Folk Buildings

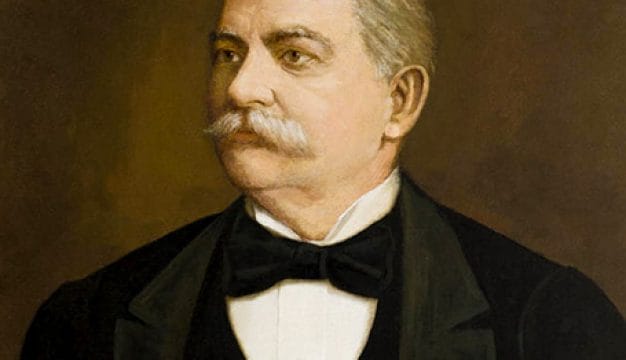

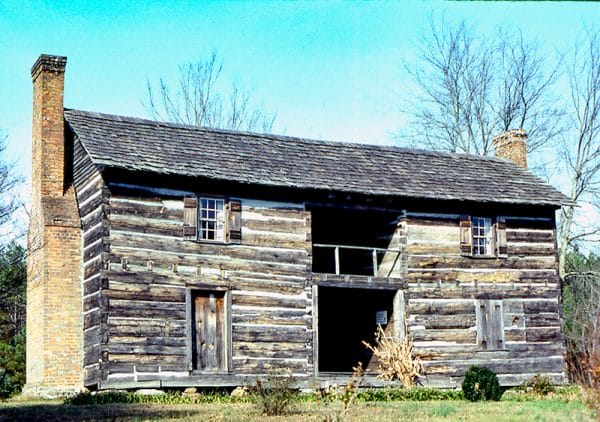

Double-pen House in Chambers County

Folk buildings—constructed from local materials—are the oldest types of structures still standing in Alabama. Built from collective memory, the materials, shapes, sizes, openings, and orientation of the buildings reflect the cultural traditions of the owners and builders. Thus, buildings that shared specific uses looked very similar. Folk building is not architecture in the formal sense of the term, which always refers to some degree to design and construction methods based on drawn plans with the objective of making a unique structure. No two folk houses are exactly alike, however, and each has characteristics that provide information about the individual builders and owners as well as the time of their occupation.

Double-pen House in Chambers County

Folk buildings—constructed from local materials—are the oldest types of structures still standing in Alabama. Built from collective memory, the materials, shapes, sizes, openings, and orientation of the buildings reflect the cultural traditions of the owners and builders. Thus, buildings that shared specific uses looked very similar. Folk building is not architecture in the formal sense of the term, which always refers to some degree to design and construction methods based on drawn plans with the objective of making a unique structure. No two folk houses are exactly alike, however, and each has characteristics that provide information about the individual builders and owners as well as the time of their occupation.

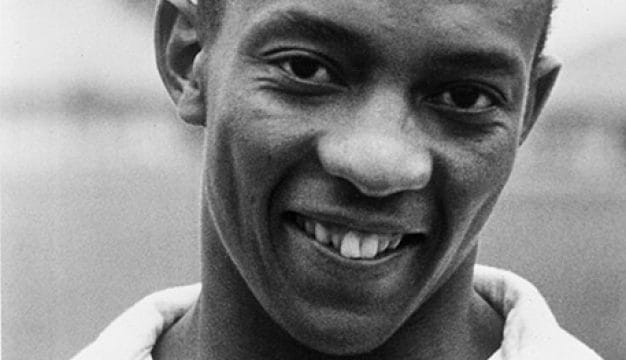

V-shaped Corners

In the early nineteenth century, log construction was the prevailing method in Alabama, and it continued to be employed up to World War II for outbuildings such as sheds and small barns. Five house types, primarily based on early British models, were the most common. All possessed simple side-gable roofs, with the front entrance on a longer side and almost always facing a road. The first type was the single-room, oblong house, generally only about 18×16 feet or 20×16 feet, known as a one-bay, or single-pen, house. The second type—the double house or double-pen—featured two single-pens side by side. The third type also was a double house, but it was characterized by a central hallway, or “dogtrot,” running between the two single houses under a shared roof. The fourth type was a larger one-and-one-half or two-story single house. All four types had exterior side chimneys. The fifth type was a double house of two single pens with a center chimney and was the least common of the group. Timbers in most of the houses of all types were joined at the corners with V-shaped or half-dovetail (so-called for its shape) notching. Roofs were generally covered with shingles or longer boards called shakes. The expedient crude log “cabins” and the more refined houses with neatly shaped wall logs could be built with few tools; an ax was sufficient for most of the labor. Small timbers could be carried by one person, but a horse or mule or neighbors were needed to hoist heavier wall logs, sills, and joists into position.

V-shaped Corners

In the early nineteenth century, log construction was the prevailing method in Alabama, and it continued to be employed up to World War II for outbuildings such as sheds and small barns. Five house types, primarily based on early British models, were the most common. All possessed simple side-gable roofs, with the front entrance on a longer side and almost always facing a road. The first type was the single-room, oblong house, generally only about 18×16 feet or 20×16 feet, known as a one-bay, or single-pen, house. The second type—the double house or double-pen—featured two single-pens side by side. The third type also was a double house, but it was characterized by a central hallway, or “dogtrot,” running between the two single houses under a shared roof. The fourth type was a larger one-and-one-half or two-story single house. All four types had exterior side chimneys. The fifth type was a double house of two single pens with a center chimney and was the least common of the group. Timbers in most of the houses of all types were joined at the corners with V-shaped or half-dovetail (so-called for its shape) notching. Roofs were generally covered with shingles or longer boards called shakes. The expedient crude log “cabins” and the more refined houses with neatly shaped wall logs could be built with few tools; an ax was sufficient for most of the labor. Small timbers could be carried by one person, but a horse or mule or neighbors were needed to hoist heavier wall logs, sills, and joists into position.

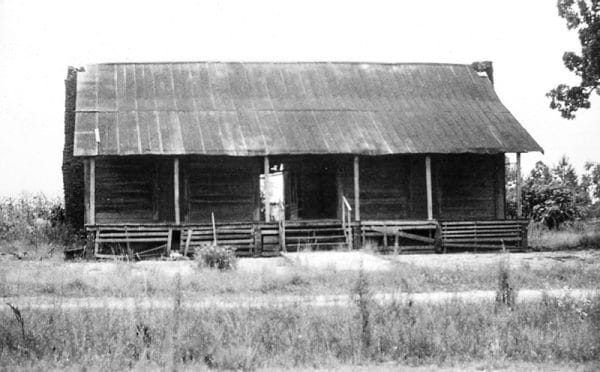

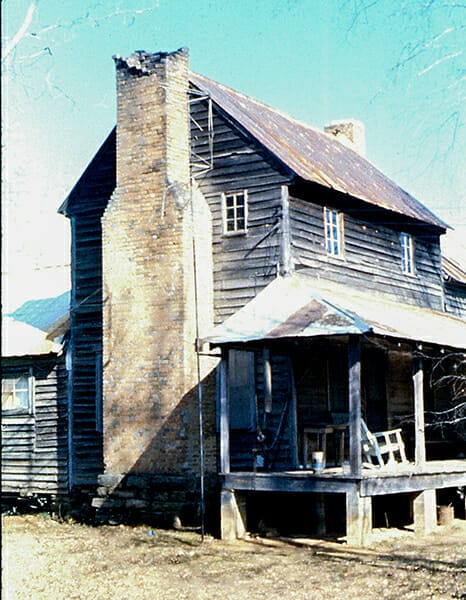

Dogtrot House in Tuscaloosa County

Throughout the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, the central-hall “dogtrot” house became the most widespread type of dwelling in the upland areas inhabited mainly by independent white subsistence farmers. These areas included the Warrior Basin, the hills of central and east Alabama, and the hills and longleaf pine belt of south Alabama. In contrast, the lowlands—comprising the plantation regions of the Tennessee River valley, the central Coosa River valley, and the Black Belt of central Alabama—are closely associated with variations of Georgian and Greek Revival architecture, and the folk house types found there were used primarily for housing enslaved workers, outbuildings, and tenant housing.

Dogtrot House in Tuscaloosa County

Throughout the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, the central-hall “dogtrot” house became the most widespread type of dwelling in the upland areas inhabited mainly by independent white subsistence farmers. These areas included the Warrior Basin, the hills of central and east Alabama, and the hills and longleaf pine belt of south Alabama. In contrast, the lowlands—comprising the plantation regions of the Tennessee River valley, the central Coosa River valley, and the Black Belt of central Alabama—are closely associated with variations of Georgian and Greek Revival architecture, and the folk house types found there were used primarily for housing enslaved workers, outbuildings, and tenant housing.

Central-chimney or “Saddlebag” House

The first permanent influence of European building in Alabama is found in the French settlement at Dauphin Island, at Old Mobile on Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff, on the thinly settled areas along the lower Tombigbee and Alabama rivers, and at the present site of the city of Mobile. Depictions of the early settlements and remaining examples on the coast and in the Mississippi River Valley show the influences from Normandy, France, the former homeland of the many French Canadians who moved to south Alabama. Vernacular, or contract builder, frame houses along the coast reflect traces of French influence with built-in porches and raised piers.

Central-chimney or “Saddlebag” House

The first permanent influence of European building in Alabama is found in the French settlement at Dauphin Island, at Old Mobile on Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff, on the thinly settled areas along the lower Tombigbee and Alabama rivers, and at the present site of the city of Mobile. Depictions of the early settlements and remaining examples on the coast and in the Mississippi River Valley show the influences from Normandy, France, the former homeland of the many French Canadians who moved to south Alabama. Vernacular, or contract builder, frame houses along the coast reflect traces of French influence with built-in porches and raised piers.

Two-story Dogtrot House

Other Alabama folk houses can be traced to Scandinavian settlements on the Delaware Bay, German colonies in Pennsylvania, and British colonies in the Tidewater and Atlantic coast regions. The basic house types were derived from the Middle Ages or earlier and are closely associated with the agricultural system from which we still employ our basic measurements: the foot, yard, rod, acre, and mile. The simple one-room oblong single-pen and the two-pen double houses were borrowed from the English settled colonies. The two-room house with side chimneys and a central hallway has its origins in northern Europe, from the influence of Georgian architecture of the Tidewater, and from the Atlantic coastal region. The great southwestward migration with which these houses were associated followed Indian land cessions as well as innovations and economic changes in cotton-based agriculture. Thus, white subsistence farmers with modest landholdings came southward over several generations from their areas of origin. They brought with them their traditions, including timber construction methods.

Two-story Dogtrot House

Other Alabama folk houses can be traced to Scandinavian settlements on the Delaware Bay, German colonies in Pennsylvania, and British colonies in the Tidewater and Atlantic coast regions. The basic house types were derived from the Middle Ages or earlier and are closely associated with the agricultural system from which we still employ our basic measurements: the foot, yard, rod, acre, and mile. The simple one-room oblong single-pen and the two-pen double houses were borrowed from the English settled colonies. The two-room house with side chimneys and a central hallway has its origins in northern Europe, from the influence of Georgian architecture of the Tidewater, and from the Atlantic coastal region. The great southwestward migration with which these houses were associated followed Indian land cessions as well as innovations and economic changes in cotton-based agriculture. Thus, white subsistence farmers with modest landholdings came southward over several generations from their areas of origin. They brought with them their traditions, including timber construction methods.

Gilchrist House

With the introduction of commercially produced building materials and new framing methods in the 1830s, it became possible to reproduce folk architectural styles with light frame construction covered with horizontal siding, with brick chimneys and corner supports, or piers, and factory-made windows, doors, and hardware. These structures made it possible for the rise of full-time craftsmen, carpenters, or “builders,” who produced houses in popular styles that often mixed or added design elements from various styles and used commercially produced and standardized materials. This stage of folk building is most appropriately termed “commercial vernacular.” It is similar in method to the development of subdivision homes today, although these structures cannot be properly termed “vernacular.”

Gilchrist House

With the introduction of commercially produced building materials and new framing methods in the 1830s, it became possible to reproduce folk architectural styles with light frame construction covered with horizontal siding, with brick chimneys and corner supports, or piers, and factory-made windows, doors, and hardware. These structures made it possible for the rise of full-time craftsmen, carpenters, or “builders,” who produced houses in popular styles that often mixed or added design elements from various styles and used commercially produced and standardized materials. This stage of folk building is most appropriately termed “commercial vernacular.” It is similar in method to the development of subdivision homes today, although these structures cannot be properly termed “vernacular.”

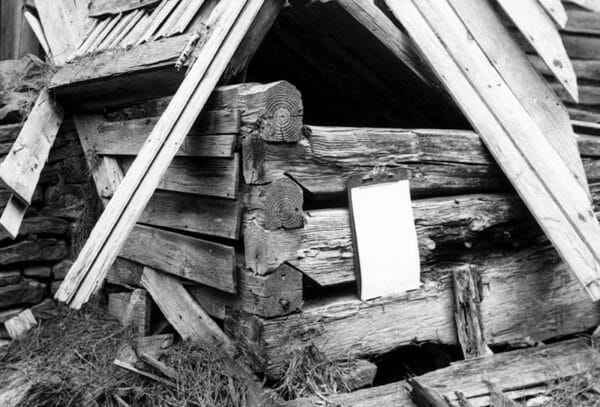

Dogtrot House in Clarke County

Although older log houses are now rare, some could still be found in almost every Alabama county until at least the mid-twentieth century. The frame versions of the older log types completely dominated the upland rural landscape into the 1960s. Now, along the older highways and county roads, few of these relicts of history remain—plain old buildings off in the trees or behind modern houses, sometimes covered with modern metal or plastic siding, sometimes unpainted, and sometimes incorporated into later structures. The few log houses that still exist may be recognized by their low roof pitch, large rock chimneys or rock combined with brick for chimneys and piers, and sometimes by exposed timbers.

Dogtrot House in Clarke County

Although older log houses are now rare, some could still be found in almost every Alabama county until at least the mid-twentieth century. The frame versions of the older log types completely dominated the upland rural landscape into the 1960s. Now, along the older highways and county roads, few of these relicts of history remain—plain old buildings off in the trees or behind modern houses, sometimes covered with modern metal or plastic siding, sometimes unpainted, and sometimes incorporated into later structures. The few log houses that still exist may be recognized by their low roof pitch, large rock chimneys or rock combined with brick for chimneys and piers, and sometimes by exposed timbers.

Further Reading

- Condit, Carl W. American Building. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968.

- Jordan-Bychkov, Terry G. The Upland South: The Making of an American Folk Region. Santa Fe, N.M.: Center for American Places, 2003.

- McAlester, Virginia, and Lee McAlester. A Field Guide to American Houses. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

- Wilson, Eugene M. Alabama Folk Houses. Montgomery: Alabama Historical Commission, 1975.