William Weatherford

William Weatherford (ca. 1781-1824), arguably the best known Red Stick war leader in the Creek War of 1813-14, was born around 1781 near the town of Coosada, an Alabama town of the Creek confederacy. Weatherford was born into the Wind clan, and through his extended matrilineal kin network was closely related to some of the most powerful and high-ranking Creeks of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, including Alexander McGillivray, whose mother was Weatherford’s grandmother. Raised as a high status Creek man in a bicultural family, Weatherford was exposed both to trade and the emerging plantation economy, which many of his family members, including half-brother David Tate, embraced. As a young man, Weatherford took on the leadership role expected from a young man of his lineage and status and distinguished himself in the usual pursuits of Creek men, including ball play, horsemanship, hunting, and training for warfare.

His first documented public role came in 1801, when, with a group of young warriors, he helped seize William Augustus Bowles, a former Loyalist whose activities were condemned by the Spanish, American, and Creek leadership. As a young man in the years leading up to the Creek War, he continued to trade in both deerskins and cattle.

In 1813, as civil war divided the Creek people, Weatherford assumed an active leadership role in Red Stick military efforts. Weatherford’s decision to join the Red Sticks is not well understood. Many of his relatives took the opposite side, and after the war, his relatives would claim that he only joined to control the violence of the movement. But available evidence indicates his dedication to the Red Stick cause. Notably, he led the attack against the garrison established at the home of Samuel Mims, referred to as Fort Mims. There, on August 30, Red Stick leaders Weatherford, the Far-off Warrior, and Paddy Walsh, and nearly 700 Creek warriors carried out a successful assault against the fort. The Mississippi Territorial Volunteers stationed there were taken by surprise, and Red Stick Creeks quickly entered the fort around noon. Over the next four hours, the Red Sticks killed most of its defenders and civilian inhabitants, an estimated 250 people, and took at least 100 captives. The destruction of Fort Mims was the first significant action of the Creek War and transformed the conflict from an Indian civil war into an American-Creek war as news of the massacre of women and children whipped up retaliatory fervor among the American citizenry.

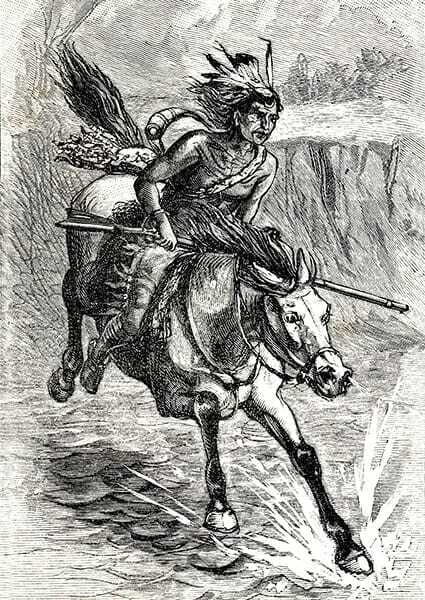

Weatherford’s Leap

After the victory at Fort Mims, Weatherford continued to participate in the Red Stick war effort along the Alabama and Tallapoosa rivers. He and other Red Sticks established a fortified village at Econochaca, or “Holy Ground.” There, in late December 1813, Weatherford supervised the defense of the town against an assault by Gen. Ferdinand Claiborne, who led the Third U. S. Infantry, Mississippi militia, and Choctaw volunteers into the heart of the Creek Nation in retaliation for Fort Mims. As the American forces approached, warriors evacuated women and children and, then, along with freed African American slaves, defended the town before retreating and escaping. Weatherford escaped by leaping on horseback from a bluff into the Alabama River amid a hail of gunfire.

Weatherford’s Leap

After the victory at Fort Mims, Weatherford continued to participate in the Red Stick war effort along the Alabama and Tallapoosa rivers. He and other Red Sticks established a fortified village at Econochaca, or “Holy Ground.” There, in late December 1813, Weatherford supervised the defense of the town against an assault by Gen. Ferdinand Claiborne, who led the Third U. S. Infantry, Mississippi militia, and Choctaw volunteers into the heart of the Creek Nation in retaliation for Fort Mims. As the American forces approached, warriors evacuated women and children and, then, along with freed African American slaves, defended the town before retreating and escaping. Weatherford escaped by leaping on horseback from a bluff into the Alabama River amid a hail of gunfire.

Weatherford and the Red Stick war leaders then regrouped to face Gen. John Floyd and his force of nearly 1,500 men, including Georgia militia and allied Creek Indians, whose aims were Creek towns along the Tallapoosa River, particularly the Red Stick stronghold at Autossee. After burning Autossee, Floyd’s force established a fortified position near Calabee Creek. Weatherford, along with other Red Stick leaders, rallied an estimated 1,300 warriors but apparent differences in tactics led Weatherford to withdraw from the planned attack, which surprised the Georgians and caused considerable damage, killing 22 and wounding 150 of the allied force. Floyd’s troops were then forced to withdraw.

The action at Calebee Creek seemingly ended Weatherford’s participation in the war until his famous surrender to Gen. Andrew Jackson, who established headquarters at Camp Jackson on the site of the old French Fort Toulouse, after his rout of Upper Creeks at Horseshoe Bend. After his surrender, Weatherford cooperated with Jackson’s forces and persuaded other Red Stick insurgents to surrender. He also participated in military actions against those who would not.

As the vilified leader of the horrific action at Fort Mims, Weatherford might logically have expected to have been executed for his role in the war. Instead, his prominent family, many of whom fought against the Red Sticks, waged a rehabilitation campaign on his behalf, celebrating his bravery and horsemanship, turning his famous leap from the cliff at Holy Ground and his peaceful surrender to Andrew Jackson into legendary feats of heroic virtue. In letters and other forums, family members also stressed his supposed coerced or reluctant participation in the

Grave of William Weatherford

conflict and claimed he left Fort Mims before the murder of women and children, thereby hoping to distance the heroic warrior from the deeds of war. Moreover, his open cooperation with Jackson’s army at the end of the war, coupled with the protection of his family, assuaged notions of Weatherford as the “savage” warrior and promoted him as the noble leader who tried to serve his misguided people bravely and attempted to restrain their excesses. After the war, under the protection of his prominent kin, he lived as a plantation owner in south Alabama, distancing himself from tribal affairs. When he died in 1824, he was married to a Christian woman of mixed Indian ancestry and left sizeable property in land and slaves to his descendants.

Grave of William Weatherford

conflict and claimed he left Fort Mims before the murder of women and children, thereby hoping to distance the heroic warrior from the deeds of war. Moreover, his open cooperation with Jackson’s army at the end of the war, coupled with the protection of his family, assuaged notions of Weatherford as the “savage” warrior and promoted him as the noble leader who tried to serve his misguided people bravely and attempted to restrain their excesses. After the war, under the protection of his prominent kin, he lived as a plantation owner in south Alabama, distancing himself from tribal affairs. When he died in 1824, he was married to a Christian woman of mixed Indian ancestry and left sizeable property in land and slaves to his descendants.

Weatherford is nearly universally called Red Eagle by writers. The sobriquet has no basis in fact. According to a family friend, Thomas Woodward, Weatherford was known by two Creek names, Hoponika Fulsahi (Truth Maker) and Billy Larney, which translates as Yellow Billy. The name “Red Eagle” did not appear in print until the 1855 publication of A. B. Meek’s poem “The Red Eagle: A Poem of the South,” a lengthy romanticized tale based loosely on Weatherford and his exploits.

Additional Resources

Halbert, Henry S., and Timothy H. Ball. The Creek War of 1813 and 1814. 1895. Reprint edited by Frank L. Owsley Jr. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

Owsley, Frank L., Jr. Struggle for the Gulf Borderlands: The Creek War and the Battle of New Orleans, 1812-1815. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1981.

Waselkov, Gregory A. A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813-14. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.