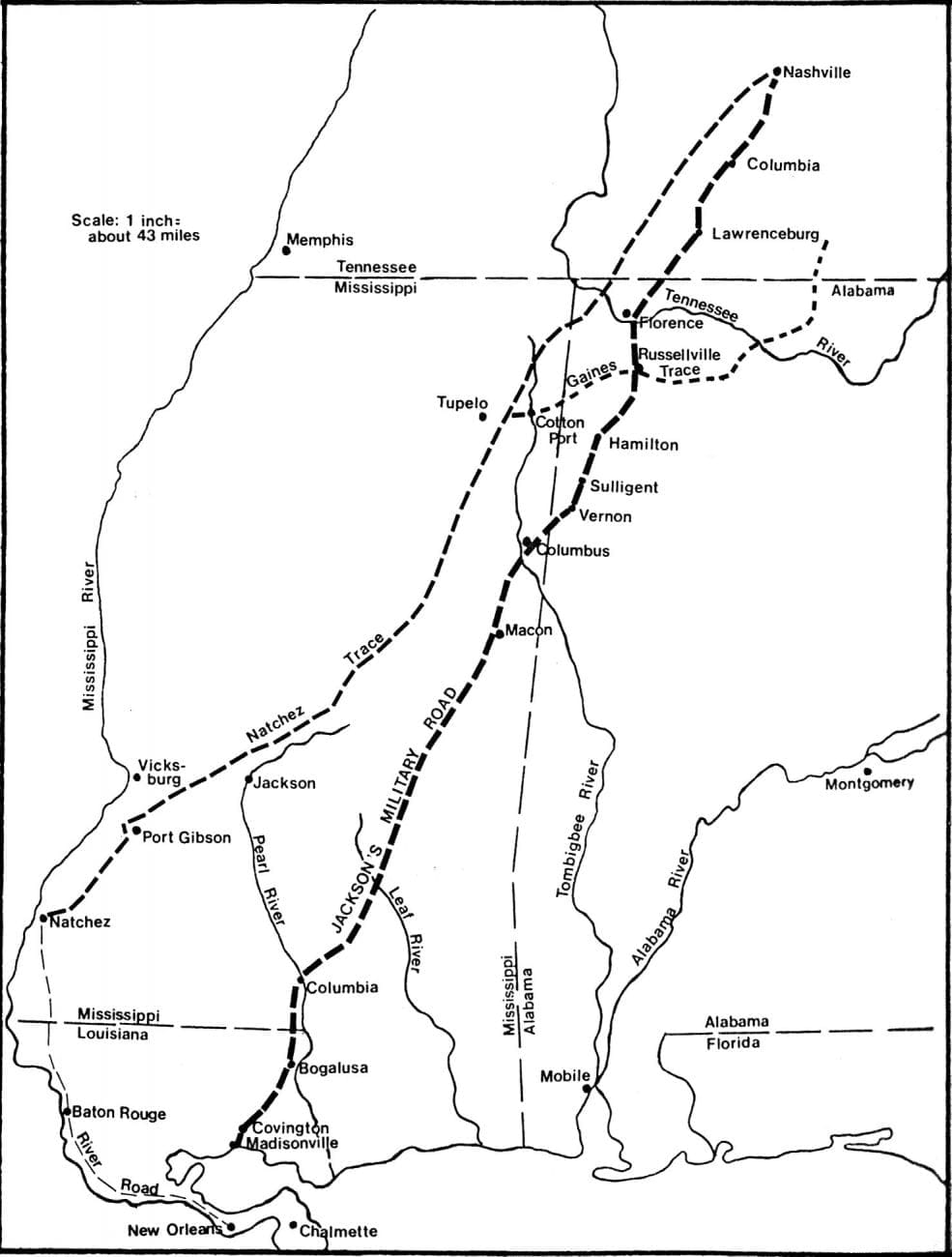

Alabama, however, had largely been under control of several large Indian tribes, including the Cherokees, Choctaws, and groups within the Creek Confederacy prior to the War of 1812. The decisive defeat of the Creeks and the British by Gen. Andrew Jackson in 1814 and the acquisition of just over 21 million acres of land under the Treaty of Fort Jackson inaugurated the era of Alabama Fever in earnest. Jackson led efforts to open the new territory to settlement and infrastructure, ordering the construction of a military road from Muscle Shoals, where he purchased property for himself, to the Gulf of Mexico. He also urged the General Land Office to quickly survey and sell the land acquired from the Creeks. Another major point of entry was the Federal Road, which ran within the state from roughly present-day Phenix City to Mobile. A network of lesser roads and Indian trails connected Alabama to Georgia, Tennessee, and the western Carolinas.

Land sales combined with the formalization of squatter claims swelled the settled portion of the Alabama lands. In 1810, the population of Alabama was estimated as being under 10,000; by 1820, that number had risen to more than 127,000 and by 1830 had topped 300,000. The population continued to increase, so that by 1860 it was just short of one million. Early population centers emerged around Huntsville in the north, which conducted its first census in 1810 and was home to some 260 brick houses by early 1818, including some two and three stories high. At the same time, a number of fledgling towns such as Selma, Montgomery, and Marion were established in the Black Belt, where the dark soil proved excellent for cotton cultivation. More than 2.25 million acres were sold in 1819, the year Alabama successfully petitioned for statehood.

Early Alabamians demonstrated what observers would describe as the characteristic mania of the Alabama Fever, in which planters sold cotton to buy more slaves to produce more cotton, meanwhile always acquiring new acreage to maximize output. Roughly one third of the migrants were slaves, about 40,000 of whom were moved to the new state between 1810 and 1820. Alabama Fever thus greatly expanded the institution of slavery, allowing established holders to profit not only from cotton production but also from the sale and relocation of enslaved people for labor and reproduction. Beginning in the early nineteenth century, a significant number of the enslaved would be relocated more than once, to Alabama then to parts farther west, as dwindling cotton yields continually expanded the frontier.

By the 1860s, the domestic slave trade fueled by Alabama Fever and its western variations had resulted in the forced migration of at least 875,000 persons. As many as 435,000 slaves labored in Alabama by this time. Facing geographic and political constraints, cotton magnates had turned their attention to the possible conquest and annexation of territory in the Caribbean and Central America. The global appetite for cotton only escalated as textile manufacturing and global consumer demand continued to grow. The outbreak of the Civil War and the destruction of the slave economy finally checked the advance of Alabama Fever in the southern states, but the society, traditions, and physical landscape that it shaped persist in Alabama and the region to the present.

Further Reading

- Dattel, Eugene R. Cotton and Race in the Making of America: The Human Costs of Economic Power. Washington, D.C.: Government Institutes Press, 2009.

- Libby, David J. Slavery and Frontier Mississippi, 1720-1835. Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2008.

- Richmond, Robert W. A Nation Moving West: Readings in the History of the American Frontier. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966.