Gomillion v. Lightfoot

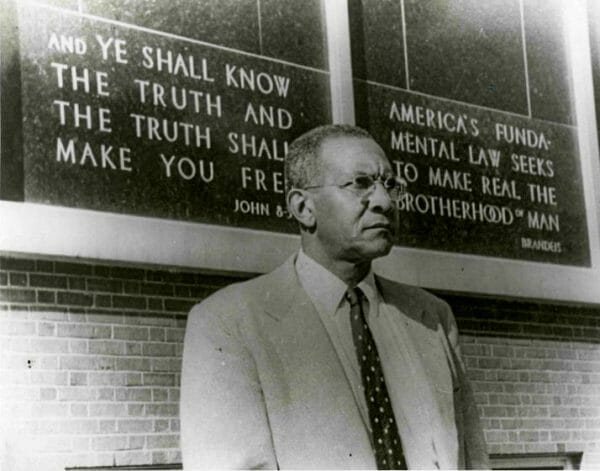

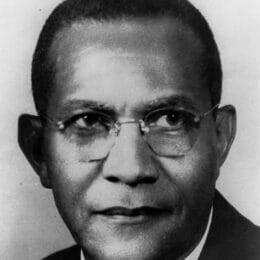

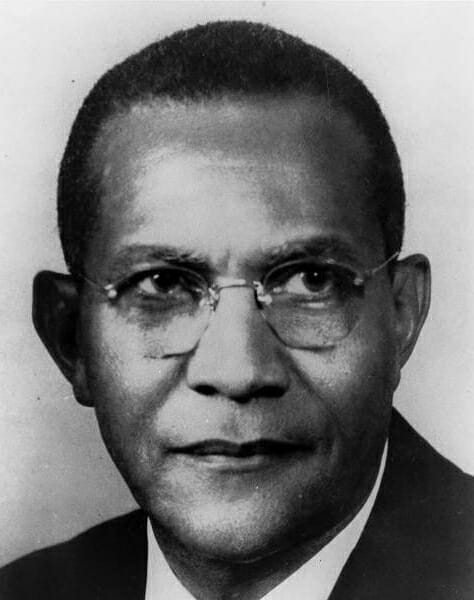

In its 1960 decision in Gomillion v. Lightfoot, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Tuskegee city officials had redrawn the city’s boundaries unconstitutionally to ensure the election of white candidates in the city’s political races. The case was one of several that would lay the foundation for the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices. The case was named for Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (present-day Tuskegee University) professor Charles A. Gomillion, who was lead plaintiff, and the defendant, Tuskegee mayor, Philip M. Lightfoot, among other city officials.

Charles Gomillion

Gomillion, dean of students and chair of the social sciences division at Tuskegee, for years had facilitated voter registration movements for blacks in Tuskegee. He learned in 1957 that several white citizens were promoting a bill in the state legislature to redefine the boundaries of the city to ensure election victories by whites in 1960. Resisting these efforts and urging others to oppose any referenda meant to disfranchise black voters, Gomillion and other activists appealed to the City Council, wrote to the County Commission, lobbied the state legislature, and published an open letter in the Montgomery Advertiser. Despite these efforts, Local Act No. 140, introduced by Samuel M. Engelhardt Jr., passed in the state legislature in 1957. It reconfigured the boundaries of the city from a simple square shape to a figure with 28 sides, removing from the city Tuskegee Institute and all but four or five of the nearly 400 black voters, but none of more than 1,300 white residents. Gomillion and the Tuskegee Civic Association treated this initial setback as an opportunity to institute legal proceedings and thereby to mobilize concerted political action. In addition to legal actions, the city’s citizens also mounted a targeted boycott against white-owned businesses.

Charles Gomillion

Gomillion, dean of students and chair of the social sciences division at Tuskegee, for years had facilitated voter registration movements for blacks in Tuskegee. He learned in 1957 that several white citizens were promoting a bill in the state legislature to redefine the boundaries of the city to ensure election victories by whites in 1960. Resisting these efforts and urging others to oppose any referenda meant to disfranchise black voters, Gomillion and other activists appealed to the City Council, wrote to the County Commission, lobbied the state legislature, and published an open letter in the Montgomery Advertiser. Despite these efforts, Local Act No. 140, introduced by Samuel M. Engelhardt Jr., passed in the state legislature in 1957. It reconfigured the boundaries of the city from a simple square shape to a figure with 28 sides, removing from the city Tuskegee Institute and all but four or five of the nearly 400 black voters, but none of more than 1,300 white residents. Gomillion and the Tuskegee Civic Association treated this initial setback as an opportunity to institute legal proceedings and thereby to mobilize concerted political action. In addition to legal actions, the city’s citizens also mounted a targeted boycott against white-owned businesses.

Gomillion and other petitioners, black citizens of Alabama and residents (or former residents) of Tuskegee, alleged that the act violated the “due process” and “equal protection” clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. They claimed that the redrawn city boundaries disfranchised black voters; therefore, the act had a discriminatory purpose. In fact, the act’s author, Engelhardt, was executive secretary of the White Citizens’ Council of Alabama and an advocate of white supremacy.

Tuskegee’s white citizens were trying to change the city’s boundaries to head off the rise in African Americans registering to vote. After World War II, local African Americans wanted to play a more active role in the city’s civic life, and whites became more determined to deny them that right. Redrawing the city’s boundaries had the unintended effect of uniting Tuskegee Institute’s African American intellectuals with the less educated African Americans living outside the sphere of the school. Some members of the school’s faculty realized that possessing advanced degrees ultimately provided them no different status among the city’s white establishment.

Initially, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama, in Montgomery, headed by Judge Frank M. Johnson, dismissed the case, ruling that the state had the right to draw boundaries, a ruling that was upheld by the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in New Orleans. The case was appealed before the Supreme Court on October 18 and 19, 1960. Gomillion did not travel to Washington, D.C., with the lawyers handling his side of the case. Veteran Alabama civil rights attorney Fred Gray and Robert L. Carter, lead counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), argued the case, with assistance from Arthur D. Shores, who provided additional legal counsel. They claimed that the state’s intent in the redistricting had been to discriminate covertly against African Americans.

On November 14, the Supreme Court rendered a unanimous decision in favor of the petitioners. Justice Felix Frankfurter, writing for the majority, held that the act violated the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibits states from passing laws depriving citizens of the right to vote, and thus reversed the lower courts’ rulings. Frankfurter likewise dismissed the city’s appeal of generalities about state authority. He conceded that states retain extensive powers, but that they may not do whatever they please with municipalities. The case showed that all state powers were subject to limitations imposed by the U.S. Constitution; therefore, states were not insulated from federal judicial review when they jeopardized federally protected rights. In 1961, the results of the decision went into effect; under the direction of Judge Johnson, the gerrymandering was reversed and the original map was reinstituted.

Further Reading

- Elwood, William A. “An Interview with Charles G. Gomillion.” Callaloo 40 (Summer 1989): 576-99.

- Gomillion, C. G. “The Negro Voter in the South.” Journal of Negro Education 26(3): 281-86.

- Norrell, Robert J. Reaping the Whirlwind: The Civil Rights Movement in Tuskegee. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985.

- Taper, Bernard. Gomillion versus Lightfoot: The Tuskegee Gerrymander Case. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1962.