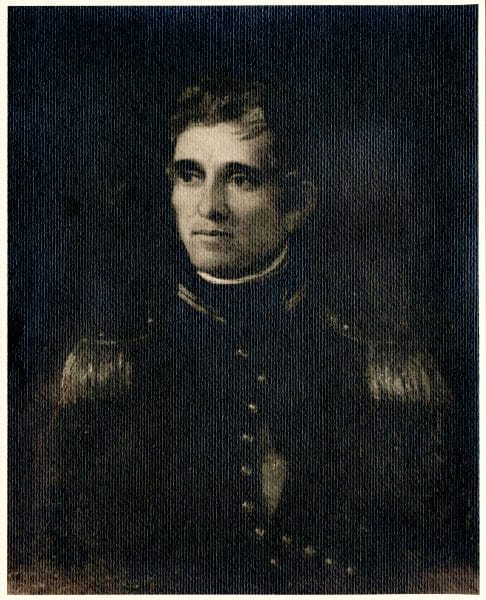

John Floyd

John Floyd (1769-1839) played an important military role in the Mississippi Territory (particularly what is now present-day Alabama) by leading troops in the battles of Autossee and at Calabee Creek during the Creek War of 1813-14. He then returned to his native Georgia, serving the state in many positions, including a term in the U.S. Congress.

John Floyd

Born on October 3, 1769, in Beaufort, South Carolina, John Floyd was the only child of Revolutionary War veteran Capt. Charles Floyd and Mary Fendin Floyd. John reportedly ran away from home at the age of 14 to join the war for American independence as it was nearing its end. After the war, he returned home, became a carpenter’s apprentice for five years, and received a basic education from a private tutor. On December 12, 1793, Floyd married Isabella Maria Hazzard, also from Beaufort, with whom he would have 12 children. In 1795, John Floyd and his new wife moved with his parents to McIntosh County, Georgia. The Floyds moved again in 1800 to Camden County, Georgia, where they established two plantations named Bellevue and Fairfield. In addition to growing cotton and rice, Floyd and his father constructed and sold boats.

John Floyd

Born on October 3, 1769, in Beaufort, South Carolina, John Floyd was the only child of Revolutionary War veteran Capt. Charles Floyd and Mary Fendin Floyd. John reportedly ran away from home at the age of 14 to join the war for American independence as it was nearing its end. After the war, he returned home, became a carpenter’s apprentice for five years, and received a basic education from a private tutor. On December 12, 1793, Floyd married Isabella Maria Hazzard, also from Beaufort, with whom he would have 12 children. In 1795, John Floyd and his new wife moved with his parents to McIntosh County, Georgia. The Floyds moved again in 1800 to Camden County, Georgia, where they established two plantations named Bellevue and Fairfield. In addition to growing cotton and rice, Floyd and his father constructed and sold boats.

Floyd was commissioned captain of the Thirty-first Militia of Camden County on May 2, 1804. He rose steadily through the ranks and within two years was promoted to brigadier general and put in command of the First Brigade, First Division of the Georgia Militia. In 1813, Georgia’s governor gave Floyd command of Georgia militia units that were to participate in coordinated attacks against Red Stick Creek strongholds within present-day central Alabama. In anticipation of the incursion, Floyd set up a base of operations at Camp Hope near Fort Hawkins in central Georgia on the Ocmulgee River in September. From there, he dispatched troops to construct a line of defensive forts and blockhouses westward all the way to the Alabama River. After securing rations to support his soldiers and allied Creeks, on November 24, 1813, Floyd’s forces finally began their march westward and across the Chattahoochee River, where he built Fort Mitchell as a supply base in present-day Russell County.

From Fort Mitchell, Floyd marched his troops approximately 60 miles west to attack the Red Stick town of Autossee on the east bank of the Tallapoosa at the mouth of Calabee Creek. There, Red Stick leaders Peter McQueen and Hopoithle Miko had gathered some 1,500 warriors at various Creek towns in anticipation of an American response to the massacre at Fort Mims. Floyd had hoped to completely surround the town of Autossee to prevent any escape by the Red Sticks there. But a second Creek town was discovered downstream from Autossee, causing Floyd to stretch his troops out more thinly than he had intended. Also, the Tallapoosa River was too cold and deep to cross where Floyd had planned to block escape routes. Finally, a Red Stick hunter had spotted Floyd’s troops and warned the warriors in Autossee of the impending attack.

Floyd nevertheless attacked both towns on November 29, 1813. The Red Sticks put up a fierce resistance but were overwhelmed with superior fire power. As a result, both towns were left in flames and approximately 200 people were killed, and leader Hopoithle Miko, referred to by Floyd as the Tallassee King, was shot; only 11 of Floyd’s men were killed and 53 wounded. Early in the fighting, Floyd’s knee was shattered by a musket ball, but he remained in the field until the end of the battle, refusing to have his wound dressed until all of the wounded had been cared for. Because of a serious shortage of food, Floyd was forced to withdraw his forces to Fort Mitchell instead of pursuing the Red Stick warriors who had escaped and who would later fight in the decisive battle at Horseshoe Bend.

In January 1814, Floyd, having recovered from his wound and replenished his supplies, made another incursion into Creek territory, this time with 1,100 militia and 600 allied Indians. They constructed Fort Hull in present-day Macon County, approximately 40 miles west of Fort Mitchell. Floyd’s Georgia troops then returned to Calabee Creek, where they built the fortified Camp Defiance. In the predawn hours of January 27, 1814, however, Floyd’s army was caught off guard. In the ensuing engagement, often referred to as the Battle of Calabee Creek, Red Stick leader Paddy Walsh led approximately 1,300 warriors who almost seized control of Floyd’s two cannons. Reacting quickly, militia forces secured the cannons, which they then fired at point blank range at the attacking warriors, turning the tide of the battle and saving Floyd’s army from a disastrous defeat. The battle left nearly 50 Red Sticks dead and Paddy Walsh seriously wounded. Approximately 17 of Floyd’s Georgians were killed and 132 wounded.

Floyd then withdrew his army to Georgia because many of its members’ enlistments were soon to expire. He was promoted to major general in recognition of his service and sent to defend Savannah against an anticipated British attack that never materialized. After the War of 1812, Floyd continued to devote much of his life to public service. He helped survey the Georgia-Florida boundary line and later served several years as a justice of the Inferior Court of Camden County. He would also serve as a representative and as a senator from Camden County in the Georgia Legislature from 1820 to 1827. In addition, he was elected to one term in the U.S. Congress in 1827. Floyd was honored by the Georgia Legislature when it created Floyd County on December 3, 1832. He died on June 24, 1839, and is buried in the family cemetery near the site of his plantation home in Camden County.

Further Reading

- Bunn, Mike, and Clay Williams. Battle for the Southern Frontier: The Creek War and the War of 1812. Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2008.

- O’Brien, Sean Michael. In Bitterness and In Tears: Andrew Jackson’s Destruction of the Creeks and Seminoles. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2003.

- Rodgers, Thomas G. “Night Attack at Calabee Creek.” Journal of the Historical Society of the Georgia National Guard 4 (Spring 1995): 12.