Battle of Decatur

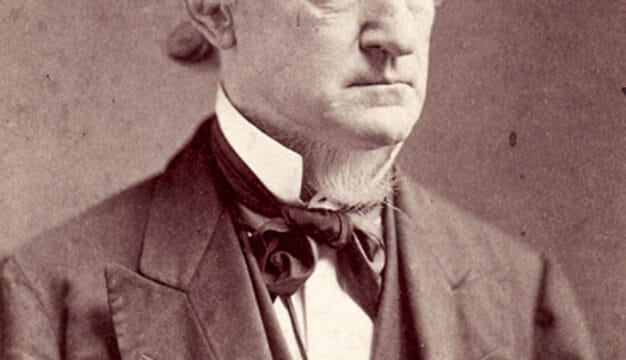

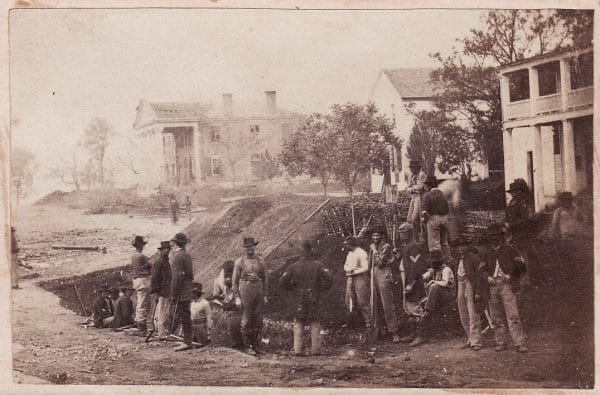

Federal Soldiers in Downtown Decatur

The Battle of Decatur, fought from October 26 to October 29, 1864, was the result of Confederate general John Bell Hood’s effort to move his army across the Tennessee River and into central Tennessee to reclaim Nashville, Tennessee. The battle occurred as part of the larger Franklin-Nashville Campaign. The federal garrison at Decatur, in Limestone and Morgan counties, commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert S. Granger, prevented Hood from crossing and forced him to move his army westward and eventually ford the river at Tuscumbia, Colbert County. Ultimately the engagement at Decatur would delay Hood’s crossing of the Tennessee River by four days and contribute to his failure to retake Nashville for the Confederacy.

Federal Soldiers in Downtown Decatur

The Battle of Decatur, fought from October 26 to October 29, 1864, was the result of Confederate general John Bell Hood’s effort to move his army across the Tennessee River and into central Tennessee to reclaim Nashville, Tennessee. The battle occurred as part of the larger Franklin-Nashville Campaign. The federal garrison at Decatur, in Limestone and Morgan counties, commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert S. Granger, prevented Hood from crossing and forced him to move his army westward and eventually ford the river at Tuscumbia, Colbert County. Ultimately the engagement at Decatur would delay Hood’s crossing of the Tennessee River by four days and contribute to his failure to retake Nashville for the Confederacy.

Following the fall of Atlanta, Georgia, in September 1864, Gen. Hood and his Army of Tennessee retreated south, hoping the U.S. military forces in Atlanta, commanded by Gen. William T. Sherman, would follow. Unfortunately for Hood, Sherman did not take the bait, prompting Hood to alter his plan and head north to attack Sherman’s railroad supply lines between Atlanta and Chattanooga, Tennessee. Wanting to protect his vital rail and telegraph lines, Sherman initially turned north to confront Hood. Hood, hoping to maneuver Sherman out of Georgia, consequently moved his army west towards Gadsden in Etowah County. At this point, Sherman decided against following Hood and instead returned to Atlanta, where he soon launched his “March to the Sea.” The Confederate commander, now aware that Sherman was not pursuing him, developed his plan to retake Nashville, which had fallen to the U.S. Army in 1862. This would require him to move his army across the Tennessee River and into central Tennessee.

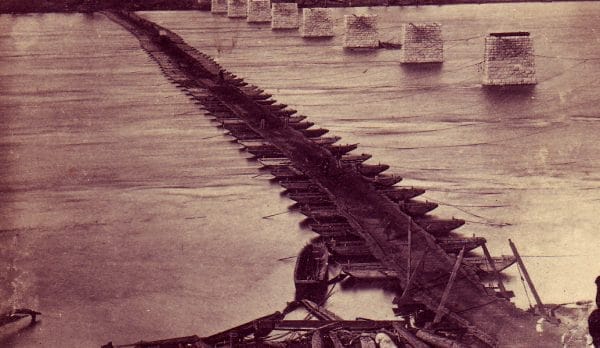

U.S. Army Pontoon Bridge, 1864

Hood originally intended to cross the river at Guntersville, Marshall County; however, reports of a strong defensive force and gunboats patrolling that area of the river convinced him to search for an easier crossing further west. Given the presence of a pontoon bridge constructed by federal troops and its location on a strategic railroad juncture, Decatur seemed an opportune location to ford the river. On October 26, in the midst of a heavy rain, Hood ordered his army to surround the town. The U.S. commander of the District of Northern Alabama, Gen. Robert S. Granger, rushed from Huntsville to Decatur to take personal command of the garrison stationed there. Granger was an experienced commander who had distinguished himself at the battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga before being promoted to district commander. Seeing that his force of 3,000 men faced the entirety of Hood’s 23,000-man army, Granger requested reinforcements from Gen. George Thomas in Nashville. Skeptical that Granger truly faced all of Hood’s forces, Thomas sent only two regiments to reinforce Decatur and ordered Granger to “hold his post at all costs.”

U.S. Army Pontoon Bridge, 1864

Hood originally intended to cross the river at Guntersville, Marshall County; however, reports of a strong defensive force and gunboats patrolling that area of the river convinced him to search for an easier crossing further west. Given the presence of a pontoon bridge constructed by federal troops and its location on a strategic railroad juncture, Decatur seemed an opportune location to ford the river. On October 26, in the midst of a heavy rain, Hood ordered his army to surround the town. The U.S. commander of the District of Northern Alabama, Gen. Robert S. Granger, rushed from Huntsville to Decatur to take personal command of the garrison stationed there. Granger was an experienced commander who had distinguished himself at the battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga before being promoted to district commander. Seeing that his force of 3,000 men faced the entirety of Hood’s 23,000-man army, Granger requested reinforcements from Gen. George Thomas in Nashville. Skeptical that Granger truly faced all of Hood’s forces, Thomas sent only two regiments to reinforce Decatur and ordered Granger to “hold his post at all costs.”

On the morning of October 27, Hood ordered his men to dig in and construct artillery emplacements. The Confederates thus faced an impressive array of fortifications consisting of earthworks, trenches, abatises (obstacles made of brush and sharpened logs), and artillery emplacements. Undaunted, Hood ordered skirmishers forward, and sporadic fighting broke out late in the day. Granger sent out a force of his own skirmishers the following day that repulsed some of the southern forces. Despite a thick fog that impeded both sides, Granger, hoping to capitalize on his earlier success, sent out a larger detachment later that day and beat back Hood’s advance forces.

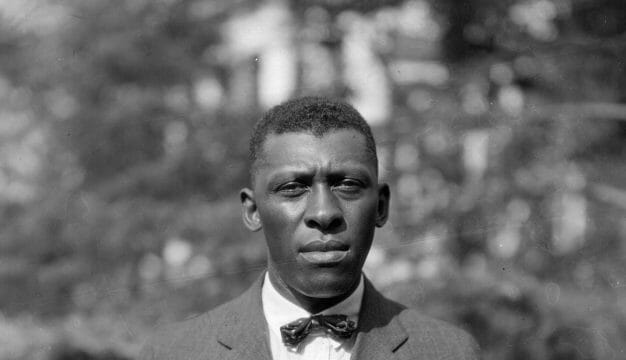

Charles Tyree

The federal counter-offensive included one of the regiments Thomas had sent from Chattanooga: the 14th United States Colored Troops (USCT). This regiment of ex-slaves, led by Col. Thomas J. Morgan, had seen its first combat just two months earlier at Dalton, Georgia. Despite their relative inexperience, the men of the 14th USCT distinguished themselves by driving back Confederate artillerymen and disabling two pieces of artillery before retreating back to the safety of the federal lines. The African American troops, who in addition to facing the scorn of Confederates they encountered, often faced racial prejudice within their own army, were greeted with cheers from Decatur’s white defenders. Referring to their behavior in battle, Col. Morgan assured his men that their exemplary behavior in battle would silence their critics and elicit praise from their comrades.

Charles Tyree

The federal counter-offensive included one of the regiments Thomas had sent from Chattanooga: the 14th United States Colored Troops (USCT). This regiment of ex-slaves, led by Col. Thomas J. Morgan, had seen its first combat just two months earlier at Dalton, Georgia. Despite their relative inexperience, the men of the 14th USCT distinguished themselves by driving back Confederate artillerymen and disabling two pieces of artillery before retreating back to the safety of the federal lines. The African American troops, who in addition to facing the scorn of Confederates they encountered, often faced racial prejudice within their own army, were greeted with cheers from Decatur’s white defenders. Referring to their behavior in battle, Col. Morgan assured his men that their exemplary behavior in battle would silence their critics and elicit praise from their comrades.

The breakdown of Hood’s supply network further compounded the difficulties of his movements in northern Alabama. Hood, who insisted upon rapid movement, largely kept his superior, Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard, in the dark as to his army’s movements. Thus, Beauregard could not coordinate with the quartermaster’s office to supply the Army of Tennessee, greatly hampering Hood’s troops, many of whom were without shoes and rations.

The lack of provisions and the stiff resistance put forth by Granger’s garrison, combined with the arrival of two U.S. Navy gunboats, convinced Hood and Beauregard, who had arrived on the scene the night of October 27, that further action against Decatur would be foolhardy. In the three-day engagement, the South suffered 450 casualties, whereas the U.S. Army lost 155 men. On October 29, Hood ordered his army to withdraw from Decatur and continue westward to Courtland and eventually to Tuscumbia, where the shallow waters of Muscle Shoals prevented federal gunboats from approaching too closely. Here, 80 miles away from its intended crossing point, Hood’s army finally forded the Tennessee River on October 30 and arrived at Florence, Lauderdale County. From there, Hood would lead the Army of Tennessee to defeat at Franklin, Tennessee, and to its ultimate ruin at the Battle of Nashville.

Additional Resources

McMurry, Richard M. John Bell Hood and the War for Southern Independence. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

Sword, Wiley. The Confederacy’s Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992.

Trudeau, Noah Andre. Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War, 1862-1865. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1998.