Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights

The Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) was the most important civil rights organization in Birmingham during the black freedom struggle of the 1950s and 1960s. It was formed in 1956 by minister Fred Lee Shuttlesworth after the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was prohibited from operating in Alabama. The organization engaged in bus boycotts, sit-ins, and other forms of protest and is especially noted for organizing the Birmingham Campaign of 1963. The group was also known for its greater willingness to confront local authorities than civil rights groups in Montgomery. A key strategy was to protest a segregation ordinance and challenge the ordinance in court.

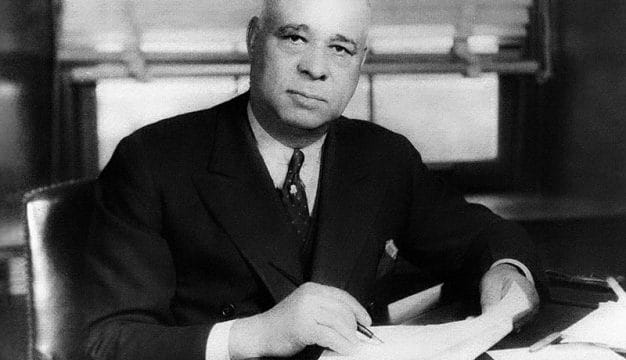

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

In 1956, Alabama Attorney General John M. Patterson sued the NAACP, claiming the organization was not eligible to do business in the state. A circuit court agreed and issued an injunction against all NAACP activities within Alabama on June 1, 1956. Responding to what he understood as a divine mandate, Shuttlesworth, who was pastor of the Bethel Baptist Church and an NAACP member, met that day with other black ministers, including Robert Alford, Edward Gardner, T. L. Lane, George Pruitt Sr., Herman Stone, and Nelson Smith Jr. The group agreed to form a new organization as a replacement for the NAACP. The following day, the group drew up a declaration of resolutions and formed committees in anticipation of a June 5 mass meeting.

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

In 1956, Alabama Attorney General John M. Patterson sued the NAACP, claiming the organization was not eligible to do business in the state. A circuit court agreed and issued an injunction against all NAACP activities within Alabama on June 1, 1956. Responding to what he understood as a divine mandate, Shuttlesworth, who was pastor of the Bethel Baptist Church and an NAACP member, met that day with other black ministers, including Robert Alford, Edward Gardner, T. L. Lane, George Pruitt Sr., Herman Stone, and Nelson Smith Jr. The group agreed to form a new organization as a replacement for the NAACP. The following day, the group drew up a declaration of resolutions and formed committees in anticipation of a June 5 mass meeting.

ACMHR chose its name very deliberately. Shuttlesworth reasoned that city officials could outlaw an organization but could not outlaw a movement. Including “Christian” in the title would distinguish it from Communist and other supposedly subversive groups while giving it a foundation and Christian orientation. Shuttlesworth also emphasized human rights as being more inclusive than civil rights, and Alford, of the Sardis Baptist Church where the group met, suggested that “Alabama” be included as he expected the movement to extend beyond Birmingham. At the June 5 mass meeting, attended by as many as 1,000 individuals at Alford’s church, Shuttlesworth was elected president and Edward Gardner vice president. ACMHR was incorporated in August.

Each Monday night thereafter, Shuttlesworth led mass meetings to provide information and inspiration for other interested parties. Several hundred individuals routinely attended these gatherings at various churches in the city and donated funds. Roughly 1,000 individuals, 60 percent of which were women, belonged to the organization in 1959 according to a survey. In contrast to the NAACP, ACMHR membership largely consisted of working-class individuals and received little support from upper- and middle-class blacks, whose church leaders thought the group too militant. Within a year of its inception, plainclothes Birmingham police detectives employed by public safety commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor began infiltrating and secretly taping meetings. They then transcribed the recordings and provided Connor with written documentation of ACMHR activities. These written records would later prove invaluable to historians of the civil rights movement.

Eugene “Bull” Connor

Overall, the ACMHR reflected Shuttlesworth’s peculiar charisma, characterized by relentless and sometimes reckless assaults on segregation “on all fronts.” ACMHR confrontations with the city’s police and fire departments extended the often theatrical public battles between Shuttlesworth and Connor, and the men became symbols of the forces pulling the South apart in the era of “massive resistance.” Connor’s harsh methods did not dissuade ACMHR members from following Shuttlesworth. Uniformed police issued parking tickets and detectives took notes, yet ACMHR members continued to attend mass meetings. When meetings were interrupted by false fire reports, ACMHR followers marched to other churches to continue their meetings. These actions were viewed as confrontational by local whites and Connor’s forces and even many of Birmingham’s middle-class blacks, who referred to Shuttlesworth’s supporters as “Shuttle-ites.”

Eugene “Bull” Connor

Overall, the ACMHR reflected Shuttlesworth’s peculiar charisma, characterized by relentless and sometimes reckless assaults on segregation “on all fronts.” ACMHR confrontations with the city’s police and fire departments extended the often theatrical public battles between Shuttlesworth and Connor, and the men became symbols of the forces pulling the South apart in the era of “massive resistance.” Connor’s harsh methods did not dissuade ACMHR members from following Shuttlesworth. Uniformed police issued parking tickets and detectives took notes, yet ACMHR members continued to attend mass meetings. When meetings were interrupted by false fire reports, ACMHR followers marched to other churches to continue their meetings. These actions were viewed as confrontational by local whites and Connor’s forces and even many of Birmingham’s middle-class blacks, who referred to Shuttlesworth’s supporters as “Shuttle-ites.”

After its inception, the organization’s first task was to renew Shuttlesworth’s call for the integration of the Birmingham Police Department. After several months of pressure and the threat of a lawsuit filed by two applicants, the city quietly changed its “whites only” policy and eventually opened other city jobs to blacks. Hoping to model the successful Montgomery bus boycott, Shuttlesworth led a similar ACMHR effort to integrate the buses in Birmingham. When the transit company refused to alter its segregated seating policy and city officials provided no assistance, ACMHR members prepared to ignore seating restrictions on December 26, 1956. On Christmas night, segregationists dynamited Shuttlesworth’s parsonage, hoping to kill or at least scare him out of town, but he emerged from the blast unharmed, emboldening him and ACMHR. The next day as planned, Shuttlesworth, other ACMHR members, and individual black riders sat in the front seats on Birmingham buses. For their efforts, 21 individuals were arrested, but as many as 200 blacks had ridden in white sections without incident. Shuttlesworth was also arrested that day for driving without a license and improper vehicle documentation. ACMHR members were encouraged to continue the protest by Martin Luther King Jr., and the Montgomery Improvement Association, but Shuttlesworth urged the organization to await the outcome of test cases.

In October 1958, AMHCR again challenged the segregated seating policy, resulting in the arrest of 13 riders as well as Shuttlesworth for his role in arranging the protest. These actions and the arrest of three ministers visiting from Montgomery won over the more conservative Jefferson County Betterment Association, which joined with the ACMHR to organize a bus boycott. The city responded by intimidating participants, and many blacks refused to participate. The press largely ignored the effort. The Birmingham Bus Boycott was over by the end of the year. Also in October 1958, the organization petitioned the city to desegregate parks and recreation facilities. The city closed recreational facilities in 1962, however, rather than comply with federal court orders to integrate.

In 1960, the ACMHR supported and provided training in nonviolence techniques for sit-ins by students at Miles College in Fairfield. Also that year, Shuttlesworth and the ACMHR filed an unsuccessful suit against the city in an attempt to force the police department to give up its regular surveillance of the organization’s meetings. The following year, ACMHR members acted as contacts and general caretakers for groups of students who began arriving in the city during the May Freedom Rides. In June, Shuttlesworth accepted the pastorate of a Baptist church in Cincinnnati, Ohio, but traveled biweekly from Cincinnati to Birmingham in an effort to sustain the civil rights movement

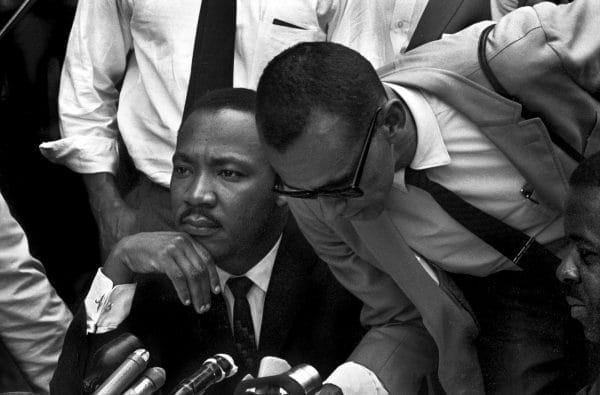

Martin Luther King and Wyatt Tee Walker

Shuttlesworth often pressed King to bring the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which Shuttlesworth helped found, to Birmingham for joint protests with the ACMHR. King eventually committed himself to major protests in 1963 that became known as the Birmingham Campaign. ACMHR members helped SCLC executive director Wyatt Tee Walker organize the demonstrations, originally known as Project C, for “confrontation.” In April, the group initiated a combination of sit-ins and boycotts of local business that aimed to force the business community to push city leaders into passing desegregation ordinances. National and international news agencies depicted marches that included the more than 2,000 youthful protesters of the Children’s Crusade, many of whom were arrested and completely clogged the jails of Birmingham. Federal officials sent by Pres. John F. Kennedy mediated between ACMHR and SCLC and the city’s leaders to end the protests and implement reforms. On May 10, Birmingham merchants in turn reluctantly agreed to begin desegregating their downtown department stores. Significantly, the demonstrations and the city’s aggressive response helped convince Kennedy to introduce into Congress legislation that eventually became the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Martin Luther King and Wyatt Tee Walker

Shuttlesworth often pressed King to bring the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which Shuttlesworth helped found, to Birmingham for joint protests with the ACMHR. King eventually committed himself to major protests in 1963 that became known as the Birmingham Campaign. ACMHR members helped SCLC executive director Wyatt Tee Walker organize the demonstrations, originally known as Project C, for “confrontation.” In April, the group initiated a combination of sit-ins and boycotts of local business that aimed to force the business community to push city leaders into passing desegregation ordinances. National and international news agencies depicted marches that included the more than 2,000 youthful protesters of the Children’s Crusade, many of whom were arrested and completely clogged the jails of Birmingham. Federal officials sent by Pres. John F. Kennedy mediated between ACMHR and SCLC and the city’s leaders to end the protests and implement reforms. On May 10, Birmingham merchants in turn reluctantly agreed to begin desegregating their downtown department stores. Significantly, the demonstrations and the city’s aggressive response helped convince Kennedy to introduce into Congress legislation that eventually became the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Shuttlesworth continued to travel frequently from Cincinnati to Birmingham, but his frequent absences weakened the organization, and he resigned as president in 1969. Members elected Ed Gardner as president. Attempts to maintain the organization were further weakened when the SCLC launched a Birmingham branch in the early 1970s. The organization did continue to advocate for civil rights in this period, notably helping to organize protest rallies after the arrest of leaders of the Alabama Black Liberation Front in Tarrant in 1970. Before its eventual dissolution, however, the members of ACMHR had provided the indispensable personal support and institutional strength for some of the most dramatic events of the national civil rights movement.

Further Reading

- Eskew, Glenn T. But for Birmingham: The Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Garrow, David J. Birmingham, Alabama, 1956-1963: The Struggle for Black Rights. Brooklyn: Carlson Publishing, 1989.

- Manis, Andrew M. A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

- White, Marjorie, and Andrew M. Manis, eds. Birmingham Revolutionaries: Fred Shuttlesworth and the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 2000.