Fugitive Slave Laws and Freedom Seeking

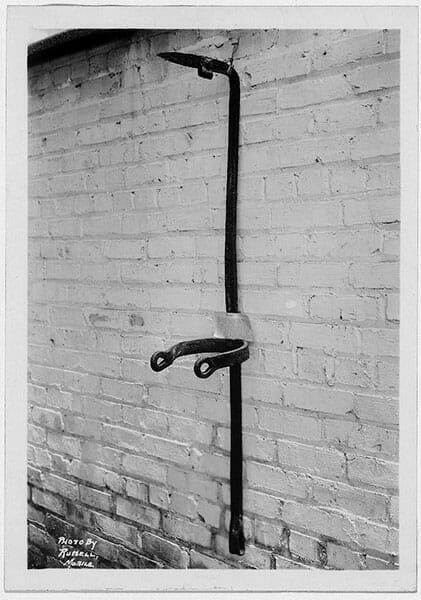

Bell Rack

As many as 435,000 enslaved people lived in Alabama in 1860, comprising about 45 percent of the state’s total population. No evidence of an organized underground railroad has been found in Alabama, forcing scholars to assume that those seeking freedom in the state relied upon their own survival skills with help from some fellow enslaved and free Blacks as well as some members of the white community.

Bell Rack

As many as 435,000 enslaved people lived in Alabama in 1860, comprising about 45 percent of the state’s total population. No evidence of an organized underground railroad has been found in Alabama, forcing scholars to assume that those seeking freedom in the state relied upon their own survival skills with help from some fellow enslaved and free Blacks as well as some members of the white community.

Historians have also encountered difficulties estimating the number of the enslaved who ran away at any given time. Many historians have typically relied on anecdotal information contained in contemporaneous newspapers in which enslavers advertised only a small fraction of the total number of escaped enslaved people, who in turn comprised a small subset of the overall enslaved population. The enslaved on most large plantations in the South, however, attempted to escape to freedom.

Resistance to slavery took many forms, such as performing careless work, destroying property, or faking illness. Many enslaved persons who were able to chose escape, however. In Alabama and throughout the rest of the South, enslaved people did so for many reasons. Some tried to rejoin family members living on a nearby properties. Others wanted to avoid the harsh working conditions in the fields during the growing season, while still others desired to escape cruel owners and brutal punishments. An overseer with a reputation for harsh punishments likely caused some enslaved people to seek freedom, if only for a few days away from the plantation. Of course, the main reason to flee was to escape the oppression of slavery itself.

To assist their flight to freedom, some escapees hid on steamboats in the hope of reaching Mobile, where they might blend in with its community of free Blacks and enslaved Blacks living on their own as though free. Others headed northward on steamboats to reach free territory and free states. The Alabama legislature, in an effort to curb this type of activity, passed an act in the Alabama Code of 1852 that penalized slave owners or masters of vessels who allowed enslaved people onboard without a pass. Canoes were also a common vehicle to freedom.

Some escapees pretended to be free people, Native Americans, or whites. Escapees possessing forged free papers ran the risk of being caught if their physical appearance did not match the description in the forged papers. In one instance, a person questioned by authorities in Greene County in 1840 claimed to be a Native American; unable to convince authorities that he was free, he was arrested. In another example, a man named London Fenderson was incarcerated as a “runaway slave” in Mobile. His status could not be settled until a Mobile city court judge found evidence that Fenderson was in fact not free. Escapees who were caught typically were whipped and sometimes shackled. Some owners sold repeat escapees.

Kidnapping of enslaved people was as much a problem for some owners as were individuals persuading enslaved people to leave their owners and go to a free state, an illegal act in Alabama. In one instance, a man kidnapped about 60 people owned by the State Bank in Tuscaloosa County and took them to Florida, where they were forced to work on a plantation. He was tracked down, however, and he and 42 of the kidnapped were returned to Alabama. In Mobile, a free man of color and an enslaved man were found guilty of enticing another enslaved man to run away. The enslaved person was sentenced to 25 lashes a day for four consecutive days, whereas the free Black man received an eight-year term of hard labor at the state penitentiary. Mobile authorities released three other persons who allegedly harbored and enticed enslaved people from their owners.

Several cases in Mobile illustrate that African Americans sometimes protected escapees from local authorities. For allegedly harboring an escaped woman, Mobile police arrested an elderly Black man who claimed he was free, but the court could not rule on the case until it determined his status. One free woman of color accused of concealing an escapee was required to pay bond. A jury convicted two free Blacks for harboring an escapee and sentenced them to two years in prison, but they were granted a new trial. In another case, a B lack woman who was legally enslaved but living as a free person was convicted of harboring an enslaved person and given the option of leaving the state or receiving 39 lashes. A free man of color accused of harboring an escapee was let go.

Whites and free people of color who harbored runaways were subject to fines ranging between $100 and $1,000, or imprisonment for two years, at the discretion of the jury. Further study is needed, however, to determine how the laws were enforced and whether the punishment differed for accused Blacks and whites. Other studies have demonstrated that not all laws against free people of color were strictly enforced throughout the state, despite the alleged threat that these individuals posed to the institution of slavery and white society.

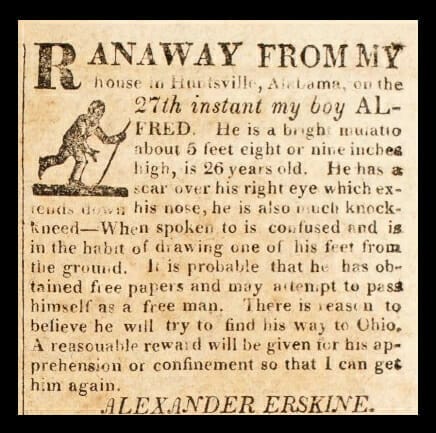

Escapee Advertisement

Descriptions of escapees posted in period newspapers reveal much about the brutal life of the enslaved. For instance, owners frequently described physical disfigurements caused by harsh punishment, such as scars from whippings, burns, or cuts. In some cases, runaways were said to be missing fingers or toes. Escapees often tried to supply themselves with items they would need during their travels to freedom. They carried clothing and often stole money from their owners. A man named Armistead took $1,100 in cash and $180 in gold when he escaped. Others carried personal items such as their musical instruments. Although it was illegal to teach enslaved people to read and write, some notices described runaways being literate, including some who could speak French or Spanish. Typically, people escaped by themselves or in small groups and hid from authorities for up to several weeks. Many often returned to their owners after suffering hunger and other hardships on their own. If escapees were captured, owners had to pay fees to free them from jail. Owners also typically offered a reward for the capture of an escapee, with the amount varying depending on the individual’s personal skills. If the person had committed a capital crime, for instance, the reward could be as high as $1,000. Escapees who were not claimed were sold at public auction.

Escapee Advertisement

Descriptions of escapees posted in period newspapers reveal much about the brutal life of the enslaved. For instance, owners frequently described physical disfigurements caused by harsh punishment, such as scars from whippings, burns, or cuts. In some cases, runaways were said to be missing fingers or toes. Escapees often tried to supply themselves with items they would need during their travels to freedom. They carried clothing and often stole money from their owners. A man named Armistead took $1,100 in cash and $180 in gold when he escaped. Others carried personal items such as their musical instruments. Although it was illegal to teach enslaved people to read and write, some notices described runaways being literate, including some who could speak French or Spanish. Typically, people escaped by themselves or in small groups and hid from authorities for up to several weeks. Many often returned to their owners after suffering hunger and other hardships on their own. If escapees were captured, owners had to pay fees to free them from jail. Owners also typically offered a reward for the capture of an escapee, with the amount varying depending on the individual’s personal skills. If the person had committed a capital crime, for instance, the reward could be as high as $1,000. Escapees who were not claimed were sold at public auction.

During the Civil War, the U.S. Army frequently occupied much of Alabama’s Tennessee Valley from the spring of 1862 on. Refugee camps were established on confiscated plantations to house thousands of people liberated by the Emancipation Proclamation and provide them with care. Beyond that, however, federal troops barely penetrated the Black Belt and other regions of the state prior to the spring of 1865. Thus, most enslaved people in Alabama were not emancipated until the war ended, unlike those in areas of the South occupied by the U.S. Army.

Further Reading

- Franklin, John Hope, and Loren Schweninger. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Kennington, Kelly. “Slavery in Alabama: A Call to Action.” Alabama Review 73(1): 3-27.

- Kolchin, Peter. First Freedom: The Response of Alabama’s Blacks to Emancipation and Reconstruction. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1972.