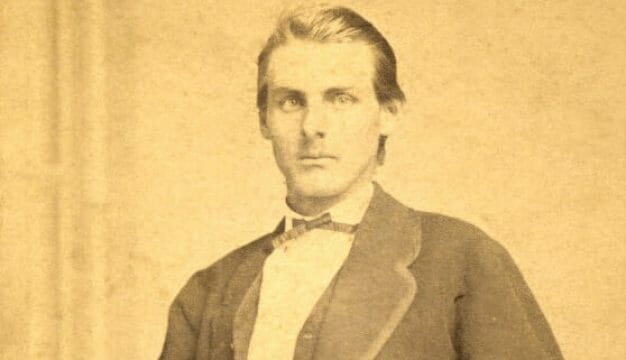

Alva Vanderbilt Belmont

Alva Smith Vanderbilt Belmont (1853-1933) was a champion of woman suffrage and equal rights for women. Belmont provided financial support and leadership for the campaign to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. After its passage, she worked to secure the rights of women beyond U.S. borders.

Alva Erskine Smith was born on January 17, 1853, in Mobile, Mobile County. She was one of five surviving children of Murray Forbes Smith, a cotton merchant, and Phoebe Desha Smith, daughter of U.S. congressman Robert Desha. As sectional tensions increased prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, Smith moved his family to New York City around 1859. Alva attended school in New York, travelled in Europe with her parents, and occasionally summered in Newport, Rhode Island. In 1875, she married William Kissam Vanderbilt, the grandson of railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who was the patriarch of one of the wealthiest families in the United States. She spent her early married life establishing a place for herself and her family in the highest rungs of New York society and building magnificent mansions in New York City, Long Island, New York, and Newport. The couple had three children: Consuelo, William Kissam Jr., and Harold Stirling.

In 1895, Alva Vanderbilt divorced her husband on the grounds of adultery. The divorce decree granted her custody of her children, the right to remarry, and a large financial settlement. Soon after her divorce, she married Oliver H. P. Belmont, the son of August Belmont, who represented the U.S. interests of the Rothschild family, one of the most important banking families in Europe. After Oliver died in 1908 from an infection resulting from an appendectomy, Alva Belmont turned her attention to the cause of women’s rights.

In 1909, Belmont began attending suffrage meetings in New York and joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Observing the activities of the Women’s Social and Political Union, a militant English suffrage organization led by Emmeline Pankhurst, convinced her that a radical approach to suffrage reform was necessary. Returning home from London, she encouraged American suffragists to sponsor parades and mass meetings to publicize women’s demand for the vote. She organized and funded a series of suffrage lectures at her Newport home, Marble House, paid to move the headquarters of the NAWSA to New York City, and established the Political Equality Association, also headquartered in New York City.

She was determined to expand suffrage’s base of support to include working women. So when some 18,000 New York garment workers went on strike in November 1909, she supported their cause by raising money for their strike fund and renting the Hippodrome in midtown Manhattan for a pro-strike rally. She also encouraged the city’s Black women to organize their own suffrage association.

When the leaders of the NAWSA showed little enthusiasm for her tactics and failed to follow the advice she gave them, she left the organization. In 1914, she joined the more radical Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, an organization founded by New Jersey suffragist Alice Paul that eventually became known as the National Woman’s Party (NWP). Its leaders appointed Belmont to their National Council, and she became the organization’s most important benefactor. Between 1914 and her death, she donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to their cause. Her celebrity as a rich society matron meant that the NWP received a great deal of attention from the press. She spent much of her time and money organizing special events and conferences and fundraising. In February 1916, she and a group of fellow volunteers performed her suffrage-themed play, Melinda and Her Sisters, at a fundraiser at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel that netted $8,000 in donations.

In August 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave women the right to vote. Belmont encouraged Alice Paul and the other leaders of the NWP to launch a campaign to eliminate gender discrimination in the United States and abroad and then in 1921 moved to France, where she bought a home on the French Riviera and continued her activism for women’s rights. From there, she helped direct a campaign to assure that women had the same citizenship rights as men. Her interest in the matter emerged when her daughter Consuelo married the Duke of Marlborough, moved to England, and lost her rights as a U.S. citizen. In 1922, the NWP issued its “Declaration of Principles,” which outlined its commitment to guaranteeing women equal access to education and employment. It demanded equal pay for equal work and equality before the law. And it declared that a woman had a right to control over her own body, a right to control her property, a right to divorce, and a right to custody of her children. In 1929, the NWP purchased a home in Washington, D.C., to serve as its headquarters, naming it the Alva Belmont House (it is now the Sewall-Belmont House National Historic Site).

In pursuit of equal citizenship rights, Alva financed a campaign directed by Alice Paul and Doris Stevens, who worked through international organizations such as the Pan-American Union, to assure the passage of an equal nationality rights treaty. In 1926, Belmont, Paul, and others established the International Advisory Council of the NWP to monitor the legal position of women abroad.

In 1932, Belmont suffered a debilitating stroke and died the following year on January 26, leaving $100,000 to the NWP in her will. Her body was returned to New York, where she was buried next to Oliver Belmont in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. As part of her legacy, the delegates of the Pan-American Conference in Montevideo, Uruguay, signed an equal nationality treaty in late 1933, and on May, 24, 1934, Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Equal Nationality Act, which confirmed the principle that marriage had no impact whatsoever on the citizenship of Americans. On the same day, the U. S. Senate ratified the Montevideo Treaty.

Further Reading

- Ford, Linda G. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party, 1912-1919. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1991.

- Keeler, Rebecca T. “Alva Belmont: Exacting Benefactor for Women’s Suffrage.” Alabama Review 41 (April 1988): 132-45.

- Hoffert, Sylvia D. Alva Vanderbilt Belmont: Unlikely Champion of Women’s Rights. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011.

- Sledge, John. “Alva Smith Vanderbilt Belmont: Alabama’s ‘Bengal Tiger.’” Alabama Heritage 44 (Spring 1997): 6-17.

- Stuart, Amanda Mackenzie. Consuelo and Alva Vanderbilt: The Story of a Daughter and a Mother in the Gilded Age. New York: HarperCollins, 2005.