Governor's Election of 1892

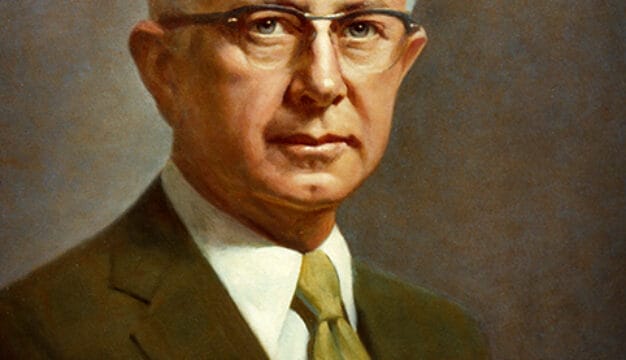

Reuben F. Kolb

The Alabama governor’s election of 1892 was one of the state’s most corrupt electoral contests. The race pitted Reuben F. Kolb, the candidate of a coalition of Jeffersonian Democrats (anti-Bourbon Democrats), the People’s Party (third-party members also known as Populists), and some Republicans, against Thomas Goode Jones, the incumbent Democratic governor. Jones ultimately won the election by stealing votes in the Black Belt counties. Kolb, who ran for the Democratic nomination in 1890, charged Jones and the conservative Bourbon Democrats with using illegal tactics to maneuver him out of that contest and again in 1892, but Alabama did not permit governors’ races to be contested.

Reuben F. Kolb

The Alabama governor’s election of 1892 was one of the state’s most corrupt electoral contests. The race pitted Reuben F. Kolb, the candidate of a coalition of Jeffersonian Democrats (anti-Bourbon Democrats), the People’s Party (third-party members also known as Populists), and some Republicans, against Thomas Goode Jones, the incumbent Democratic governor. Jones ultimately won the election by stealing votes in the Black Belt counties. Kolb, who ran for the Democratic nomination in 1890, charged Jones and the conservative Bourbon Democrats with using illegal tactics to maneuver him out of that contest and again in 1892, but Alabama did not permit governors’ races to be contested.

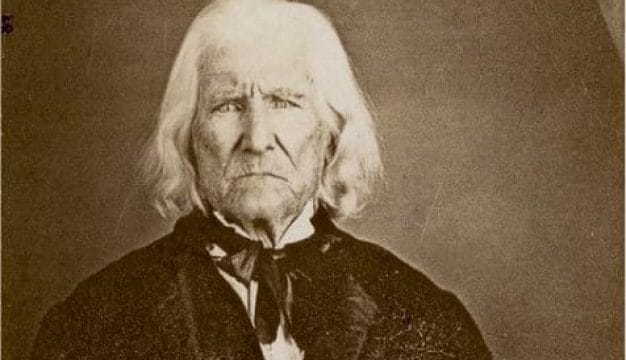

The end of Reconstruction in the mid-1870s saw the rise of Populism, a broad political movement that in Alabama aimed to assist small-scale farmers and laborers against powerful Black Belt planters and industrial interests. Within that movement, various factions had common goals. The Farmers Alliance and the Populist Party supported government regulation of railroads and telegraphs and a plan in which farmers stored crops in federal warehouses to await higher prices. The Jeffersonian Democrats favored a silver-based monetary system, the abolition of the national banking system, a graduated income tax, and an end to convict leasing. In contrast, the Bourbon Democrats (named after the Bourbon Dynasty that was restored in France after the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte) were the largely land- and industry-owning elites who were returned to power when Reconstruction was undermined in the state. They wanted to pursue a conservative fiscal program and maintain white supremacy, the central theme of political, economic, and social life at that time in Alabama. The African American vote was concentrated in 20 south-central Black Belt counties where blacks made up more than half of the population. That voting bloc was crucial to both sides. The Democrats raised the specter of African American domination of the entire state and urged every white man to vote for Jones. Democrats also promoted the Thirteenth Plank in their platform, which promised to maintain white supremacy, whereas Kolb and the Populists warned blacks, as well as poor whites, that they could be disfranchised under Democratic rule.

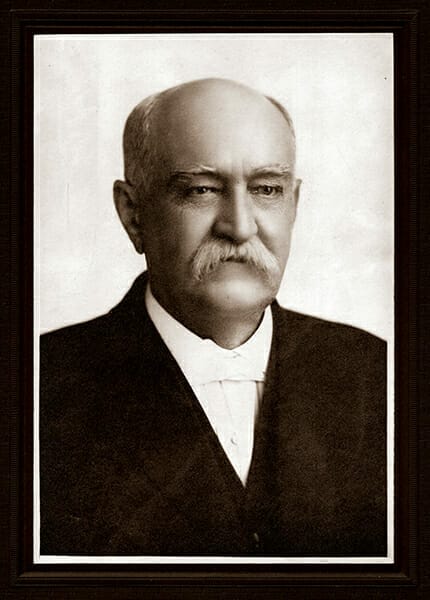

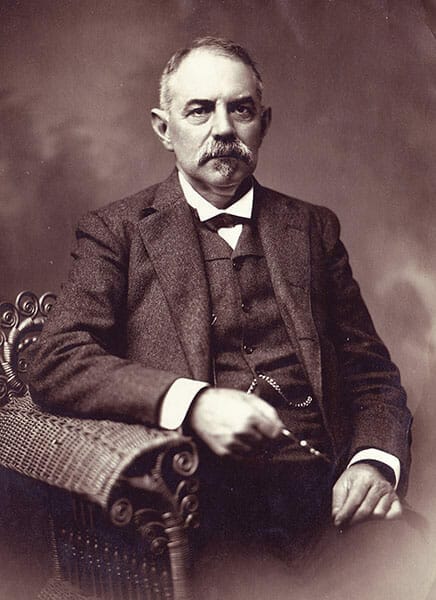

Thomas Goode Jones

In 1892, Kolb was State Commissioner of Agriculture and a leader in the Farmers’ Alliance. He was unwilling to call himself a Populist, although he accepted the endorsement of the People’s Party, and explained that he was the same Democrat he had always been. After losing the nomination to Jones and the Bourbon Democrats, Kolb accepted the call of the Jeffersonian Democrats. As a result, he was able to attract the support of both the Jeffersonian Democrats and third-party Populists who remained separate entities but shared many of the same views and were powerful voices for reform and democracy.

Thomas Goode Jones

In 1892, Kolb was State Commissioner of Agriculture and a leader in the Farmers’ Alliance. He was unwilling to call himself a Populist, although he accepted the endorsement of the People’s Party, and explained that he was the same Democrat he had always been. After losing the nomination to Jones and the Bourbon Democrats, Kolb accepted the call of the Jeffersonian Democrats. As a result, he was able to attract the support of both the Jeffersonian Democrats and third-party Populists who remained separate entities but shared many of the same views and were powerful voices for reform and democracy.

Kolb’s followers included members of the Farmers Alliance, laborers (miners and industrial workers), dissatisfied Democrats, and white and black Republicans. The Alabama Republicans had not even nominated a candidate for governor; their strength was in a few north Alabama counties containing a majority of white voters. Most Republicans supported Kolb, if only to injure the regular Democrats. African Americans in the Black Belt were normally Republicans; they overwhelmingly favored Kolb because he promised to preserve their civil and political rights. But they also were rigidly controlled by the Democrats, who dominated their economic lives and controlled the machinery of government. Jones’s supporters were traditional Democrats, including lawyers, politicians, the press (except for a small and articulate group of reform newspapers), and most wealthy farmers.

Alabamians turned out in large numbers for the August election, with 243,037 ballots cast. Jones received 126,959 votes to Kolb’s 115,524, and 544 ballots were scattered among minor candidates. Jones thus retained the governorship by a margin of 11,445 votes. The voters’ geographical distribution was extremely significant. Jones carried only 29 counties, eight fewer than Kolb. Jones’s strength was divided between 14 white and 15 Black Belt counties. Only eight of his white counties were north of the Black Belt, and there his majority totaled 5,561. Of these only Jefferson County gave him a margin of more than 1,000 votes, and in Morgan County his majority was 11. South of the Black Belt, the governor’s majority in the six counties he carried totaled only 2,139.

The story was entirely different in the Black Belt itself. In 15 counties, Jones defeated Kolb by the runaway margin of 30,117 votes. He received majority votes in Montgomery County (6,254 votes), Dallas County (6,117 votes), and Wilcox County (5,350 votes). Of Kolb’s 37 counties, five were in the Black Belt, where he had a majority of 2,796 votes, whereas his lead in 32 white counties was 23,009. Kolb was strong in every area outside of the Black Belt, but only in Tallapoosa County and Lawrence County did his majority exceed 2,000. Exclusive of the Black Belt’s Democratic-controlled vote, Kolb led Jones by 15,399 votes.

Election abuses took place on a scale not seen since Reconstruction. Ballot boxes with Kolb majorities were stolen after the election. Money, whiskey, and threats were used to influence and change votes. In the Black Belt, returns were announced, then changed and announced again, as the Bourbon Democrat inspectors there permitted open and obvious illegal practices. Fraud also existed beyond the Black Belt, but on a much smaller scale, although in Pike County, collusion between the sheriff and elections officials carried it for Jones. It was patently clear that Jones’s control over local government in the Black Belt had carried him to an election victory. Incongruously, the Democrats had upheld white supremacy by stealing the votes of African Americans in the Black Belt.

Kolb and other reform leaders grumbled and issued threats about seeking redress in the courts or in the state legislature, but because Alabama did not have a law that permitted a governor’s race to be contested, they ultimately could do nothing. Still, all available evidence reveals that Kolb was the legitimately elected governor but was counted out in the Black Belt. Kolb also ran for governor in 1894 and lost that tainted election as well.

At the national and the congressional level, Democrat Grover Cleveland carried Alabama over the Populist James B. Weaver and the Republican Benjamin C. Harrison. The Democrats also carried all of the races for members of the U.S. House of Representatives. Many reformers saw 1892 as only a temporary setback, and the Populists and Jeffersonian Democrats moved toward becoming one party. In response, the Bourbon Democrats, fearful of resurgent populism, rewrote the state’s Constitution in 1901, codifying grandfather clauses, property qualifications, and other measures to disfranchise most African Americans and many poor whites, preserving for themselves political power until civil rights legislation broke that hold in the 1960s.

Additional Resources

Going, Allen. Bourbon Democracy in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1951.

Hackney, Sheldon. Populism to Progressivism in Alabama. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969.

Rogers, William Warren. The One-Gallused Rebellion. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1970.

Webb, Samuel L. Two-Party Politics in the One-Party South: Alabama’s Hill Country, 1874-1920. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997.

Woodward, C. Vann. Origins of the New South, 1877-1913. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971.