Neighborhood Organized Workers of Mobile

The Neighborhood Organized Workers (NOW) was a civil and economic rights organization founded in Mobile during the late 1960s and early 1970s. NOW organized mass marches, boycotts, and large public protests to lobby for its goals of economic improvement in Mobile’s black communities and greater minority representation in local politics. At its height, the multiracial organization boasted several hundred members.

NOW March, 1968

During the summer of 1966, several civil rights activists began meeting informally in the home of Dorothy Williams, a well-known activist in the area who had previously attempted to establish a branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Mobile. The group decided to form a new organization, which they conceived initially as an effort to mobilize neighborhood cleanup projects and promote “human dignity” through economic improvement. David Underhill, a white reporter for the Southern Courier, a Montgomery-based civil rights newspaper, suggested the name Neighborhood Organized Workers. David Jacobs, a local educator, was elected the first president, and the organization began to lobby Mobile politicians on behalf of the black residents who lived in areas targeted for urban renewal projects.

NOW March, 1968

During the summer of 1966, several civil rights activists began meeting informally in the home of Dorothy Williams, a well-known activist in the area who had previously attempted to establish a branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Mobile. The group decided to form a new organization, which they conceived initially as an effort to mobilize neighborhood cleanup projects and promote “human dignity” through economic improvement. David Underhill, a white reporter for the Southern Courier, a Montgomery-based civil rights newspaper, suggested the name Neighborhood Organized Workers. David Jacobs, a local educator, was elected the first president, and the organization began to lobby Mobile politicians on behalf of the black residents who lived in areas targeted for urban renewal projects.

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, prompted the first major confrontation between NOW and Mobile politicians. After King’s death, NOW petitioned the city for a permit to hold a memorial march. The city denied the request and also instituted a curfew, hoping perhaps to avoid the type of violent outbreaks occurring in other cities. On April 7, 1968, NOW marched through the city without a permit, led by members Jerry Pogue and James Dixon, who walked slowly ahead of the marchers carrying the American and Christian flags. By the time they reached the city auditorium, some two miles later, an estimated 7,000 supporters, white and black, had joined in the solemn march. It was the first mass march in the city’s history, and it set the stage for even greater confrontations between NOW and Mobile’s white leaders.

The march transformed NOW from an economic improvement organization into a vehicle for direct-action protest. This shift in mission became even clearer when David Jacobs was replaced as president by Noble Beasley, a Mississippi native who owned a nightclub on the outskirts of the city and who embraced a more militant philosophy than did Jacobs. Soon after the shift in leadership, NOW began picketing school board meetings and organized an economic boycott of downtown businesses for the Christmas season. In June 1968, NOW announced a boycott of the recently opened Mobile Municipal Auditorium as a way of protesting the lack of African American managers at the facility.

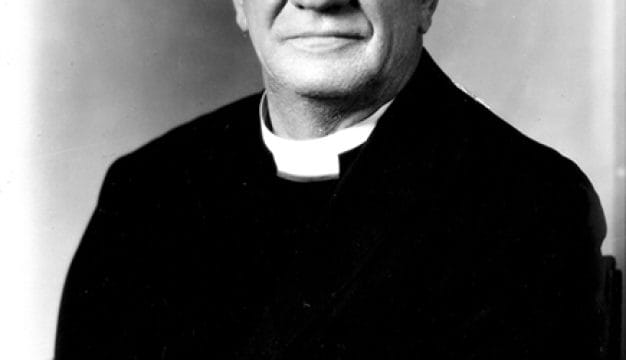

Noble Beasley

In April 1969, NOW was given affiliate status with the SCLC, becoming one of the first new branches of the Atlanta-based organization since King’s death. With the help of SCLC, NOW organized a boycott of the “America’s Junior Miss” pageant a nationally-televised event held in Mobile’s Municipal Auditorium. Leaders of NOW felt that such a public protest in the midst of the pageant would give greater credibility to their grievances. The threat that the demonstrations would become national news prompted city leaders to enact a more stringent ordinance governing public disturbances. During the three-day pageant, more than 300 protesters were arrested outside the municipal auditorium. More than two-thirds of those arrested were under the age of 30, a statistic that mirrored the relative youth of NOW’s membership. NOW’s boycott of the auditorium ultimately proved successful, and the city promoted several African Americans to managerial positions.

Noble Beasley

In April 1969, NOW was given affiliate status with the SCLC, becoming one of the first new branches of the Atlanta-based organization since King’s death. With the help of SCLC, NOW organized a boycott of the “America’s Junior Miss” pageant a nationally-televised event held in Mobile’s Municipal Auditorium. Leaders of NOW felt that such a public protest in the midst of the pageant would give greater credibility to their grievances. The threat that the demonstrations would become national news prompted city leaders to enact a more stringent ordinance governing public disturbances. During the three-day pageant, more than 300 protesters were arrested outside the municipal auditorium. More than two-thirds of those arrested were under the age of 30, a statistic that mirrored the relative youth of NOW’s membership. NOW’s boycott of the auditorium ultimately proved successful, and the city promoted several African Americans to managerial positions.

During the summer of 1969, NOW announced a boycott of the coming municipal election, which threatened to undermine the widespread influence that another local civil rights group, the Non-Partisan Voters’ League, had exerted upon past elections. Since 1953, the League had printed a candidate endorsement pamphlet, called the pink sheet, listing the candidates deemed friendly to the black community. For more than a decade, the pink sheet helped secure the votes of Mobile’s black wards for moderate politicians such as Joseph Langan, who, in turn, worked with leaders such as John LeFlore for modest concessions. LeFlore pleaded with the leaders of the rival organization to reconsider the boycott. But on Election Day, voter turnout in the black wards was particularly low. As a result, Langan lost his seat on the city commission. For the first time since the late 1940s, no winning candidate on the three-person commission carried a black ward.

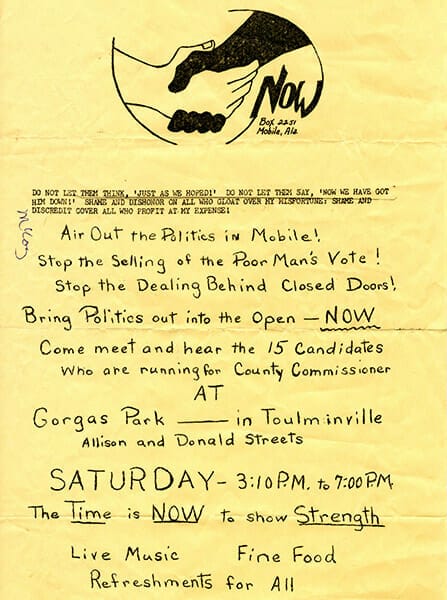

NOW Flier

In many ways, the 1969 election boycott was a costly victory for NOW. Within a year, Noble Beasley and James Finley, a prominent black pharmacist and NOW’s vice president, were indicted on trumped up charges of murder. Although the case was dismissed, other legal battles soon followed, all of which NOW and many members of Mobile’s black community alleged to be politically motivated by white politicians. Finley served 13 months in prison for tax evasion, and Beasley was convicted of drug trafficking and served time until 2005. After Beasley’s conviction in 1973, Frederick D. Richardson, a local postman, became president of the faltering organization, which formally disbanded two years later. Although NOW’s existence was short, it had a direct influence on the city, particularly in elevating the level of public resistance to many long-standing practices of segregation.

NOW Flier

In many ways, the 1969 election boycott was a costly victory for NOW. Within a year, Noble Beasley and James Finley, a prominent black pharmacist and NOW’s vice president, were indicted on trumped up charges of murder. Although the case was dismissed, other legal battles soon followed, all of which NOW and many members of Mobile’s black community alleged to be politically motivated by white politicians. Finley served 13 months in prison for tax evasion, and Beasley was convicted of drug trafficking and served time until 2005. After Beasley’s conviction in 1973, Frederick D. Richardson, a local postman, became president of the faltering organization, which formally disbanded two years later. Although NOW’s existence was short, it had a direct influence on the city, particularly in elevating the level of public resistance to many long-standing practices of segregation.

Further Reading

- Ahmed, Nahfiza. “The Neighborhood Organized Workers of Mobile Alabama: Black Power and Local Civil Rights Activism in the Deep South, 1968-1971.” Southern Historian 20 (1999): 25-40.

- Kirkland, Scotty E. “Pink Sheets and Black Ballots: Politics and Civil Rights in Mobile, Alabama, 1945-1985.” Master’s thesis, University of South Alabama, 2009.

- Neighborhood Organized Workers FBI Files, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

- Richardson, Frederick Douglas. The Genesis and Exodus of NOW. Boynton Beach, Fla.: Futura Press, 1996.