William Lowndes Yancey

Alabama political leader William Lowndes Yancey (1814-1863) was a preeminent figure in the secession movement that brought on the Civil War. A vehement advocate for southern rights, popularly known as a “Fire-Eater,” he accomplished his ultimate objective in 1860 when he precipitated the dissolution, not of the Union, but of the last truly national political organization: the Democratic Party. The dissolution of the Union soon followed.

William Lowndes Yancey

Yancey was born on August 10, 1814, at The Aviary, the family home of his mother, Caroline Bird Yancey, at the Shoals of Ogeechee in Georgia. His father, Benjamin Cudworth Yancey, was a leading South Carolina lawyer and legislator who died in 1817 of malaria, when William was three and his brother, B. C. Yancey Jr., was an infant. Although she removed the family to Georgia, Caroline intended that William should pursue his father’s interrupted career. She trained her son from childhood to be an orator, an important vocation for public men in the nineteenth century. For his formal education, she enrolled him in Mount Zion Academy in Hancock, Georgia. The school’s headmaster, Nathan Sidney Smith Beman, was a New England Presbyterian minister of puritanical views who had come to Georgia to recover from a mild case of tuberculosis. A widower with several grown children, Beman married Caroline Yancey in 1821. The Bemans subsequently had two children of their own, but the couple often quarreled, due to her violent temper and his extremely strict religious views.

William Lowndes Yancey

Yancey was born on August 10, 1814, at The Aviary, the family home of his mother, Caroline Bird Yancey, at the Shoals of Ogeechee in Georgia. His father, Benjamin Cudworth Yancey, was a leading South Carolina lawyer and legislator who died in 1817 of malaria, when William was three and his brother, B. C. Yancey Jr., was an infant. Although she removed the family to Georgia, Caroline intended that William should pursue his father’s interrupted career. She trained her son from childhood to be an orator, an important vocation for public men in the nineteenth century. For his formal education, she enrolled him in Mount Zion Academy in Hancock, Georgia. The school’s headmaster, Nathan Sidney Smith Beman, was a New England Presbyterian minister of puritanical views who had come to Georgia to recover from a mild case of tuberculosis. A widower with several grown children, Beman married Caroline Yancey in 1821. The Bemans subsequently had two children of their own, but the couple often quarreled, due to her violent temper and his extremely strict religious views.

In 1823, Beman accepted the pastorate of the First Presbyterian Church in Troy, New York, and brought his wife and extended family to the North. Almost nine years old at the time, William thereafter was educated at Troy Academy; the Polytechny in Chittenango, New York; Bennington Academy in Vermont; and Lenox Academy in Massachusetts, from which he graduated. He then enrolled in Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he credited Pres. Edward Dorr Griffin, a noted evangelist, for the further development of his oratorical skills. As proof of his talent, Yancey so enthusiastically endorsed presidential candidate Andrew Jackson in a college debate that local Democrats invited him to speak at a town rally, the young man’s first public political appearance.

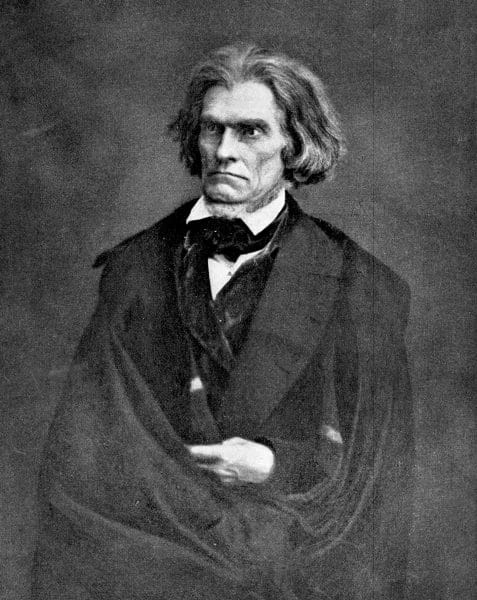

Calhoun, John C.

Despite his oratorical gifts, Yancey compiled an extensive record of misconduct in college: he was fined 16 times for disciplinary problems, including card playing, drunkenness, use of profane language, and absence from campus without permission. Furthermore, the funds his father had bequeathed for his education ran out in 1833, and the young man refused to ask his stepfather for aid. Consequently, Yancey left college his senior year without graduating. He then returned to the South to study law, finally settling in Greenville, South Carolina, where he and his law teacher, Benjamin Franklin Perry, became stalwart Unionists in the South Carolina nullification controversy of 1832. Influenced by former vice president John C. Calhoun, a native South Carolinian, the state had defied Pres. Andrew Jackson and declared null and void a federally imposed protective tariff on imported goods. The tariff greatly hampered cotton states that traded heavily with textile manufacturers in Great Britain. In public speeches, Yancey vehemently attacked Calhoun, a position he would regret in later life when he became Calhoun’s political ally. During this period, Yancey also edited a Unionist newspaper, the Greenville Mountaineer, for a short time.

Calhoun, John C.

Despite his oratorical gifts, Yancey compiled an extensive record of misconduct in college: he was fined 16 times for disciplinary problems, including card playing, drunkenness, use of profane language, and absence from campus without permission. Furthermore, the funds his father had bequeathed for his education ran out in 1833, and the young man refused to ask his stepfather for aid. Consequently, Yancey left college his senior year without graduating. He then returned to the South to study law, finally settling in Greenville, South Carolina, where he and his law teacher, Benjamin Franklin Perry, became stalwart Unionists in the South Carolina nullification controversy of 1832. Influenced by former vice president John C. Calhoun, a native South Carolinian, the state had defied Pres. Andrew Jackson and declared null and void a federally imposed protective tariff on imported goods. The tariff greatly hampered cotton states that traded heavily with textile manufacturers in Great Britain. In public speeches, Yancey vehemently attacked Calhoun, a position he would regret in later life when he became Calhoun’s political ally. During this period, Yancey also edited a Unionist newspaper, the Greenville Mountaineer, for a short time.

Yancey suspended his law studies in 1835 and married Sarah Caroline Earle, a Greenville heiress whose dowry included 35 slaves. Suddenly elevated to the planter class, Yancey became caught up in “Alabama Fever,” a land rush of the mid-1830s. Yancey sent his slaves to Cahaba, the former state capital located in the Black Belt, to join the work force and farm on the lands of his uncle, Jesse Beene, a prominent planter and state’s rights political leader. Yancey also persuaded his reluctant bride to move to Alabama in 1837. The couple lived with his uncle.

A series of calamities reduced Yancey from affluence to poverty. Prior to his departure from South Carolina, Yancey shot and killed his wife’s uncle in a street brawl after a family dispute. Tried for first degree murder in Greenville, Yancey was convicted of manslaughter, sentenced to a year in prison, and fined $1,500. Governor Patrick Noble, a family friend, pardoned Yancey after three months in jail and returned $1,000 of the fine. To add to Yancey’s troubles, the nation was plunged into the financial crisis known as the Panic of 1837, which severely depressed agriculture prices.

In 1839, while Yancey was on vacation, his overseer at Cahaba quarreled violently with a neighboring overseer who sought sexual favors from an enslaved woman on Yancey’s plantation. Seeking revenge, the neighboring overseer poisoned the spring at Yancey’s farm. The intended victim avoided the spring, but Yancey’s slaves drank the poisoned water. Two died and the others were disabled for some time. Without a significant labor force, Yancey lost his earnings from agriculture. His only source of income was an unprofitable newspaper, the Cahawba Democrat.

During this time, the turbulent marriage between Yancey’s mother and Nathan Beman ended. The two had quarreled angrily for years about domestic matters, including Caroline’s treatment of her step-children and Beman’s handling of the Yancey boys, whom he often whipped. In the late 1830s, however, slavery became entangled in the couple’s disputes, as Beman advanced from a sentimental opposition to slavery to a strong call for its abolition everywhere.

To Yancey, Beman personified the abolitionist, a hypocrite who preached against slavery after selling slaves himself, who complained about whipping slaves but lashed his stepsons, and who rejected his wife, denied her access to her own children, shut her from his house, and divided their mutual possessions without her presence or consent. The South reacted strongly to the abolitionist attack but William Yancey reacted far more strongly than most southerners because he was spurred by his intense resentment of his stepfather.

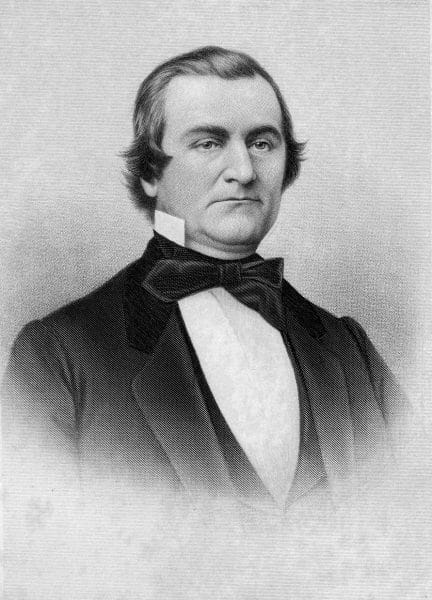

William Lowndes Yancey Portrait

By 1840, Yancey had moved to Wetumpka and become a stronger advocate of southern rights. His finances remained in disarray and were not helped by his purchase of another newspaper, the Wetumpka Argus. In the meantime, however, he began a career in politics. For a man of such far-reaching political influence, Yancey occupied public office for only a short time. He served one term only in both Alabama’s lower house (1841) and its upper house (1843). In the interim he finally passed the bar exam and began the practice of law. In the legislature, he advocated unsuccessfully for two progressive measures: apportionment that counted white voters only, the so-called “white-basis,” thus lessening the political power of the slaveholding class; and, the right of married women to hold property independently of their husbands.

William Lowndes Yancey Portrait

By 1840, Yancey had moved to Wetumpka and become a stronger advocate of southern rights. His finances remained in disarray and were not helped by his purchase of another newspaper, the Wetumpka Argus. In the meantime, however, he began a career in politics. For a man of such far-reaching political influence, Yancey occupied public office for only a short time. He served one term only in both Alabama’s lower house (1841) and its upper house (1843). In the interim he finally passed the bar exam and began the practice of law. In the legislature, he advocated unsuccessfully for two progressive measures: apportionment that counted white voters only, the so-called “white-basis,” thus lessening the political power of the slaveholding class; and, the right of married women to hold property independently of their husbands.

In 1844, Yancey was elected to the U.S. Congress, where he served two terms. He began his service with a sensational speech that advocated the annexation of Texas and specifically attacked Thomas Clingman, a North Carolina congressman who opposed annexation. When Clingman challenged Yancey to a duel with pistols, it created a hue and cry in the press, but it turned out to be a farce. Both men shot to miss. The incident established Yancey’s reputation as a celebrity rather than a statesman. He favored the expansion of slavery to Texas and opposed the complete annexation of the Oregon Territory which western Democrats favored. He also opposed internal improvements (federally financed roads, bridges, and canals) for the West, which exacerbated ill-feelings between southern and western Democrats.

After leaving Congress in September 1846, Yancey moved to Montgomery, the new capital of Alabama, where he formed a profitable law partnership with a distinguished lawyer, Albert Elmore. Yancey also participated actively in state politics. Following John C. Calhoun’s lead, the slave states had objected to the Wilmot Proviso, legislation that excluded slavery from any newly acquired U.S. territories, but Yancey led the way to an even more extreme position. At a late-night session of the state’s Democrats he convinced the drowsy delegates to adopt the Alabama Platform, which forbade the party to support any presidential candidate who favored the Wilmot Proviso or popular sovereignty, the doctrine that slavery should be decided by the territorial legislature without interference by Congress. Most extreme of all, the Alabama Platform argued that the federal government should make sure, by treaty, that Mexican antislavery law did not apply to any territory acquired as a result of the Mexican War. When many of the delegates awoke the next morning, they were dismayed at what they had passed.

Nonetheless, Yancey carried the platform to the 1848 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore, where it was rejected. It would have forbidden the Democrats to support the presidential nominee of their party, Lewis Cass, who had first proposed popular sovereignty. Yancey took a loud and flamboyant part in the convention, but with the rejection of his platform he withdrew from the convention and from the party. Only one other delegate followed him from the hall. Thus began Yancey’s six years of exile from the national Democratic Party. During the crisis over the passage of the Compromise of 1850, he took an active part in organizing the Southern Rights Party in Alabama and in advocating secession, but his efforts came to naught. He did, however, earn the sobriquet “Fire-Eater,” which was a term used to describe an opponent of any compromise on southern rights. In 1856, however, he was reunited with the Democratic Party when its national convention adopted a vague platform on territorial slavery that could be interpreted one way in the slave states and differently in the free states. To add to the confusion, the nominee of the party, James Buchanan, endorsed both sides of the issue during the campaign.

Even more importantly, shortly after Buchanan’s inauguration as president, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its bitterly contested 1857 Dred Scott decision, which essentially adopted Yancey’s view that neither Congress nor a territorial legislature could abolish slavery in a territory. Nonetheless, the new Republican Party refused to accept the decision and insisted upon the Wilmot Proviso for all the territories. Meanwhile, Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas, representing the Northern Democrats, attempted to get around the Dred Scott decision by his Freeport Doctrine, which argued that slavery could not exist in a territory without police regulations to protect it. According to Douglas, the people of a territory could abolish slavery by refusing to protect it.

In 1860, Yancey convinced the Alabama legislature to pass a resolution that the governor should call a secession convention if Lincoln were elected. In addition, Yancey persuaded the state’s Democrats once more to pass the Alabama Platform, which he introduced into the Democratic National Convention meeting in Charleston, South Carolina. After a long and furious debate the platform was rejected. Yancey and the Alabama delegation and the delegates from six other slave states walked out of the convention and left the Democratic Party divided and in ruins, ensuring Abraham Lincoln’s election. Moreover, Yancey already had made certain that Alabama would call a secession convention if Lincoln were elected.

With the election of Lincoln, Yancey successfully introduced into the Alabama state convention the resolution for secession. Probably because of his ill-tempered remarks to his opponents in that body, however, he was not chosen to represent Alabama in the provisional congress that organized the Confederate states. Nonetheless, Confederate president Jefferson Davis chose him as head of a three-man diplomatic mission to England and France to seek foreign recognition in 1861. The mission failed, and Yancey returned to Alabama in 1862 to spend his last years as senator in the Confederate Congress, where he often was at odds with the Davis administration. In the mid-1850s, he had developed Bright’s Disease, misdiagnosed as neuralgia of the spine, and he died of kidney failure at his country home outside Montgomery on July 27, 1863, soon after news of Confederate defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg dimmed southern hopes for independence. He was buried in Montgomery’s Oakwood Cemetery.

Further Reading

- Draughon, Ralph Brown, Jr. “From Unionist to Secessionist 1814-1852.” Ph.D diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1968.

- Freehling, William W. The Road to Disunion. Vol. 2: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- DuBose, John Witherspoon. The Life and Times of William Lowndes Yancey. 1892. Reprint: Whitefish, Mt.: Kessinger Publishing, 2004.

- Peterson, Owen. A Divine Discontent: The Life of Nathan S. S. Beman. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1986.

- Walther, Eric. William Lowndes Yancey and the Coming of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.