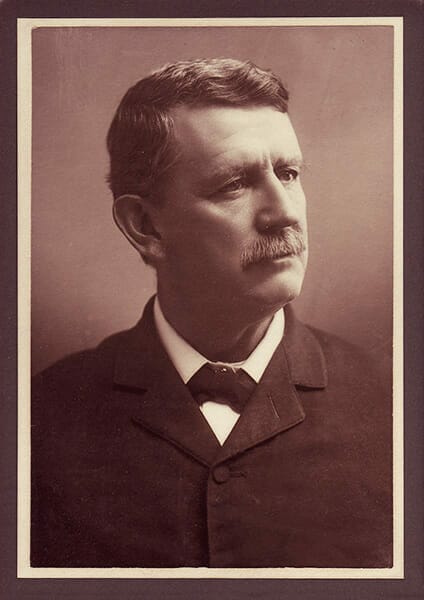

William J. Samford (1900-01)

William James Samford (1844-1901) died only six months after assuming office as the 32nd governor of Alabama. Samford was a lawyer and politician who rose rapidly in Alabama politics during the turbulent and complex post–Civil War era, but his short tenure in the office left him little chance to make a mark on the state.

William J. Samford

Samford was born on September 16, 1844, in Greenville, Georgia, to William Flewellyn Samford and Susan Lewis Dowdell Samford. His father was a professor of English literature at Emory College (now Emory University) in Georgia before he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1840. He moved his family to Chambers County, Alabama, in 1846 and became a planter and then editor of several Alabama newspapers. The elder Samford lost the Democratic gubernatorial nomination to Andrew B. Moore in 1857 and ran again, unsuccessfully, as an independent in 1859, charging Moore with negligence in defending the principle of states’ rights, typically code for support of slavery. Known as the “penman of the Civil War in Alabama,” Samford was an ardent secessionist who continued to write extensively on the political issues of the day throughout his life. Young William was shaped by his father’s ardent support of states’ rights and his interest in literature, law, writing, and oratory and by his mother’s elite upbringing and religiosity.

William J. Samford

Samford was born on September 16, 1844, in Greenville, Georgia, to William Flewellyn Samford and Susan Lewis Dowdell Samford. His father was a professor of English literature at Emory College (now Emory University) in Georgia before he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1840. He moved his family to Chambers County, Alabama, in 1846 and became a planter and then editor of several Alabama newspapers. The elder Samford lost the Democratic gubernatorial nomination to Andrew B. Moore in 1857 and ran again, unsuccessfully, as an independent in 1859, charging Moore with negligence in defending the principle of states’ rights, typically code for support of slavery. Known as the “penman of the Civil War in Alabama,” Samford was an ardent secessionist who continued to write extensively on the political issues of the day throughout his life. Young William was shaped by his father’s ardent support of states’ rights and his interest in literature, law, writing, and oratory and by his mother’s elite upbringing and religiosity.

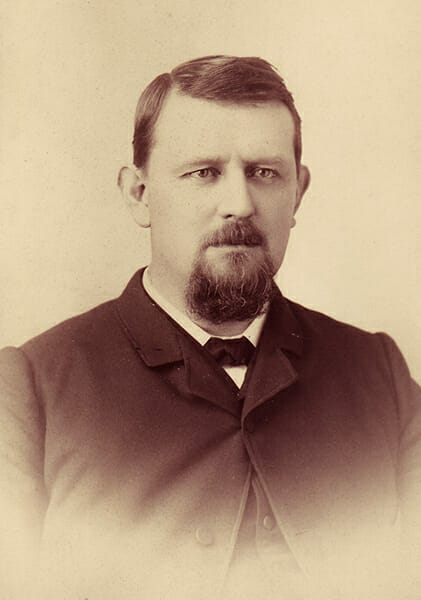

William Samford began his education at age seven at the Classical School in Oak Bowery in Chambers County and continued in the public schools of Tuskegee and Auburn. He worked after school as a typesetter at his father’s Tuskegee newspaper. Samford attended the East Alabama Male College (now Auburn University) and then transferred to the University of Georgia, but his education was cut short by the Civil War. In May 1862, the 17-year-old Samford enrolled as a private in the Forty-sixth Alabama Regiment and rose through the ranks to become first lieutenant of G Company. Captured in May 1863 at the battle of Baker’s Creek, he was incarcerated at Johnson’s Island on Lake Erie, where he encountered his old schoolmaster from Oak Bowery, Maj. William F. Slaton. During his 18-month confinement, he resumed his studies in classics and mathematics. Released in a large prisoner exchange in January 1865, he rejoined his regiment and, at war’s end, returned to his Auburn home a Confederate hero.

William J. Samford

Despite parental warnings about their reduced circumstances in the aftermath of the war, he married Caroline Elizabeth Drake of Auburn in October 1865. They moved to a farm near Auburn and eventually had nine children. Samford worked his farm by day and read law in the evenings, earning admission to the Alabama State Bar in 1867. He opened a practice in nearby Opelika in 1870, but his meager earnings of $200 in the first year forced a return to farming for another season. He reopened his office in 1872 and moved his family to Opelika, where they endured austere conditions as he established his reputation as an attorney and orator. A devout Christian, Samford was a licensed preacher in the Methodist Episcopal Church South and served regularly as a delegate to the Alabama annual conference.

William J. Samford

Despite parental warnings about their reduced circumstances in the aftermath of the war, he married Caroline Elizabeth Drake of Auburn in October 1865. They moved to a farm near Auburn and eventually had nine children. Samford worked his farm by day and read law in the evenings, earning admission to the Alabama State Bar in 1867. He opened a practice in nearby Opelika in 1870, but his meager earnings of $200 in the first year forced a return to farming for another season. He reopened his office in 1872 and moved his family to Opelika, where they endured austere conditions as he established his reputation as an attorney and orator. A devout Christian, Samford was a licensed preacher in the Methodist Episcopal Church South and served regularly as a delegate to the Alabama annual conference.

In 1872, Samford began his political career as an Opelika city alderman. Moving swiftly into state politics, in the same year he served as a delegate to the state Democratic Party convention and as an alternate elector on the Horace Greeley ticket. Although he thought the selection of Greeley was a mistake, he supported the party, a pattern of compromise that marked Samford’s political career. As a member of the Lee County Executive Committee of the Democratic and Conservative Party, Samford used his oratorical talents on the stump to win the Third District for gubernatorial candidate George S. Houston in 1874. With conservative Democrats in control, he supported the call for a constitutional convention and, at age 30, was elected the youngest delegate of the convention. Serving on the Finance Committee, he was instrumental in limiting the taxing power of the state legislature in the 1875 constitution.

In 1878, Samford won the nomination of his party to the U.S. Congress from the Third District. In his single term as a congressman, he held conservative positions on states’ rights and centralized power, but his agrarian background led him to support unlimited coinage of silver (which would make currency more broadly available to the average citizen), a position later taken by reform-minded Populists. He also supported the unsuccessful Reagan bill, which would have given the federal government the power to regulate railroads. Missing his family, he declined to run for reelection and returned to Opelika.

Auburn University

After resuming his law practice, Samford again plunged into state politics, earning a reputation as one of the state’s finest orators. Elected to represent Lee County in the Alabama House of Representatives in 1882, Samford moved to the state Senate for terms in 1884-88 and 1892-96, serving two years as president of that body. Reflecting his growing statewide reputation, in 1896 he was appointed a trustee of the University of Alabama. In 1899, Samford finally reached the top rung of state politics, winning the Democratic nomination for governor on the third ballot.

Auburn University

After resuming his law practice, Samford again plunged into state politics, earning a reputation as one of the state’s finest orators. Elected to represent Lee County in the Alabama House of Representatives in 1882, Samford moved to the state Senate for terms in 1884-88 and 1892-96, serving two years as president of that body. Reflecting his growing statewide reputation, in 1896 he was appointed a trustee of the University of Alabama. In 1899, Samford finally reached the top rung of state politics, winning the Democratic nomination for governor on the third ballot.

Samford’s rise in state politics occurred during tumultuous years in Alabama. After Reconstruction ended, conservative “Bourbons” and the Democratic Party controlled state politics through the party caucus and by intimidation and manipulation of the votes of blacks in the Black Belt counties. In the 1880s and 1890s, Greenbackers and Populists, mainly from the hill counties of north Alabama, denounced the political alliance between Black Belt planters and urban industrialists but with little lasting success. Samford’s immediate predecessor, Joseph F. Johnston, won the gubernatorial election as a reformer and succeeded in bringing many Populists back into the Democratic Party. The state’s more conservative Democrats distrusted Johnston and were angry at him for refusing to call a convention to write a new constitution that would disfranchise black voters. They pushed for a candidate who would support such a convention and succeeded in returning the governorship to a Bourbon when they nominated Samford as the Democratic candidate for governor in 1900.

Samford endorsed the party platform, which called for suffrage changes if white voters were not disenfranchised. He easily won the governorship in the general election over token opposition from Republicans and Populists. During the campaign, Samford’s fragile health from a degenerative heart condition became increasingly apparent. The legislature met in November to organize itself and elect a president of the Senate who could take over as governor should Samford die. They also approved a bill for a popular vote on calling a constitutional convention, pledging that the constitution would be submitted to voters for ratification.

As the time neared for his inauguration, Samford was too ill to travel to Montgomery for that event. Sworn in while on his sickbed by his son, Samford asked the recently elected president of the Senate, William Dorsey Jelks, to serve as acting governor until he recuperated. During Jelks’s December tenure, he approved Samford’s appointments to the railroad commission, and both he and Samford expressed concerns over legislative spending that put the state increasingly in debt. Samford finally took office on December 26, 1900, and personally decried the debt. Urging fiscal restraint, Samford recommended that state railroad commissioners also serve as the state’s Board of Pardons at no additional pay.

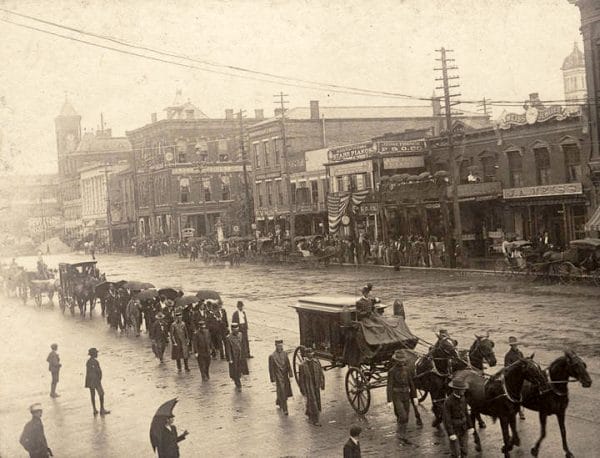

William J. Samford Funeral Procession

In April 1901, 155 delegates to a constitutional convention were elected on the same apportionment as the state legislature, assuring control of the convention by the Black Belt and south Alabama. The delegates convened in Montgomery on May 23, 1901, but Samford died on June 11, less than a month later, after attending a University of Alabama trustees’ meeting in Tuscaloosa. He was buried in Rosemere Cemetery in Opelika. In addition to endorsing the call for a constitutional convention, the only other substantive accomplishment of his short days in office was the creation of the Alabama Department of Archives and History to house the public records and artifacts of the state. On Samford’s death, Jelks assumed the governorship and the responsibility of implementing the new constitution that was ratified on November 11, 1901—again with fraudulent votes from Alabama’s Black Belt region. The provisions of the new constitution not only effectively eliminated the votes of black Alabamians but also diminished the vote of poor whites in future years.

William J. Samford Funeral Procession

In April 1901, 155 delegates to a constitutional convention were elected on the same apportionment as the state legislature, assuring control of the convention by the Black Belt and south Alabama. The delegates convened in Montgomery on May 23, 1901, but Samford died on June 11, less than a month later, after attending a University of Alabama trustees’ meeting in Tuscaloosa. He was buried in Rosemere Cemetery in Opelika. In addition to endorsing the call for a constitutional convention, the only other substantive accomplishment of his short days in office was the creation of the Alabama Department of Archives and History to house the public records and artifacts of the state. On Samford’s death, Jelks assumed the governorship and the responsibility of implementing the new constitution that was ratified on November 11, 1901—again with fraudulent votes from Alabama’s Black Belt region. The provisions of the new constitution not only effectively eliminated the votes of black Alabamians but also diminished the vote of poor whites in future years.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Samford, William J. Typescript biographical sketch. Samford University Special Collections, Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.

- Smith, George Hudson. “The Life and Times of William J. Samford.” Master’s thesis, Samford University, 1969.

- Sobel, Robert, and John Raimo, eds. Biographical Directory of the Governors of the United States, 1789-1978. Westport, Conn.: Meckler Books, 1978.