Joseph Wheeler

Joseph Wheeler

Joseph Wheeler (1836-1906) served as the commander of cavalry for the Confederate Army of Tennessee during the Civil War, then went on to a career as a member of Congress from Alabama before returning to the military during the Spanish-American War. Promoted to major general at age 26, he became the only Confederate corps commander to later hold the same position in the U.S. Army. His small stature and sometimes eccentric behavior made him a colorful figure, but it was his record on the battlefield that won him the nickname “Fightin’ Joe Wheeler.” His home, Pond Spring, in Hillsboro, Lawrence County, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is maintained by the Alabama Historical Commission.

Joseph Wheeler

Joseph Wheeler (1836-1906) served as the commander of cavalry for the Confederate Army of Tennessee during the Civil War, then went on to a career as a member of Congress from Alabama before returning to the military during the Spanish-American War. Promoted to major general at age 26, he became the only Confederate corps commander to later hold the same position in the U.S. Army. His small stature and sometimes eccentric behavior made him a colorful figure, but it was his record on the battlefield that won him the nickname “Fightin’ Joe Wheeler.” His home, Pond Spring, in Hillsboro, Lawrence County, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is maintained by the Alabama Historical Commission.

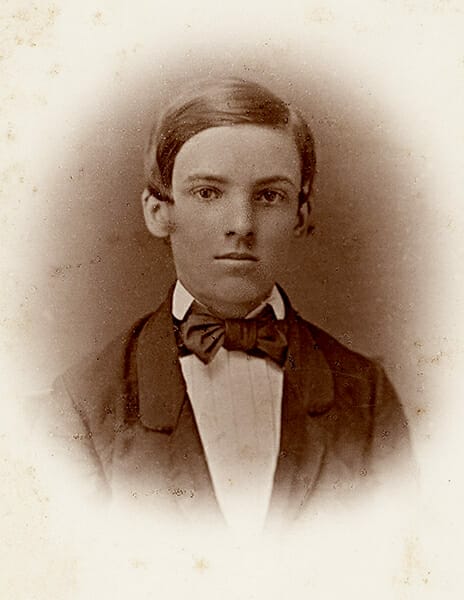

Joseph Wheeler, ca. 1855

Born on September 10, 1836, in Augusta, Georgia, to parents originally from New England, Wheeler seemed destined for a career as a merchant like his father Joseph Wheeler Sr., who was a banker, cotton broker, and real estate speculator before being ruined in the economic depression that followed the Panic of 1837. When his wife Julia Hull died, the elder Wheeler returned home to Connecticut with his children. A few years later, further financial setbacks forced him to move back to Georgia, but his youngest son stayed with relatives in Connecticut to continue his education at the Episcopal Academy in Cheshire. Later, the younger Wheeler moved to New York to live with an older sister who had married a prominent businessman. Rather than become a businessman himself, Wheeler chose a career as a soldier and was admitted to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1854 at the age of 17. He graduated near the bottom of his class in 1859 and was posted to the cavalry school at Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania. A few months later, second lieutenant Wheeler moved to New Mexico as an officer in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles at Fort Craig. Sent to accompany a wagon train from Missouri to Santa Fe, Wheeler saw his first action in a skirmish against a small force of Native Americans.

Joseph Wheeler, ca. 1855

Born on September 10, 1836, in Augusta, Georgia, to parents originally from New England, Wheeler seemed destined for a career as a merchant like his father Joseph Wheeler Sr., who was a banker, cotton broker, and real estate speculator before being ruined in the economic depression that followed the Panic of 1837. When his wife Julia Hull died, the elder Wheeler returned home to Connecticut with his children. A few years later, further financial setbacks forced him to move back to Georgia, but his youngest son stayed with relatives in Connecticut to continue his education at the Episcopal Academy in Cheshire. Later, the younger Wheeler moved to New York to live with an older sister who had married a prominent businessman. Rather than become a businessman himself, Wheeler chose a career as a soldier and was admitted to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1854 at the age of 17. He graduated near the bottom of his class in 1859 and was posted to the cavalry school at Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania. A few months later, second lieutenant Wheeler moved to New Mexico as an officer in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles at Fort Craig. Sent to accompany a wagon train from Missouri to Santa Fe, Wheeler saw his first action in a skirmish against a small force of Native Americans.

When secession came in the aftermath of Abraham Lincoln’s election as president in 1860, Wheeler resigned his commission in the U.S. Army. Despite his New England roots and time spent in the North, his loyalty lay with Georgia. His brother, William, wrote to Georgia governor Joseph E. Brown offering the cavalry officer’s services to the state, and Joe Wheeler became a lieutenant first in the Georgia militia and then the Confederate Army.

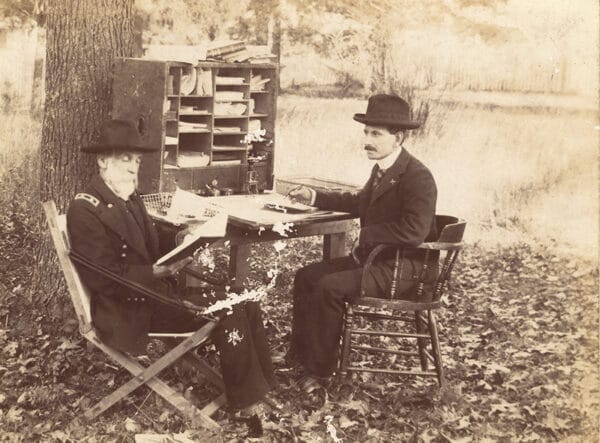

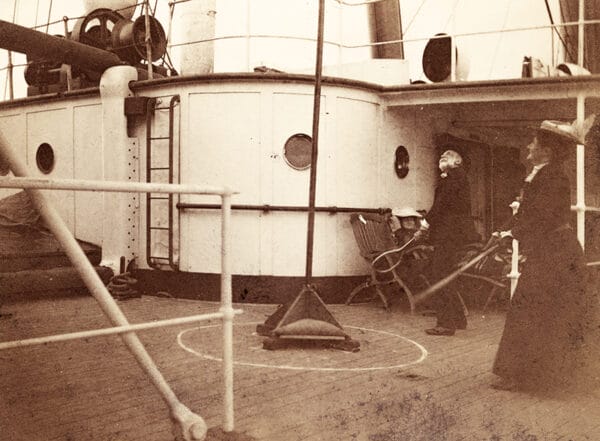

Joseph Wheeler and Family, 1896

Assigned to help construct coastal defenses at Pensacola Bay, Wheeler soon attracted the attention of General Braxton Bragg, his commander in the region. Wheeler’s performance brought a promotion from lieutenant to colonel while he helped build forts, place batteries, and train recruits. Bragg’s pride and somewhat prickly personality led to many difficulties with his officers, but Wheeler’s unassuming manner and professional conduct won him Bragg’s trust and loyalty. When Bragg took command of the Army of Tennessee, Wheeler became one of his most reliable subordinates.

Joseph Wheeler and Family, 1896

Assigned to help construct coastal defenses at Pensacola Bay, Wheeler soon attracted the attention of General Braxton Bragg, his commander in the region. Wheeler’s performance brought a promotion from lieutenant to colonel while he helped build forts, place batteries, and train recruits. Bragg’s pride and somewhat prickly personality led to many difficulties with his officers, but Wheeler’s unassuming manner and professional conduct won him Bragg’s trust and loyalty. When Bragg took command of the Army of Tennessee, Wheeler became one of his most reliable subordinates.

Initially given command of the Nineteenth Alabama Infantry Regiment, Wheeler demonstrated his abilities as an officer at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. Although his troops played a supporting role in the early part of the engagement, Wheeler’s regiment fought well, despite losing one third of its number as casualties. When the tide of the battle turned against the Confederates, Wheeler was given command of the rear guard that covered the army’s retreat. During Bragg’s invasion of Kentucky in the summer of 1862, Wheeler again performed well, this time as a brigade commander. In August, he was shifted to the cavalry, the role for which he had been trained and where his talents and passion lay. In October 1862, he was made chief of cavalry for the Army of Tennessee and soon after received a promotion to brigadier general.

Joe Wheeler Statue at U.S. Capitol

Wheeler excelled in cooperating with, and supporting, the main army. He displayed his greatest skills in screening the army’s movements, supporting the infantry during battles, and especially in covering retreats, a skill that earned him the rank of major general. A professional to the core, he carried out his orders to the letter and carefully followed regulations. In fact, he authored several military manuals, including Cavalry Tactics in 1863, which became the standard for Confederate cavalry operations. In it, Wheeler outlined a modern approach to the cavalry, as he fully adopted the model of the mounted infantry. Unlike heavy cavalry or dragoons, both of which fought on horseback, the mounted infantry combined the speed and scouting abilities of the cavalry with the firepower of the infantry. Horses enabled them to move quickly into a position, where they then dismounted and fought as infantry. This combination proved ideal for operations in the heavily wooded and mountainous regions of the South and remained the American model for decades afterward. Although Wheeler did not create the mounted infantry model, he did recognize its effectiveness and did his best to both promote and implement it in the field.

Joe Wheeler Statue at U.S. Capitol

Wheeler excelled in cooperating with, and supporting, the main army. He displayed his greatest skills in screening the army’s movements, supporting the infantry during battles, and especially in covering retreats, a skill that earned him the rank of major general. A professional to the core, he carried out his orders to the letter and carefully followed regulations. In fact, he authored several military manuals, including Cavalry Tactics in 1863, which became the standard for Confederate cavalry operations. In it, Wheeler outlined a modern approach to the cavalry, as he fully adopted the model of the mounted infantry. Unlike heavy cavalry or dragoons, both of which fought on horseback, the mounted infantry combined the speed and scouting abilities of the cavalry with the firepower of the infantry. Horses enabled them to move quickly into a position, where they then dismounted and fought as infantry. This combination proved ideal for operations in the heavily wooded and mountainous regions of the South and remained the American model for decades afterward. Although Wheeler did not create the mounted infantry model, he did recognize its effectiveness and did his best to both promote and implement it in the field.

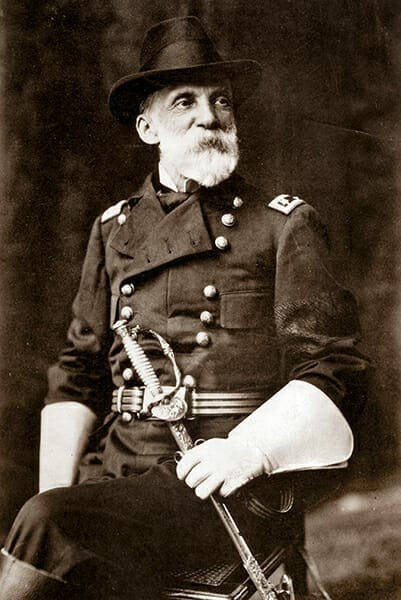

Joseph Wheeler, ca. 1898

Wheeler did not perform well as a raider, a skill that brought fame to many other cavalry commanders, including both Nathan Bedford Forrest and J. E. B. Stuart. His raids often ended disastrously, and he did not enjoy the notoriety that came in that area. Later in the war, Wheeler’s cavalry often put up the only defense the South could offer against the invading forces of William Tecumseh Sherman. Unsuccessful in stopping the invasion, he nevertheless won many small battles along the way. Wheeler also volunteered to cover the retreat of Confederate president Jefferson Davis in the chaotic days at the end of the war. Although he could not prevent the capture of Davis, Wheeler accompanied him to prison and remained in solitary confinement until his release in the summer of 1865.

Joseph Wheeler, ca. 1898

Wheeler did not perform well as a raider, a skill that brought fame to many other cavalry commanders, including both Nathan Bedford Forrest and J. E. B. Stuart. His raids often ended disastrously, and he did not enjoy the notoriety that came in that area. Later in the war, Wheeler’s cavalry often put up the only defense the South could offer against the invading forces of William Tecumseh Sherman. Unsuccessful in stopping the invasion, he nevertheless won many small battles along the way. Wheeler also volunteered to cover the retreat of Confederate president Jefferson Davis in the chaotic days at the end of the war. Although he could not prevent the capture of Davis, Wheeler accompanied him to prison and remained in solitary confinement until his release in the summer of 1865.

Joseph Wheeler during the Spanish-American War

After the war, Wheeler married Daniella Jones Sherrod, a widow whom he had met while fighting in northern Alabama. The couple would have seven children. He tried his hand at business in New Orleans, working as a partner in a carriage and hardware operation. When that failed, he moved to Lawrence County, Alabama, where his wife had a home known as Pond Spring. There, with her family’s help, he became a lawyer and planter. Wheeler struggled through the Reconstruction years, embracing change by investing in railroads but still holding on to tradition by becoming an active member of the so-called “Bourbons.” The Bourbon Democrats wanted economic progress but also worked for the “Redemption” of the South by ending Reconstruction and returning power to the planter class and re-establishing white supremacy. Wheeler, like many Bourbons, tried to position himself as a moderate candidate between the Republicans and the Independent Democrats who foreshadowed the later Populists and were supported by many small farmers.

Joseph Wheeler during the Spanish-American War

After the war, Wheeler married Daniella Jones Sherrod, a widow whom he had met while fighting in northern Alabama. The couple would have seven children. He tried his hand at business in New Orleans, working as a partner in a carriage and hardware operation. When that failed, he moved to Lawrence County, Alabama, where his wife had a home known as Pond Spring. There, with her family’s help, he became a lawyer and planter. Wheeler struggled through the Reconstruction years, embracing change by investing in railroads but still holding on to tradition by becoming an active member of the so-called “Bourbons.” The Bourbon Democrats wanted economic progress but also worked for the “Redemption” of the South by ending Reconstruction and returning power to the planter class and re-establishing white supremacy. Wheeler, like many Bourbons, tried to position himself as a moderate candidate between the Republicans and the Independent Democrats who foreshadowed the later Populists and were supported by many small farmers.

Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in a hotly contested race in 1880, Wheeler served most of the term only to have the results of the election overturned. His opponent, Col. William M. Lowe, a fiery leader of the Independent Democrats, took over the seat but died soon after. Wheeler returned to Congress in 1885 to replace Lowe and served there until 1900. He served as chairman of the Committee on Expenditures and spent most of his congressional career on financial matters. He sought to heal the divisions between the North and South by promoting economic policies that would rebuild and expand the southern economy. This made him a ready ally of the proponents of the so-called New South such as Henry W. Grady.

Joseph Wheeler at Camp Wheeler, 1898

In 1897, Wheeler became a crusader in pushing the United States toward war with Spain. He led a group of congressmen who wanted to intervene in Cuba, arguing that the conflict would be a struggle for liberty and promoting the viewpoint that it was America’s duty to fight for “freedom, Christianity, and civilization.” His bellicose speeches resounded with rhetorical attacks on tyranny, couching the war against Spain in terms that echoed not only the American Revolution but also the Confederate cause. Wheeler’s nationalism and motivation for war fit easily within the ideology of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. In 1898, he volunteered for military service and rejoined the U.S. Army at the outset of the Spanish-American War. Initially a major general of volunteers, he earned a regular army commission as a brigadier general. Some former U.S. and Confederate officers noted the irony of Wheeler serving in the U.S. Army. Former Confederate general James Longstreet saw Wheeler in his U.S. uniform and could not help but comment on it. Longstreet reportedly said that he wanted to predecease Wheeler so he could hear Confederate general Jubal Early curse at him for wearing the blue uniform.

Joseph Wheeler at Camp Wheeler, 1898

In 1897, Wheeler became a crusader in pushing the United States toward war with Spain. He led a group of congressmen who wanted to intervene in Cuba, arguing that the conflict would be a struggle for liberty and promoting the viewpoint that it was America’s duty to fight for “freedom, Christianity, and civilization.” His bellicose speeches resounded with rhetorical attacks on tyranny, couching the war against Spain in terms that echoed not only the American Revolution but also the Confederate cause. Wheeler’s nationalism and motivation for war fit easily within the ideology of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. In 1898, he volunteered for military service and rejoined the U.S. Army at the outset of the Spanish-American War. Initially a major general of volunteers, he earned a regular army commission as a brigadier general. Some former U.S. and Confederate officers noted the irony of Wheeler serving in the U.S. Army. Former Confederate general James Longstreet saw Wheeler in his U.S. uniform and could not help but comment on it. Longstreet reportedly said that he wanted to predecease Wheeler so he could hear Confederate general Jubal Early curse at him for wearing the blue uniform.

Although sick at the outset of the Battle for San Juan Hill in Cuba, the sound of battle proved irresistible, and Wheeler went to the front. The division he commanded included Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and his orders led to the dramatic operations that resulted in the taking of the hill. Three of his six children had joined him in the war: his oldest son served on his staff, his daughter as a nurse, and his youngest boy in the Navy. Wheeler himself fell ill while in Cuba and spent much of the conflict incapacitated.

Joseph Wheeler in the Philippines

Later, during the Philippine-American War, he served under Gen. Arthur MacArthur in the Philippines and supposedly dismounted and carried the pack of an infantryman who complained about being too tired to continue a march. Wheeler died in New York City in 1906, a symbol both of the Old South and the New South, but also of the Civil War, the Lost Cause, and Reconciliation and Reunion. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His home was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and was donated to the Alabama Historical Commission by his descendants in 1993.

Joseph Wheeler in the Philippines

Later, during the Philippine-American War, he served under Gen. Arthur MacArthur in the Philippines and supposedly dismounted and carried the pack of an infantryman who complained about being too tired to continue a march. Wheeler died in New York City in 1906, a symbol both of the Old South and the New South, but also of the Civil War, the Lost Cause, and Reconciliation and Reunion. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His home was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and was donated to the Alabama Historical Commission by his descendants in 1993.

Additional Resources

DeLeon, T. C. Joseph Wheeler, the Man, the Statesman, the Soldier Seen in Semi-Autobiographical Sketches. Kennesaw, Ga.: Continental Publishing, 1960.

DuBose, John Witherspoon. General Joseph Wheeler and the Army of Tennessee. New York: Neale Publishing, 1912.

Dyer, John P. From Shiloh to San Juan: The Life of “Fightin’ Joe” Wheeler. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1961.