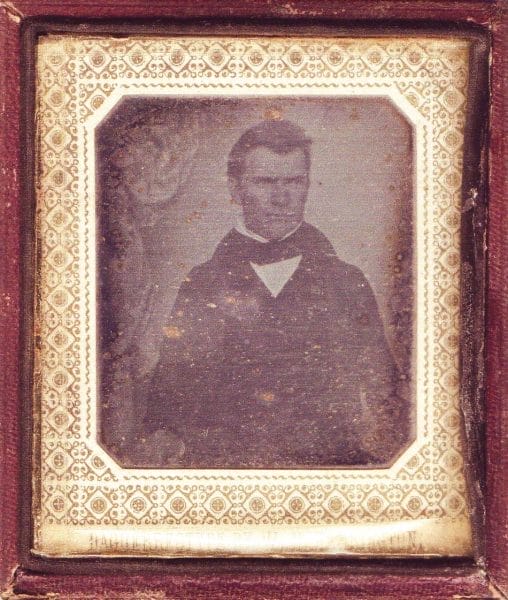

Joshua L. Martin (1845-47)

Joshua Lanier Martin (1799-1856) was the Alabama governor who delivered the final blow to the state bank. Martin’s legacy was one of dedicated public service through the Democratic Party, which ironically reached its zenith when, as an independent governor, he did what other Democrats had feared to do and dismembered the state bank.

Joshua L. Martin

Martin was a descendant of French immigrant Louis Montaigne, who changed his name to Martin, immigrated to South Carolina in 1724, and then, like the ancestors of numerous other Alabama families, made the trek to Tennessee. Joshua Martin was born on December 5, 1799, near Maryville in Blount County, Tennessee. Martin received a general education under the tutelage of two local ministers, and in 1819, at the age of 20, he moved with his family to Alabama. He married twice, first to Mary Gillam Mason and later to Sarah Ann Mason, sisters who were members of the distinguished Mason family of Virginia. He had five sons and two daughters with his wives.

Joshua L. Martin

Martin was a descendant of French immigrant Louis Montaigne, who changed his name to Martin, immigrated to South Carolina in 1724, and then, like the ancestors of numerous other Alabama families, made the trek to Tennessee. Joshua Martin was born on December 5, 1799, near Maryville in Blount County, Tennessee. Martin received a general education under the tutelage of two local ministers, and in 1819, at the age of 20, he moved with his family to Alabama. He married twice, first to Mary Gillam Mason and later to Sarah Ann Mason, sisters who were members of the distinguished Mason family of Virginia. He had five sons and two daughters with his wives.

Martin was a precocious young man who had an ingratiating personality and an aptitude for the law. He studied with his brother in Russellville, was admitted to the State Bar, and opened a law office in Athens. In 1822, Martin was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives from Limestone County, a position he held, except for one year, until 1828. In 1829, Martin was elected solicitor of the Fourth Judicial Circuit; five years later he defeated a former justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, Judge John White of Talladega, for a seat on the Circuit Court. In 1835, he was elected as one of Alabama’s five representatives to the U.S. Congress and was reelected in 1837. At the end of his second term, Martin returned to private life, and in 1841 he was elected chancellor of the Middle Chancery Division of the state.

Opposition to the State Bank

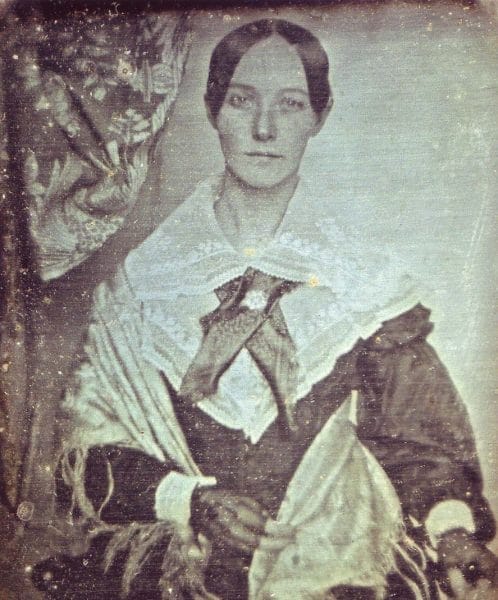

Sarah Ann Martin, 1840

Martin’s decision to run for governor was directly related to his long and consistent opposition to the state bank, which was chartered in 1823 in the wake of the Panic of 1819. For more than a decade, the bank won the almost universal approval of Alabamians, providing financing that was otherwise unavailable and in some years, through its profits, paying the state’s operating expenses and allowing the legislature to abolish direct taxes. When the depression of 1837 came, the imprudent actions of the bank and its branches led to serious consequences, however, and the bank’s charter, which expired in 1845, was not renewed. Powerful forces within both the Whig and Democratic parties were in favor of renewing the charter and saving the bank, however. In 1845, antibank delegates were delayed in arriving at the Democratic convention at Tuscaloosa because their boats could not move through the surprisingly shallow levels in the Warrior and Tombigbee Rivers. In their absence, pro-bank delegates constituted a majority and hurriedly nominated Nathaniel Terry of Limestone County, a legislator and large debtor to the bank, as the party’s candidate for governor.

Sarah Ann Martin, 1840

Martin’s decision to run for governor was directly related to his long and consistent opposition to the state bank, which was chartered in 1823 in the wake of the Panic of 1819. For more than a decade, the bank won the almost universal approval of Alabamians, providing financing that was otherwise unavailable and in some years, through its profits, paying the state’s operating expenses and allowing the legislature to abolish direct taxes. When the depression of 1837 came, the imprudent actions of the bank and its branches led to serious consequences, however, and the bank’s charter, which expired in 1845, was not renewed. Powerful forces within both the Whig and Democratic parties were in favor of renewing the charter and saving the bank, however. In 1845, antibank delegates were delayed in arriving at the Democratic convention at Tuscaloosa because their boats could not move through the surprisingly shallow levels in the Warrior and Tombigbee Rivers. In their absence, pro-bank delegates constituted a majority and hurriedly nominated Nathaniel Terry of Limestone County, a legislator and large debtor to the bank, as the party’s candidate for governor.

Martin, who was incensed by the Democratic convention’s action, acceded to the request of many who shared his views on the bank and ran as an independent candidate. Like the national campaign of 1840, the 1845 Alabama gubernatorial contest was one of the most intense the state had yet seen. The Whigs did not field a candidate and were divided in their sentiment regarding Terry’s fitness for office. Some of them supported Terry and his pro-bank position, but others opposed him because he had authored the controversial general ticket law, soon repealed, that provided for the election of the state’s congressional delegates “at large.” These factors and Martin’s intense campaigning led to his election by a 5,000-vote margin.

Term as Governor

As governor, Martin was often opposed and maligned by the “regular” Democrats, who never forgave him for his disloyalty to the party. Nevertheless, he pursued the dismantling of the bank with vigor. The legislature appointed Francis S. Lyons of Marengo County to collect as much of the debt owed to the bank as possible and to liquidate its assets and obligations. Lyons performed the mission with great ability until his retirement in 1853. Although the state lost millions of dollars, its credit was protected and economic disaster averted.

During the one-term governor’s tenure, the legislature acknowledged the growing population of the newly created counties that had emerged from former Creek Nation lands in central and east Alabama by approving removal of the capital from Tuscaloosa to the more central location at Montgomery. The amendment to the constitution that accomplished this move was ratified by a narrow margin, and in 1846 Martin and the state government moved into the capitol that was built and paid for by the city fathers of Montgomery. The operation of the poorly managed state penitentiary, which had opened in Wetumpka in 1841, was privatized in 1846. A six-year lease provided that for $500 in annual rent and the payment of operating expenses, John Graham of Coosa County had the right to all profits that could be earned from the inmates’ labor. While these events were occurring, the Mexican War enjoyed popular support in Alabama, and many of the state’s citizens volunteered for army service, although few saw actual battleground action during the brief conflict.

Although Martin would have liked a second term, he understood that he was disliked by many within the party and that his candidacy would do irreparable damage to the Democrats and almost certainly insure a Whig victory. He chose not to run for a second term, and in 1847 resumed the practice of law in Tuscaloosa. He was again elected to the state legislature in 1853 and died three years later in Tuscaloosa on November 2, 1856.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Neeley, Mary Ann. “Painful Circumstances: Glimpses of the Alabama Penitentiary, 1846-1852.” Alabama Review 44 (January 1991): 3-16.

- Stewart, John Craig. The Governors of Alabama. Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing, 1975.