Native American Foodways

Native American Foods

When Europeans first began to arrive in North America in about 1500, Native Americans in the Southeast were acquiring most of their food through agriculture, supplemented by hunting and gathering wild foods. This diet was in place in Alabama by the Mississippian period (AD 1000-1500) and it became the general diet of most of the southeastern Indian groups until well into the historic period. The crops that formed the foundation of this traditional Native American diet were the “three sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—a combination of foods that provides most of the essential vitamins, nutrients, and calories of a healthy diet. Most Europeans at the time did not enjoy such a beneficial diet and thus most European explorers were greatly impressed by the height, strength, and general health of the Native Americans they encountered. Over time, the Europeans and Africans who came to populate the Southeast adopted many aspects of this diet as well.

Native American Foods

When Europeans first began to arrive in North America in about 1500, Native Americans in the Southeast were acquiring most of their food through agriculture, supplemented by hunting and gathering wild foods. This diet was in place in Alabama by the Mississippian period (AD 1000-1500) and it became the general diet of most of the southeastern Indian groups until well into the historic period. The crops that formed the foundation of this traditional Native American diet were the “three sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—a combination of foods that provides most of the essential vitamins, nutrients, and calories of a healthy diet. Most Europeans at the time did not enjoy such a beneficial diet and thus most European explorers were greatly impressed by the height, strength, and general health of the Native Americans they encountered. Over time, the Europeans and Africans who came to populate the Southeast adopted many aspects of this diet as well.

A vegetable-rich diet had been common among Native Americans for centuries. Even the Paleoindians, despite their reputation as big-game hunters, probably received most of their daily nutrition from gathering. This predominantly vegetable diet was particularly characteristic of the Archaic period, during which Indian groups made yearly rounds of hunting and gathering sites for seasonal foods. Late in Archaic times there was a slow move to rudimentary horticulture of local food plants such as lambsquarters, sunflowers, and (perhaps) squash. Horticulture intensified in the Woodland period, and most Native American populations began living in villages near their fields. In about AD 800, corn and beans spread from Mexico into the Mississippi Valley, and by about AD 1000, the Mississippian culture was established in Alabama.

The Three Sisters

Squashes and pumpkins, which probably spread from Mexico, were the first plants that southeastern Indians domesticated. Native Americans developed many varieties of squashes, but common yellow squash, winter squashes, and pumpkins—especially valued for their sweetness and flavor—were the most popular. Pumpkins and winter squashes, which provided important vitamins, could be stored for long periods in cold weather and also could be dried for later consumption. Several varieties of gourds, hard-shelled members of the squash family, were cultivated and dried to use as containers and utensils.

Beans were an excellent protein source and added additional nutrients to the diet. In addition to green beans, consumed in their tender husks, speckled, kidney, and white beans were the most common varieties. When dried, beans were stripped from their husks and stored in baskets, gourds, and ceramic pots. Fresh green beans were snapped and strung with a needle and thread. Dried in the rafters of the house, these strings of beans were called “leather-britches” by Europeans. They were put into water and reconstituted by lengthy cooking with a bit of fat or meat added for flavor—perhaps the origin of the southern custom of overcooked green beans. Beans were cooked, dried, mixed with cornmeal, or even ground to make bean meal or flour.

Creek Re-enactors and Village

Corn, however, was the primary food of Native Americans throughout much of North America and supplied most of the calories in their diet. There are more than 20 different types, including popcorn, as well as many colors. White corn was preferred in the Southeast. The large multicolored corn seen for sale in the fall as “Indian corn” is a modern variety. True Indian corn is small, like popcorn. Native Americans sometimes ate fresh corn, but they usually boiled or roasted it. The southeastern Indian new year began with the busk or Green Corn Ceremony, an important and elaborate mid-summer festival held to celebrate the ripening of the first corn. Thereafter, several varieties of corn ripened in sequence and extended the harvest until late fall. The dried ears were stored in carefully maintained, elevated, basket-like cribs sealed with mud. Dried corn was cracked in a wooden mortar with a pestle to make corn flour, cornmeal, and grits. Or it was soaked in water and wood ashes (a source of lye) to separate and break down the difficult-to-digest husk and then boiled to make hominy. Interestingly, the addition of the ashes not only made the corn more digestible, it released niacin, an essential vitamin. Europeans adopted the corn diet, but not the addition of alkaline ashes, and people who ate a corn-rich diet, particularly poor southerners, suffered from pellagra (vitamin B deficiency) into modern times.

Creek Re-enactors and Village

Corn, however, was the primary food of Native Americans throughout much of North America and supplied most of the calories in their diet. There are more than 20 different types, including popcorn, as well as many colors. White corn was preferred in the Southeast. The large multicolored corn seen for sale in the fall as “Indian corn” is a modern variety. True Indian corn is small, like popcorn. Native Americans sometimes ate fresh corn, but they usually boiled or roasted it. The southeastern Indian new year began with the busk or Green Corn Ceremony, an important and elaborate mid-summer festival held to celebrate the ripening of the first corn. Thereafter, several varieties of corn ripened in sequence and extended the harvest until late fall. The dried ears were stored in carefully maintained, elevated, basket-like cribs sealed with mud. Dried corn was cracked in a wooden mortar with a pestle to make corn flour, cornmeal, and grits. Or it was soaked in water and wood ashes (a source of lye) to separate and break down the difficult-to-digest husk and then boiled to make hominy. Interestingly, the addition of the ashes not only made the corn more digestible, it released niacin, an essential vitamin. Europeans adopted the corn diet, but not the addition of alkaline ashes, and people who ate a corn-rich diet, particularly poor southerners, suffered from pellagra (vitamin B deficiency) into modern times.

Fresh corn was mixed with beans, squash, and other ingredients to make vegetable stews. Corn flour and meal was mixed with bear fat and cooked on a hot hearth rock to make cakes. The most common southeastern Indian dish was a thick cracked-corn soup called sofkee. A large pot of sofkee almost always stood by most home fires, and everyone was invited to reach into it with a ladle-like wooden spoon and eat their fill. Sofkee often had other ingredients, like pieces of meat or fish, in which case it was called sofkee-nitkee—”sofkee with bits.”

It is hard to over-emphasize the importance of corn in southeastern Indian life. Corn (properly maize) was introduced into the Mississippi Valley from Mexico about AD 800. It was a revolutionary food that for the first time allowed Native Americans (who had been practicing rudimentary horticulture for several thousand years) to store up reliable food surpluses. The resulting leap in population and cultural complexity became known as the Mississippian period, which dominated the Southeast and Midwest until after the European conquest. Indeed, even after the collapse of the Mississippian culture in the sixteenth century, the historic Indian diet was substantially the same as the Mississippian diet.

Native American Agriculture

In the South, cornfields belonged to and were worked by women, but men helped clear land and harvest the crop. Indians cultivated fields with a hoe and a digging stick, rather than a plow. Townspeople worked the earth into hills, and then planted the “three sisters” in the same hill. The corn stalks supported the beans, and the squash ran between the hills. Because the fields were located in the lowlands, often at some distance from the town, they were guarded from birds and animals by children and old people perched on elevated platforms, especially as harvest neared.

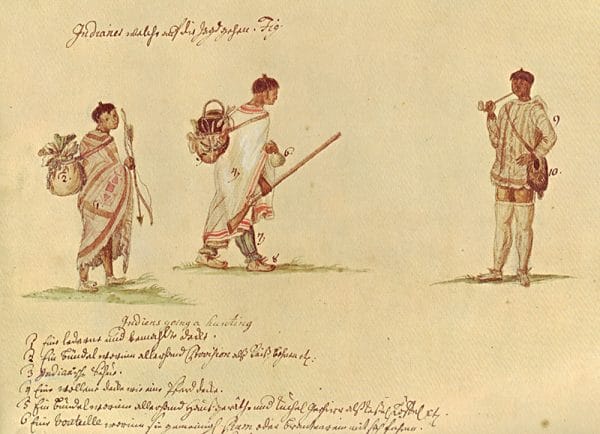

Yuchis Going Hunting

Hunting and fishing supplemented the main diet. Meat provided additional protein and nutritive variety and was greatly sought, but it was not as prevalent a part of the traditional southeastern Indian diet as it is in the modern American diet. It was, however, an important activity for men and boys, allowing them to acquire extra food and accrue status and training for warfare. Deer, turkeys, small birds and mammals, fish, mussels, crayfish, and turtles found their way into the pot. Deer meat, an important food, also was dried into jerky on racks over smoky fires.

Yuchis Going Hunting

Hunting and fishing supplemented the main diet. Meat provided additional protein and nutritive variety and was greatly sought, but it was not as prevalent a part of the traditional southeastern Indian diet as it is in the modern American diet. It was, however, an important activity for men and boys, allowing them to acquire extra food and accrue status and training for warfare. Deer, turkeys, small birds and mammals, fish, mussels, crayfish, and turtles found their way into the pot. Deer meat, an important food, also was dried into jerky on racks over smoky fires.

Despite falling into disrepute in modern times, fat was and remains an important part of the diet. Although deer meat is an excellent source of protein, it has little fat. Bears, on the other hand, boast large amounts of fat and were highly prized. They were hunted in special areas set aside for that purpose in the fall when they were at their fattest. Early European traders and visitors agreed that bear ribs, barbequed and dripping with fat, were the best meat on the frontier. Bear fat was carefully collected and saved. Traditionally, it was the most important source of cooking oil and had numerous other uses, including paint-mixing and repelling mosquitoes when spread on the skin.

The Native Americans gathered seasonal wild foods to supplement the “three sisters.” Among the fruits and seeds were sunflower, amaranth, honey locust, crabapples and haws, persimmons, plums, grapes, and paw-paws. Berries included: blackberries, huckleberries, blueberries, mulberries, elderberries and strawberries. Important nuts included hickory nuts, chestnuts, and white oak acorns. Hickory nuts were processed by the bushel to make flour nut meal and oil making them a particularly valuable foodstuff. Pecans originated in the Mississippi Valley and were not commonly cultivated in the Southeast until the late nineteenth century. Black walnuts and butternuts are indigenous to North America as are such native roots as wild sweet potatoes (“man-root” or “man-o-the-woods”), arrowroot, greenbriar (also known popularly as “smilax,” and “coontie” by the area’s Native Americans), and cattails. Important leaves and stems included pokeweed, bay, indigenous mints, sorrel, sassafras, and yaupon holly.

As contact with the Europeans increased, Indians quickly adopted new foods from Europe, Africa, and Central and South America. Oranges were introduced by the Spanish and grew wild throughout the frost-free areas of the South by the eighteenth century. The Indians also quickly adopted peaches and some towns boasted orchards with as many as 300 trees. Peanuts are South American in origin but became so common in Africa that they are widely believed to be native there. Peanuts, as well as Central American sweet potatoes (batatas), were taken to Africa by the Spanish as food for slaves and were introduced from there into southeastern Indian gardens. The potato was first domesticated by the Andean Indians and brought back to Europe as early as 1570 by Spanish explorers. Potatoes grew well in the cool European climate and were introduced to North America by the British, French, and northern Europeans. Also new to Indian gardens were several varieties of field peas from Africa, okra (also from Africa), and varieties of Asian cultivated rice.

Sweets were generally an imported treat. Brown sugar, syrup, and molasses are derived from African sugar cane. Honey became common only after honeybees were introduced to America from Europe. Edible melons and cucumbers are native to the Old World but came to America early. Cucumbers and watermelons (originally with white flesh) were common in historic Indian gardens.

As people of African and European descent adopted Native American foods, so did Native Americans adopt African and European foods. Today, the typical modern Indian diet has come to be characterized by many of the unhealthy aspects of the mainstream American diet. Because modern Indian groups tend to be poor, their diets resemble those of poor blacks and whites, meaning that they tend to be heavy in fats and starches, with all the concomitant dangers of obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes. Indeed, the disproportionate prevalence of diabetes in the Indian population may have its roots in the introduction of fatty meats into to a population long adapted to a low-fat diet. Leaders of several Indian nations in the United States have advocated a return to traditional foods as a means to combat these ills.

Modern southern diets include a broad selection of Indian dishes. Hominy, grits, sweet potatoes, and many other foods are the legacy of the region’s Indian peoples. Indeed, the “traditional” American thanksgiving dinner of turkey, cornmeal stuffing, green beans, wild rice, mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes, squash, pumpkin pie, grits, cornbread, green beans, pinto beans, tomatoes and peppers all come from Native Americans.

Further Reading

- Blejwas, Emily. The Story of Alabama in Fourteen Foods. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2019.

- Hudson, Charles. The Southeastern Indians. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1976.