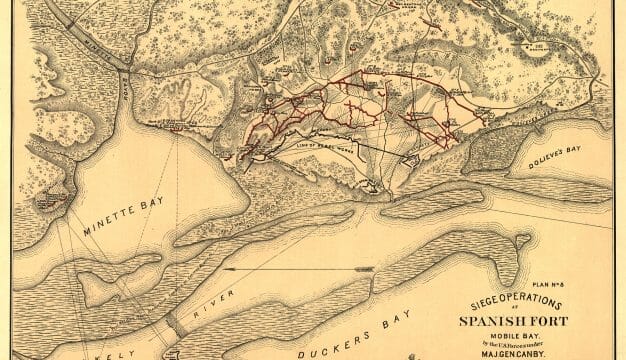

African American Union Troops

Charles Tyree

When the Civil War started, African Americans could not join the U.S. Army until Pres. Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862. By war’s end, 178,000 African Americans had enlisted and served in 170 regiments. There were six distinct African American regiments raised in Alabama along with several other regiments of mixed race and origin between 1864 and 1866, fielding nearly 7,300 soldiers in the Union Army. Historians have not definitively defined an “Alabama” regiment, and whether the partly white First Alabama Cavalry Regiment counts as “African American.” Most Blacks recruited for these regiments were formerly enslaved men who came from northern Alabama, although some came from Tennessee.

Charles Tyree

When the Civil War started, African Americans could not join the U.S. Army until Pres. Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862. By war’s end, 178,000 African Americans had enlisted and served in 170 regiments. There were six distinct African American regiments raised in Alabama along with several other regiments of mixed race and origin between 1864 and 1866, fielding nearly 7,300 soldiers in the Union Army. Historians have not definitively defined an “Alabama” regiment, and whether the partly white First Alabama Cavalry Regiment counts as “African American.” Most Blacks recruited for these regiments were formerly enslaved men who came from northern Alabama, although some came from Tennessee.

The Civil War was initially viewed as a “white man’s war” because the South had declared independence under the banner of states’ rights, and the North fought to preserve the United States. That slavery was the only state right capable of dissolving the Union was ignored by both sides. As a result, the U.S. Army, all white prior to the Civil War, remained segregated in the war’s early years. By the summer of 1862, with Union casualties mounting dramatically, white soldiers were more willing to allow Black participation. As of that fall, regiments of African Americans were formed in Kansas, the Carolinas, and Louisiana. After the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863, all African Americans could enlist.

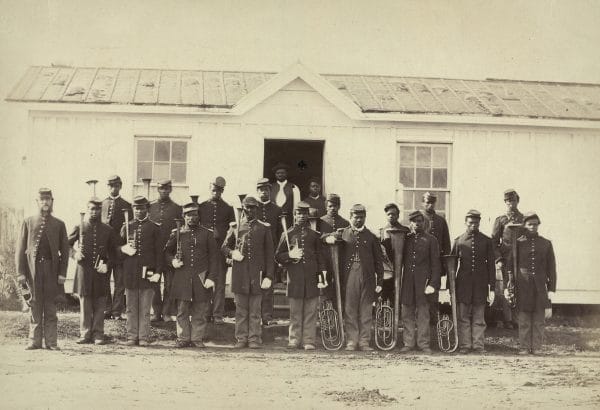

107th U.S. Colored Infantry Group Band

African American soldiers in the Union Army were put into separate regiments, called Corps d’Afrique, or African Descent, regiments. The term “colored” soon replaced that term and became universal when the army federalized the regiments into the United States Colored Troops (USCT). These regiments were commanded by white officers who were combat veterans chosen for their military competence. USCT regiments had excellent leadership, especially compared with white regiments in which commissions were often awarded on the basis of political influence, rather than military experience.

107th U.S. Colored Infantry Group Band

African American soldiers in the Union Army were put into separate regiments, called Corps d’Afrique, or African Descent, regiments. The term “colored” soon replaced that term and became universal when the army federalized the regiments into the United States Colored Troops (USCT). These regiments were commanded by white officers who were combat veterans chosen for their military competence. USCT regiments had excellent leadership, especially compared with white regiments in which commissions were often awarded on the basis of political influence, rather than military experience.

Approximately three-quarters of the blacks who joined were enslaved, either those who escaped from bondage in the South or were enslaved in border states and volunteered to serve in exchange for their freedom. (Their owners had to let them join and were paid $100 in compensation.) The actual percentage of the enslaved was likely higher, as “freedmen” who joined received more pay than enslaved men, mainly through recruiting bonuses. Many officers also were willing to take a Black man’s word that he was a freedman, even though he was likely to have escaped slavery. Given that, and that Alabama was the “Heart of Dixie,” it is doubtful that many of the Black men who joined Alabama regiments were freedmen.

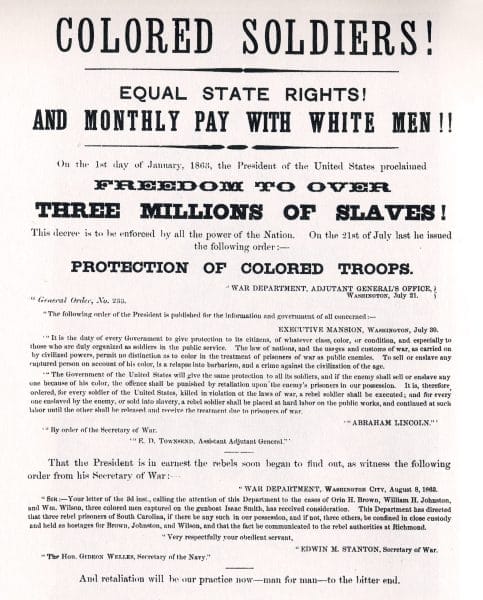

United States Colored Troops Recruitment Poster

The Union Army raised six Alabama state regiments, five of which were staffed primarily with formerly enslaved recruits. These five African American regiments initially were known as the First Alabama Siege Artillery Regiment (African Descent) and the First through Fourth Alabama Infantry Regiments (African Descent). In 1864 and 1865, these regiments were renamed. The First Alabama Siege Artillery regiment became respectively, the Sixth U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment, then the Seventh U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment, before finally being reorganized as the Eleventh United States Colored Infantry (USCI) in January 1865. When the “state” African American regiments were federalized in 1864, the First Alabama Infantry (African Descent) became the Fifty-fifth USCI, and the Second, Third, and Fourth Alabama Infantry (African Descent) became, respectively, the 110th USCI, the 111th USCI, and the 106th USCI. Another African American regiment was raised in Alabama after federalization. This was the 137th USCI, raised in Selma in 1865. These six regiments listed 7,296 men on their muster rolls over the course of their existence. The final “Alabama” regiment raised by the Union Army, the First Volunteer Alabama Cavalry, is not listed as a “Colored” regiment because it included units made up of white Alabamians loyal to the Union. Many of the 2,818 men listed on its rolls, however, were African American. Additionally, two other United States Colored Troop regiments, the Twelfth and 101st USCI (with a total of 2,791 men on their rolls), although not technically Alabama regiments, recruited heavily in Alabama and saw service in the state during the war.

United States Colored Troops Recruitment Poster

The Union Army raised six Alabama state regiments, five of which were staffed primarily with formerly enslaved recruits. These five African American regiments initially were known as the First Alabama Siege Artillery Regiment (African Descent) and the First through Fourth Alabama Infantry Regiments (African Descent). In 1864 and 1865, these regiments were renamed. The First Alabama Siege Artillery regiment became respectively, the Sixth U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment, then the Seventh U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment, before finally being reorganized as the Eleventh United States Colored Infantry (USCI) in January 1865. When the “state” African American regiments were federalized in 1864, the First Alabama Infantry (African Descent) became the Fifty-fifth USCI, and the Second, Third, and Fourth Alabama Infantry (African Descent) became, respectively, the 110th USCI, the 111th USCI, and the 106th USCI. Another African American regiment was raised in Alabama after federalization. This was the 137th USCI, raised in Selma in 1865. These six regiments listed 7,296 men on their muster rolls over the course of their existence. The final “Alabama” regiment raised by the Union Army, the First Volunteer Alabama Cavalry, is not listed as a “Colored” regiment because it included units made up of white Alabamians loyal to the Union. Many of the 2,818 men listed on its rolls, however, were African American. Additionally, two other United States Colored Troop regiments, the Twelfth and 101st USCI (with a total of 2,791 men on their rolls), although not technically Alabama regiments, recruited heavily in Alabama and saw service in the state during the war.

African American troops in Alabama and other regiments were issued the same uniforms, weapons, and rations as whites. Although African American troops believed this indicated their acceptance as equals, in reality it was cheaper to provide them standard equipment than to issue separate uniforms. Raised late in the war, the African American regiments were outfitted with new Lee-Enfield or 1861 Springfield rifles, whereas artillery units received Prussian rifles, much the same as white regiments.

African American soldiers were paid less than whites throughout most of the war. In July 1862, Congress set the pay for African American laborers working for the army equal to that of white laborers, intending to protect enslaved men who had escaped from exploitation. When the army enlisted African Americans, however, antiwar politicians forced the army to pay them at the lower laborer rate and blocked efforts to adjust for the difference. Equal pay was authorized, however, after the 1864 election swept the peace faction out of Congress.

Crew Aboard the USS Miami

Most African American regiments guarded supply lines, served as prison guards, and hunted Confederate guerillas. These were vital though unglamorous military duties required to keep the fighting armies in the field. Railroad guards protected bridges and railroad tunnels and rode aboard supply trains to protect them from raiders. Garrison troops protected towns, forts, and supply posts. Prison guards prevented captured Confederates from rejoining the war. Whereas African American regiments tended to get more than their share of “fatigue” duties, such as digging trenches and graves and cleaning latrines, they were not exclusively, nor even mostly, confined to these kinds of menial chores and drudge work. Blacks who were employed in these jobs were generally laborers hired by the Army. Only one-third of the regiments were assigned to field armies, but some of these troops played major roles at the Siege of Petersburg and the Battle of Nashville.

Crew Aboard the USS Miami

Most African American regiments guarded supply lines, served as prison guards, and hunted Confederate guerillas. These were vital though unglamorous military duties required to keep the fighting armies in the field. Railroad guards protected bridges and railroad tunnels and rode aboard supply trains to protect them from raiders. Garrison troops protected towns, forts, and supply posts. Prison guards prevented captured Confederates from rejoining the war. Whereas African American regiments tended to get more than their share of “fatigue” duties, such as digging trenches and graves and cleaning latrines, they were not exclusively, nor even mostly, confined to these kinds of menial chores and drudge work. Blacks who were employed in these jobs were generally laborers hired by the Army. Only one-third of the regiments were assigned to field armies, but some of these troops played major roles at the Siege of Petersburg and the Battle of Nashville.

Overall, African American soldiers exceeded the expectations of their white commanders. In 1863, poorly trained African American troops repulsed a Confederate assault at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana. Colored regiments stormed bastions at Port Gibson, Louisiana, and Fort Wagner, South Carolina; and the First Kansas Infantry (Colored) was the key to a decisive Union victory at Honey Springs, in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). One Union officer later observed that he could not recall an instance in which an African American regiment was routed off the field in a panic as had white brigades or even divisions.

African American Union Troops

None of the Alabama units fought in these battles. Four companies of the First Alabama Siege Artillery regiment (then designated the Sixth USCHA) were present at the Fort Pillow Massacre in Tennessee and suffered heavily. Alabama troops in the 106th, 110th, and 111th USCI Regiments also engaged Nathan Bedford Forrest at Athens, Limestone County, on September 23-24, 1864. They fought courageously, the 111th USCI losing most of its numbers in the battle. Forrest convinced the Union commander to surrender by inflating the number of troops he claimed to have during a parley, but no Blacks were massacred as at Fort Pillow. In large measure, however, the African American Alabama regiments guarded railroad lines in Tennessee and Alabama and performed occupation duties after the Confederate surrender.

African American Union Troops

None of the Alabama units fought in these battles. Four companies of the First Alabama Siege Artillery regiment (then designated the Sixth USCHA) were present at the Fort Pillow Massacre in Tennessee and suffered heavily. Alabama troops in the 106th, 110th, and 111th USCI Regiments also engaged Nathan Bedford Forrest at Athens, Limestone County, on September 23-24, 1864. They fought courageously, the 111th USCI losing most of its numbers in the battle. Forrest convinced the Union commander to surrender by inflating the number of troops he claimed to have during a parley, but no Blacks were massacred as at Fort Pillow. In large measure, however, the African American Alabama regiments guarded railroad lines in Tennessee and Alabama and performed occupation duties after the Confederate surrender.

Whereas the nineteenth century was a difficult one for all Black men, those who served in the Union Army during the war generally fared better later in life than those who had remained civilians. They still faced the racism of a society that refused to allow them citizenship before the war and treated them at best as second-class citizens during the war. However, the training they had undergone and their leadership experiences provided them with skills they used after the war and proved to white officers that they could assume the responsibilities of citizenship. Additionally, they were able to collect pensions when they grew old.

Regardless, it took courage to join the Army rather than simply to work as a laborer. Confederate soldiers treated African American soldiers and their white officers with extreme harshness. The chances of a soldier or officer in an African American being taken prisoner were low as many were killed outright. Even white Union troops treated them shabbily, though attitudes typically changed after a white regiment fought alongside an African American regiment. At the war’s end, African American veterans were sent home with their uniforms, weapons, and ammunition. They had won a rough legal equality for African Americans in the South, which they kept until the end of Reconstruction.

Further Reading

- Cornish, Dudley Taylor. The Sable Arm: Negro Troops in the Union Army, 1861-1865. New York: Longmans, Green, 1956.

- Davis, Robert S. “Fighting for Freedom.” Alabama Heritage 135 (Winter 2020): 16-27.

- Gladstone, William A. United States Colored Troops, 1863-1867. Gettysburg, Pa.: Thomas Publications, 1990.

- Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. Army Life in a Black Regiment. Boston: Fields, Osgood & Co., 1870.

- Lardas, Mark and Peter Dennis. African-American Soldier in the Civil War (USCT) 1862-1866. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing, 2006.

- Raines, Howell. Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta—And Then Got Written Out of History. New York: Crown, 2023.

- Taylor, Susie King. Reminiscences of My Life in Camp: A Black Woman’s Civil War Memoirs. Boston: Published by the Author, 1902.

- Wilson, Joseph T. The Black Phalanx. Hartford, Conn.: American Publishing Company, 1890.