Battle of Burnt Corn Creek

Battle of Burnt Corn Creek Artifact

The Battle of Burnt Corn Creek, often cited as the first real battle of the Creek War of 1813-14, took place on July 27, 1813, at a bend in Burnt Corn Creek. The exact location has not been discovered but likely was in present-day Escambia County (then part of Conecuh County) near the line that divides it from Conecuh County. The skirmish occurred during a period of increasing conflict among white settlers and various factions within the Creek Nation that would culminate in the forced removal of most Native Americans from the Southeast. Its more immediate consequence was the massacre of settlers and U.S.-allied Indians at Fort Mims.

Battle of Burnt Corn Creek Artifact

The Battle of Burnt Corn Creek, often cited as the first real battle of the Creek War of 1813-14, took place on July 27, 1813, at a bend in Burnt Corn Creek. The exact location has not been discovered but likely was in present-day Escambia County (then part of Conecuh County) near the line that divides it from Conecuh County. The skirmish occurred during a period of increasing conflict among white settlers and various factions within the Creek Nation that would culminate in the forced removal of most Native Americans from the Southeast. Its more immediate consequence was the massacre of settlers and U.S.-allied Indians at Fort Mims.

In the years before the battle, many Creeks had become increasingly concerned about the rising numbers of white settlers and traders traveling the recently completed Federal Road into the Mississippi Territory, which included present-day Alabama. In response, members of the traditionalist Red Stick faction of Creeks, led by Peter McQueen, travelled to Pensacola, Florida, then under Spanish control, to seek arms from the Spanish governor. On the way, the men burned the plantations of fellow Creeks Sam Moniac and James Cornells and kidnapped Cornells’s wife, who was later ransomed in Pensacola. After much negotiation with the Spanish governor, McQueen acquired about 300 pounds of gunpowder and lead shot.

Old Federal Road

After learning of the attack on the plantations, Mississippi Territory militia leader Col. James Caller, of Washington County, raised a force that eventually numbered about 180 men and set out to intercept the Creeks on the way back from Florida. The militia group included a company raised and commanded by frontiersman Samuel Dale. The force proceeded eastward from Washington County, traveling part of the distance on the Federal Road, crossed the Alabama River on July 26, and reached Burnt Corn Creek on the morning of July 27. Scouts ranging ahead of the force reported that the Red Stick band was enjoying a noon-day meal at a bend in the creek and was unaware of the approaching militia.

Old Federal Road

After learning of the attack on the plantations, Mississippi Territory militia leader Col. James Caller, of Washington County, raised a force that eventually numbered about 180 men and set out to intercept the Creeks on the way back from Florida. The militia group included a company raised and commanded by frontiersman Samuel Dale. The force proceeded eastward from Washington County, traveling part of the distance on the Federal Road, crossed the Alabama River on July 26, and reached Burnt Corn Creek on the morning of July 27. Scouts ranging ahead of the force reported that the Red Stick band was enjoying a noon-day meal at a bend in the creek and was unaware of the approaching militia.

Caller gave the order to attack, and his men surprised the Red Sticks and drove them from their camp into nearby brush. Most accounts of the battle say that Caller’s men, believing the Creeks routed, began to loot the camp and lead the pack horses off. The Red Sticks, however, quickly regrouped and mounted a fierce counterattack on the militia.

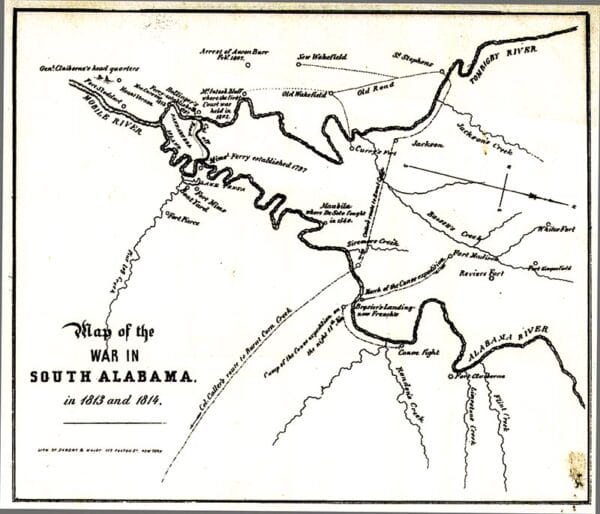

Route Map of Mississippi Militia

Caller’s surprised men turned the order to fall back to a nearby hill into a full-fledged flight. A small band of militia members, led by Samuel Dale, Dixon Bailey, and Benjamin Smoot, stood its ground and thus prevented the disordered retreat from becoming a complete rout. Having left their horses unattended, the militia members fled on foot or mounted the nearest horses, including the pack animals. The Red Sticks pursued the men for a short way but were unable to overtake them. Caller and one of his officers became lost in the swampy woods and were rescued about two weeks later, malnourished and delirious. Total casualties among the militia have been reported as two dead and 10 to 15 wounded; casualties on the Red Stick side were reported as perhaps 10 men. Caller’s militia succeeded in taking much of the shot and powder from the Creeks.

Route Map of Mississippi Militia

Caller’s surprised men turned the order to fall back to a nearby hill into a full-fledged flight. A small band of militia members, led by Samuel Dale, Dixon Bailey, and Benjamin Smoot, stood its ground and thus prevented the disordered retreat from becoming a complete rout. Having left their horses unattended, the militia members fled on foot or mounted the nearest horses, including the pack animals. The Red Sticks pursued the men for a short way but were unable to overtake them. Caller and one of his officers became lost in the swampy woods and were rescued about two weeks later, malnourished and delirious. Total casualties among the militia have been reported as two dead and 10 to 15 wounded; casualties on the Red Stick side were reported as perhaps 10 men. Caller’s militia succeeded in taking much of the shot and powder from the Creeks.

The militia’s embarrassing defeat at Burnt Corn Creek later was satirized in Lewis Sewall‘s poem The Last Campaign of Sir John Falstaff the II; or, The Hero of the Burnt-Corn Battle (1815), written in response to a dispute that Sewall had with Caller, a former friend. In the poem, Caller is compared with Shakespeare’s cowardly and incompetent character Sir John Falstaff and with Cervantes’s delusional Don Quixote. Reportedly, all of the men who took part in the battle immediately mustered out of the militia, and those who were identified as participants were subjected to public ridicule for many years afterward.

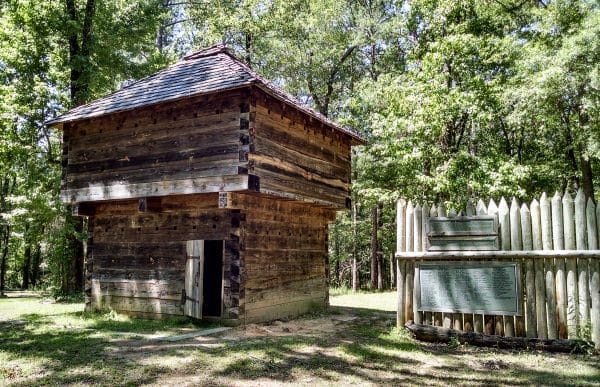

Fort Mims State Historic Site

The more immediate and serious consequence of the attack was the Red Sticks’ retaliatory raid on Fort Mims on August 30, 1813, in which some 700 Red Stick warriors massacred 250 people and took at least 100 captives. Ironically, the settlers and U.S. allied Indians killed or captured at Fort Mims had sought refuge there specifically for protection because of the heightened fear of a Red Stick attack after the battle at Burnt Corn Creek. The Fort Mims attack triggered the outbreak of the Creek War and led to the eventual defeat of the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend and their removal from Alabama.

Fort Mims State Historic Site

The more immediate and serious consequence of the attack was the Red Sticks’ retaliatory raid on Fort Mims on August 30, 1813, in which some 700 Red Stick warriors massacred 250 people and took at least 100 captives. Ironically, the settlers and U.S. allied Indians killed or captured at Fort Mims had sought refuge there specifically for protection because of the heightened fear of a Red Stick attack after the battle at Burnt Corn Creek. The Fort Mims attack triggered the outbreak of the Creek War and led to the eventual defeat of the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend and their removal from Alabama.

Additional Resources

Bunn, Mike, and Clay Williams. Battle for the Southern Frontier: The Creek War and the War of 1812. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press 2008.

Halbert, H. S., and T. H. Ball. The Creek War of 1813 and 1814. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1969.

Waselkov, Gregory A. A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813-14. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.