Iron and Steel Museum of Alabama

Iron & Steel Museum of Alabama

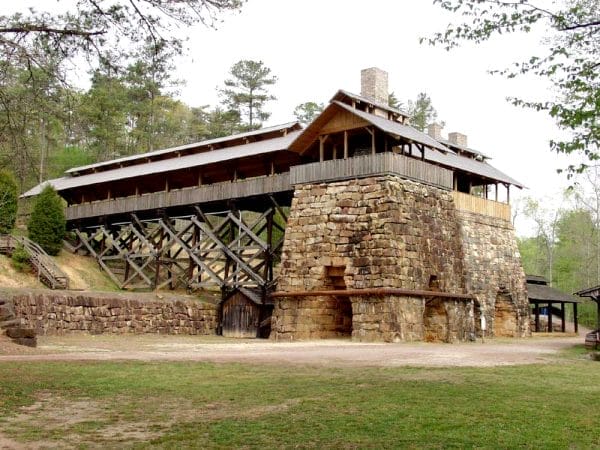

The Iron and Steel Museum of Alabama, located at Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park is a regional interpretive center focusing on iron making in the nineteenth century. Built in 1981, 12 miles south of Bessemer, the museum houses an extensive collection of machines and artifacts relating to the iron industry from the Civil War era through the 1960s. It is also the site of the Walter B. Jones Center for Industrial Archaeology and is within walking distance of the Tannehill Ironworks, which was a major producer of Confederate iron before it was burned during Wilson’s Raid on March 31, 1865. The furnaces, among the best preserved in the South, are linked to the museum by the Tram Track Hiking Trail. Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park is part of the national Civil War Discovery Trail and attracts some 400,000 tourists annually.

Iron & Steel Museum of Alabama

The Iron and Steel Museum of Alabama, located at Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park is a regional interpretive center focusing on iron making in the nineteenth century. Built in 1981, 12 miles south of Bessemer, the museum houses an extensive collection of machines and artifacts relating to the iron industry from the Civil War era through the 1960s. It is also the site of the Walter B. Jones Center for Industrial Archaeology and is within walking distance of the Tannehill Ironworks, which was a major producer of Confederate iron before it was burned during Wilson’s Raid on March 31, 1865. The furnaces, among the best preserved in the South, are linked to the museum by the Tram Track Hiking Trail. Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park is part of the national Civil War Discovery Trail and attracts some 400,000 tourists annually.

The museum grew out of efforts to document and preserve the Tannehill site, which was the birthplace of the Birmingham iron industry beginning with the establishment of Hillman’s Forge in 1830. It was first proposed as a state park in the late 1960s by representatives of the University of Alabama and the Alabama Central District of Civitan International, including local Civitan clubs in Woodstock and Tuscaloosa. Legislation creating the Tannehill project was passed by the Alabama State Legislature in 1969 and the park opened in 1970.

The site today is an American Society for Metals international landmark and home to the Alabama Forge Council. The museum staff, including an industrial archaeologist, provides tours and educational programming for thousands of school children through the Tannehill Learning Center, a cooperative effort with the University of Alabama College of Education.

Historic Furnaces at Tannehill

The main museum building includes more than 13,000 square feet of exhibit space, a reconstructed machine shop from the 1870s, and four period steam engines, including an 1835 Dotterer engine that once belonged to the collection of auto pioneer Henry Ford. Exhibits include a large collection of Confederate artillery projectiles manufactured at the Selma Naval Gun Foundry, relics recovered from the CSS Alabama, rifles and other weapons used by Union and Confederate soldiers, and a large distillation kettle used at the Confederate saltpeter works at Sauta Cave near Scottsboro. Other displays include a model of an 1860s bloomery forge and helve hammer, a precursor of the Tannehill blast furnace, Alabama minerals, furnace products and industrial relics, period cast-iron water pipes, an 1864 cannon lathe, a spike-making machine from the Tredegar Ironworks in Virginia, and a collection of rare cast-iron cookware.

Historic Furnaces at Tannehill

The main museum building includes more than 13,000 square feet of exhibit space, a reconstructed machine shop from the 1870s, and four period steam engines, including an 1835 Dotterer engine that once belonged to the collection of auto pioneer Henry Ford. Exhibits include a large collection of Confederate artillery projectiles manufactured at the Selma Naval Gun Foundry, relics recovered from the CSS Alabama, rifles and other weapons used by Union and Confederate soldiers, and a large distillation kettle used at the Confederate saltpeter works at Sauta Cave near Scottsboro. Other displays include a model of an 1860s bloomery forge and helve hammer, a precursor of the Tannehill blast furnace, Alabama minerals, furnace products and industrial relics, period cast-iron water pipes, an 1864 cannon lathe, a spike-making machine from the Tredegar Ironworks in Virginia, and a collection of rare cast-iron cookware.

In addition to its iron-industry content, the main museum building houses more than 10,000 artifacts uncovered on the site from eight major archaeological investigations from 1956 to 2008, as well as a small research library containing hundreds of books, pictures, and documents. The museum has become a major repository for archives, records, publications, and first-hand accounts for scholars and students studying the history of the iron industry in the South. Finally, the facility also includes a 30-seat theatre that features a short video on the park’s history and activities. It is frequently used for seminars and meetings. The museum underwent a major make-over in 2005 with funding from the Save America’s Treasure’s program through the U.S. Department of Interior. Other museum buildings include the 1858 May Plantation Cotton Gin House and an exhibit center containing artifacts from Birmingham’s steel industry dating from the 1930s to the 1960s.

Further Reading

- Alabama Ironworks Source Book. McCalla, Ala.: Alabama Historic Ironworks Commission, 2006.

- Bennett, James R. Tannehill and the Growth of the Alabama Iron Industry. McCalla, Ala.: Alabama Historic Ironworks Commission, 1999.

- ———. Old Tannehill, A History of the Pioneer Ironworks in Roupes Valley, 1829-1865. Birmingham, Ala.: Jefferson County Historical Commission, 1986.