Patrick J. Lyons

Patrick J. Lyons (1850-1921) served as a city councilman, mayor, and commissioner in Mobile for more than 20 years. As one of Mobile’s most dominant political leaders in the Progressive Era, Lyons helped spur Mobile’s transformation from an aging cotton port to a more commercially diverse city by expanding city boundaries, paving roads, building water and sewage lines, lighting streets, and constructing parks. Despite little formal education, he was also a successful businessman in many areas, most notably as a wholesale grocer. Like other politicians and businessmen of the era, his political and business spheres often collided.

Patrick J. Lyons

Fleeing the potato famine in their native Ireland, Thomas and Johanna Lyons arrived in Mobile in December 1849. Their son Patrick was born in Mobile on January 16, 1850. Raised a Catholic, he attended the Franciscan Brothers School for four years but was orphaned by the age of 10; both of his parents were deceased by around 1860. He then quit school to support his three siblings, a brother and two sisters. At age 13, Lyons signed on as a deckhand aboard riverboats plying the Alabama River. Captain Owen Finnegan, skipper of the Maggie Burke, was impressed with Lyons’s work ethic and apprenticed him as a clerk and riverboat pilot. Finnegan and Lyons later formed a riverboat partnership, the Mobile Trading Company, and Lyons eventually established his own riverboat company. Years on the river provided him with practical business experience and contact with notable Alabama political figures such as Sen. John T. Morgan and also earned him the lifelong title of “Captain.” Lyons never married.

Patrick J. Lyons

Fleeing the potato famine in their native Ireland, Thomas and Johanna Lyons arrived in Mobile in December 1849. Their son Patrick was born in Mobile on January 16, 1850. Raised a Catholic, he attended the Franciscan Brothers School for four years but was orphaned by the age of 10; both of his parents were deceased by around 1860. He then quit school to support his three siblings, a brother and two sisters. At age 13, Lyons signed on as a deckhand aboard riverboats plying the Alabama River. Captain Owen Finnegan, skipper of the Maggie Burke, was impressed with Lyons’s work ethic and apprenticed him as a clerk and riverboat pilot. Finnegan and Lyons later formed a riverboat partnership, the Mobile Trading Company, and Lyons eventually established his own riverboat company. Years on the river provided him with practical business experience and contact with notable Alabama political figures such as Sen. John T. Morgan and also earned him the lifelong title of “Captain.” Lyons never married.

In 1882, Lyons parlayed his riverboat earnings into a partnership in a wholesale grocery business and took sole ownership upon the deaths of his partners. As his grocery business flourished, Lyons purchased other business ventures: foundries, steamship machine shops, a local telephone exchange, a banana importing company, a bank, and a brewery. Although Lyons’s many businesses caused others to accuse him of conflict of interest when he entered politics, he never completely divested himself of his business income.

By the late 1880s, with all of his businesses prospering, Lyons was financially secure enough to seek public office. He first served as an alderman-at-large for several years. His most fortuitous political opportunity appeared in 1895, when popular judge Robert L. Maupin retired as the first ward’s councilman. The first ward of northeast Mobile encompassed the waterfront, railroad yards, and shops, a sizable slice of the commercial district, and the Orange Grove Tract, a working-class neighborhood largely populated by African Americans, Creoles, and Irish immigrants. In his first campaign for councilman in 1897, Lyons billed himself as “a man of the people” and easily won the election, thus laying the foundation for his future political fortunes upon the first ward’s racially diverse population. He also garnered considerable support from other individuals whose offices lay within the first ward, including prominent businessmen, attorneys, and other professionals; many would support Lyons in future mayoral and commission elections.

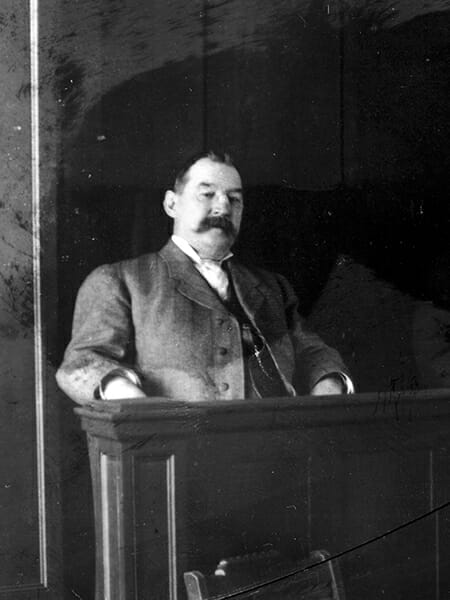

Pat Lyons in Mobile, ca. 1920

During Lyons’s service as councilman, political control in Mobile was vested in the shared appointive powers of the mayor and the council. He learned many important political lessons during his councilman’s tenure between 1897 and 1903 and quickly grasped the importance of providing his constituents with improved utilities, paved streets, and new streetcar lines. Lyons witnessed how the mayor and the council relied upon appointments and patronage to maintain control over the city. He also cultivated alliances with leaders of Mobile’s “Big Four,” which consisted of the county tax collector, tax assessor, circuit court clerk, and probate judge. The influence of this political machine extended throughout the city and county and to the governor’s office. After 1900, the “Big Four” became indistinguishable from Lyons’s political machine.

Pat Lyons in Mobile, ca. 1920

During Lyons’s service as councilman, political control in Mobile was vested in the shared appointive powers of the mayor and the council. He learned many important political lessons during his councilman’s tenure between 1897 and 1903 and quickly grasped the importance of providing his constituents with improved utilities, paved streets, and new streetcar lines. Lyons witnessed how the mayor and the council relied upon appointments and patronage to maintain control over the city. He also cultivated alliances with leaders of Mobile’s “Big Four,” which consisted of the county tax collector, tax assessor, circuit court clerk, and probate judge. The influence of this political machine extended throughout the city and county and to the governor’s office. After 1900, the “Big Four” became indistinguishable from Lyons’s political machine.

Between 1897 and 1904, Lyons served four two-year terms as the first ward’s councilman. He consolidated his political base in the first ward, formed alliances with other councilmen and aldermen-at-large, and acquired supporters from across the city. In 1903, the city council chose Lyons as its president under the terms of the newly drafted City Charter of 1903, which also stated that the council president would serve as mayor pro tempore. Lyons became mayor in July 1904 when Charles E. McLean died and successfully won mayoral elections in 1906, 1908, and 1910.

During his first term as mayor in 1904, Lyons authorized contracts for upgraded utilities, paving, and streetcar lines for the entire city. He also ordered the construction of a municipal waterworks that would bring an inexpensive, sanitary water supply to the city. To beautify the city and provide recreational opportunities, Lyons embarked on an ambitious public parks program that featured improvements to Bienville Square, lighting for Washington Square, and construction of a new playground on the western boundary of Church Street Cemetery. He devoted much of his time during his first two terms as mayor, however, to the conversion of the old Stein Reservoir property in Spring Hill into the park that later bore his name. By 1915, Lyons Park was attracting city residents of all ages.

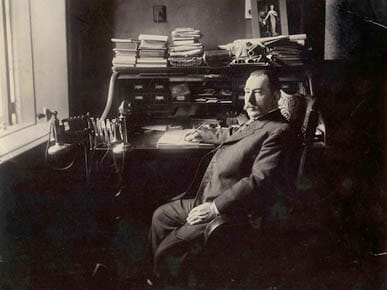

Pat Lyons in Mobile Mayor’s Office, 1913

Still, Lyons’s plans to modernize the city were hampered by a debt of more than $2 million dating back to the Reconstruction Era. In June 1905, he tried to refinance the debt through a bond issue, but legal technicalities and old bondholders demanding immediate repayment prevented the issue; the city was on the verge of default by December. To avoid default, Lyons in 1907 turned to Edward J. Buck, president of the Mobile City Bank and Trust Company. Lyons at that time was the bank’s vice president and a board member. He and Buck lobbied the legislature for a new debt refunding act, which was approved and later signed into law. The bond issue prevented the city’s financial collapse, but questions persisted about Lyons’s reliance on Buck and his own business connections to solve the fiscal crisis.

Pat Lyons in Mobile Mayor’s Office, 1913

Still, Lyons’s plans to modernize the city were hampered by a debt of more than $2 million dating back to the Reconstruction Era. In June 1905, he tried to refinance the debt through a bond issue, but legal technicalities and old bondholders demanding immediate repayment prevented the issue; the city was on the verge of default by December. To avoid default, Lyons in 1907 turned to Edward J. Buck, president of the Mobile City Bank and Trust Company. Lyons at that time was the bank’s vice president and a board member. He and Buck lobbied the legislature for a new debt refunding act, which was approved and later signed into law. The bond issue prevented the city’s financial collapse, but questions persisted about Lyons’s reliance on Buck and his own business connections to solve the fiscal crisis.

The debt crisis was not the only instance in which Lyons’s business interests became entangled in city governance and politics. In 1907, an Etowah County legislator introduced a bill prohibiting the sale of liquor outside of incorporated cities and towns. Because this bill was widely supported, Lyons feared for his wholesale liquor business and brewery. Moreover, he wanted city police to enforce any liquor laws rather than the county sheriff and his deputies, who reported to the governor. Debate over the liquor issue intensified, but Lyons carefully avoided a direct confrontation with Gov. B. B. Comer over Prohibition. Lyons enforced the nine o’clock closing regulation for saloons and other minor provisions of the state Prohibition law, but violators escaped severe punishment. By 1909, Mobile policemen seldom arrested saloonists who ignored the closing order.

Lyons shrewdly used surrogates to undermine the governor and Prohibition. Three Mobile & Ohio Railroad officials closely associated with Lyons publicly delivered the mayor’s message against Prohibition. Lyons, in turn, quietly organized local opposition to the governor’s call for a special legislative session to regulate railroad rates. With most residents and city officials in agreement with Lyons on the liquor issue, Prohibition, like state bans on Sunday baseball, vaudeville, and movies, went unheeded. Lyons correctly gauged public sentiment on Prohibition and used this issue as another means of solidifying his political control.

First Meeting of the Mobile City Commission

Although Lyons was periodically challenged by prohibitionists and political reform factions, his machine consistently turned out his supporters on election day. The most serious challenge to Lyons occurred in 1910-11 as reformers across the nation tried to sweep aldermanic officials from power under a commission government plan. Championed by its supporters as a way to end the corruption, cronyism, and inefficiency in municipal governments, this plan called for replacing the council and mayor with three commissioners. The commissioners, with one member rotating as mayor, shared the duties formerly exercised by the councilmen. The Progressive Association, an influential coalition of businessmen and professionals, led the pro-commission fight in Mobile, whereas the plan’s primary opponents were serving in the municipal government. The bitter struggle over the plan shattered old political alliances and long friendships. For example, two of Lyons’s closest friends and strongest allies, banker Edward J. Buck and Mobile Register editor Erwin Craighead, were vocal leaders among the pro-commission forces.

First Meeting of the Mobile City Commission

Although Lyons was periodically challenged by prohibitionists and political reform factions, his machine consistently turned out his supporters on election day. The most serious challenge to Lyons occurred in 1910-11 as reformers across the nation tried to sweep aldermanic officials from power under a commission government plan. Championed by its supporters as a way to end the corruption, cronyism, and inefficiency in municipal governments, this plan called for replacing the council and mayor with three commissioners. The commissioners, with one member rotating as mayor, shared the duties formerly exercised by the councilmen. The Progressive Association, an influential coalition of businessmen and professionals, led the pro-commission fight in Mobile, whereas the plan’s primary opponents were serving in the municipal government. The bitter struggle over the plan shattered old political alliances and long friendships. For example, two of Lyons’s closest friends and strongest allies, banker Edward J. Buck and Mobile Register editor Erwin Craighead, were vocal leaders among the pro-commission forces.

With many of his friends, including most of the city’s wholesale merchants, supporting the commission and virtually the entire council on the other side, Lyons was in a very precarious political position. Whereas he adamantly opposed the plan, he ultimately assumed a neutral public stance. He had built his powerful ward-based machine as a councilman and mayor and was reluctant to jeopardize it in the name of any so-called and possibly fleeting reform movement. He also was keenly aware of the commission plan’s public popularity and feared being labeled as an opponent. Lyons, however, had a political safety net available. If Mobile’s voters adopted the plan, they then would elect two commissioners and the third man by law would be Lyons, the incumbent mayor.

On June 5, 1911, Mobilians overwhelmingly adopted the commission government. While the jubilant Progressive Association leaders celebrated the election as the dawn of a new era of political reform and commercial prosperity in Mobile, Lyons and his friends privately doubted how three commissioners could adequately provide the municipal services demanded by residents of the city’s individual wards. Such doubts—along with the election of two inexperienced commissioners and the typical political infighting inherent in municipal government—undermined Mobile’s progress for some years.

Pat J. Lyons, ca. 1914

As commissioner, Lyons did not significantly alter his mayoral style, but still relied heavily on patronage and appointments. He continued to emphasize providing highly visible municipal services to the electorate, especially electricity, sanitary water and sewage lines, storm drains, streetcar lines, police and fire stations, and public parks. Lyons generally ignored reformers’ demands to enforce Prohibition and abolish Mobile’s notorious “restricted district” where Prohibition had been tolerated since Reconstruction. But he found that he could no longer enforce his will on municipal affairs using the council as a political buffer against public criticism as he had in the past. On the eve of World War I, public outcries of corruption, incompetency, and nepotism were leveled at city government, particularly the police and fire departments.

Pat J. Lyons, ca. 1914

As commissioner, Lyons did not significantly alter his mayoral style, but still relied heavily on patronage and appointments. He continued to emphasize providing highly visible municipal services to the electorate, especially electricity, sanitary water and sewage lines, storm drains, streetcar lines, police and fire stations, and public parks. Lyons generally ignored reformers’ demands to enforce Prohibition and abolish Mobile’s notorious “restricted district” where Prohibition had been tolerated since Reconstruction. But he found that he could no longer enforce his will on municipal affairs using the council as a political buffer against public criticism as he had in the past. On the eve of World War I, public outcries of corruption, incompetency, and nepotism were leveled at city government, particularly the police and fire departments.

The deteriorating situation within the commission climaxed in the fall of 1917. Relying on the authority of the current mayor, George E. Crawford, Lyons orchestrated the removal of more than one-third of the police force and many other city employees. However, he protected his brother Thomas Lyons from dismissal as a clerk in the Southern Market. On October 4, 1917, John Duff, a former policeman whose saloon license bad been revoked by Lyons, attacked the commissioner as he waited for a streetcar at the corner of Royal and Dauphin Streets. Lyons received a deep wound over his left eye and severe bruises on his head, but his injuries were not life-threatening. Shaken emotionally, Lyons realized that regardless of his lengthy service to the city, he was no longer universally respected and revered by Mobilians. Lyons died on September 2, 1921, and was buried in the Catholic Cemetery of Mobile.

Further Reading

- Alsobrook, David E. “Alabama Port City: Mobile during the Progressive Era, 1896-1917.” Ph.D. diss. Auburn University, 1983, 42-85.

- ———. “Boosters, Moralists, and Reformers: Mobile’s Leadership during the Progressive Era, 1895-1920.” Alabama Review 55 (April 2002), 135-50.

- ———. “Mobile’s Commission Government Campaign of 1910-1911.” Alabama Review 44 (Jan.1991), 36-60.