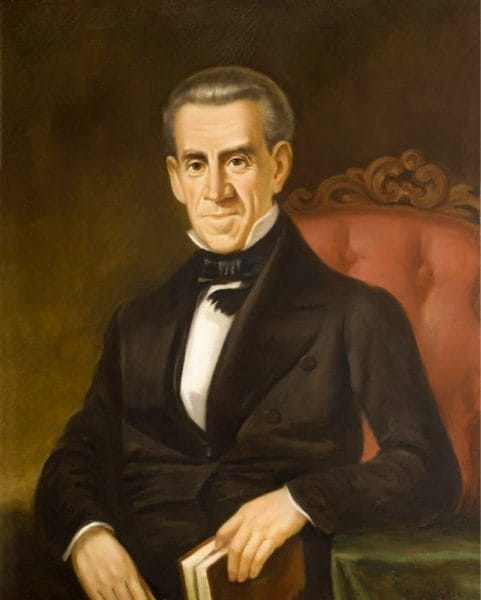

Gabriel Moore (1829-31)

An affluent attorney, plantation owner, U.S. congressman, and Alabama governor, Gabriel Moore (ca. 1785–1844) built his political career with appeals to the small farmers who populated Madison County and with attacks on the wealthy merchants and planters of Huntsville. Moore owned approximately 500 acres of land and four enslaved people in 1815, property holdings that placed him closer to the typical pioneer settler of the county than the business elite in the town. Moore, observed a contemporary, was “a skillful electioneer [who] courted the lower stratum of society.” He appealed to the common people by delivering stump speeches in which he declared that he came not from the “Royal Party” but from the poor.

Gabriel Moore

The son of Matthew and Letitia Dalton Moore, Gabriel Moore was born in what at the time was Surry County (now Stokes County), North Carolina, circa 1785. He received his education at David Caldwell’s Academy, popularly known as the “Log College,” a forerunner of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. He read law in North Carolina and in 1810 moved to Huntsville in what was then the Mississippi Territory. He immediately entered public service with his appointment in 1810 as tax assessor and collector for Madison County. His duties included supervising the county census, which helped determine the apportionment of representatives to the Mississippi Territorial Assembly.

Gabriel Moore

The son of Matthew and Letitia Dalton Moore, Gabriel Moore was born in what at the time was Surry County (now Stokes County), North Carolina, circa 1785. He received his education at David Caldwell’s Academy, popularly known as the “Log College,” a forerunner of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. He read law in North Carolina and in 1810 moved to Huntsville in what was then the Mississippi Territory. He immediately entered public service with his appointment in 1810 as tax assessor and collector for Madison County. His duties included supervising the county census, which helped determine the apportionment of representatives to the Mississippi Territorial Assembly.

Moore represented Madison County in the assembly from 1811 to 1817 and served as its speaker from 1815 to 1817, when Alabama became a separate territory. Moore continued to represent the county in the Alabama Territorial Assembly and served as speaker during its first session in January and February 1818. He did not seek election as speaker for the second session in November, fearing political repercussions after the legislature’s grant of a divorce to his wife and approval of her petition to resume her maiden name, Mary Parham Caller. Compounding the political fallout, Moore subsequently fought a duel with her brother, although neither suffered serious injury.

1819 Constitutional Convention

Moore’s reputation survived his personal difficulties, and in 1819 he was one of eight Madison County representatives to the state constitutional convention in Huntsville. Moore then handily won election as the first state senator from Madison County, receiving almost four times as many votes as his opponent and predictably drawing most of them from residents of the county rather than from Huntsville proper. He served as president of the Alabama Senate in 1820.

Clement Comer Clay, 1835

Moore served as a representative for Alabama in the U.S. Congress from 1821 to 1829. During this time, he sought surveys of possible routes to connect the Alabama and Tennessee River systems and ways to facilitate navigation on the Tennessee River. He ultimately proved successful in obtaining extensive federal aid for navigation improvements around Muscle Shoals. But he also made powerful enemies, including Clement Comer Clay, a leader of the Broad River faction of Madison County and a future governor. In 1825, Moore defeated Clay in a bid for his seat in the U.S. Congress. The following year, Moore refused to support Clay’s quest for a seat in the House of Representatives, insuring his defeat. From that time forward, Clay despised Moore, and years later, when the two men happened to ride in the same stagecoach, neither acknowledged the other’s presence for the 170 miles of the trip.

Clement Comer Clay, 1835

Moore served as a representative for Alabama in the U.S. Congress from 1821 to 1829. During this time, he sought surveys of possible routes to connect the Alabama and Tennessee River systems and ways to facilitate navigation on the Tennessee River. He ultimately proved successful in obtaining extensive federal aid for navigation improvements around Muscle Shoals. But he also made powerful enemies, including Clement Comer Clay, a leader of the Broad River faction of Madison County and a future governor. In 1825, Moore defeated Clay in a bid for his seat in the U.S. Congress. The following year, Moore refused to support Clay’s quest for a seat in the House of Representatives, insuring his defeat. From that time forward, Clay despised Moore, and years later, when the two men happened to ride in the same stagecoach, neither acknowledged the other’s presence for the 170 miles of the trip.

Race for Governor

In 1829, Moore entered the race for the governorship of Alabama, winning without opposition. He quickly gained widespread support for his long-term priorities for the state: internal improvements and land debt relief for citizens who lost money in the Panic of 1819. Moore asked the legislature to pass measures to link the Alabama and Tennessee River systems, thereby connecting north and south Alabama in the hope that farm income and real estate values would rise and trade at the state’s seaport in Mobile would increase. In 1830, as navigational improvements began at Muscle Shoals, Moore brought the Tennessee–Alabama River project to the legislature again.

Moore’s agenda also included an appeal to small farmers through calls for equitable land distribution. Thousands of acres in Alabama were opened to settlement after the Creeks and other Native American tribes were forcibly removed from their land in the early 1830s by the federal government, which intended to sell the land in large parcels and at high prices. Moore advocated making the land available to settlers in small parcels, preferably 40 acres, and at graduated prices depending on the fertility of the soil. Without these changes in land policy, the governor argued, many Alabamians would continue to migrate westward.

Education and Prison Reform

Moore also promoted education, observing that “the increase of knowledge is the best security for sound public morality.” In his 1830 address to the legislature, he spoke eloquently about the imminent opening of the University of Alabama, which would extend “the benefits of education to even the humblest of our citizens.” He also advocated penal and judicial reform and asked the legislature, without success, to establish a centralized state penitentiary system capable of rehabilitating prisoners. Moore also sought a more enlightened criminal justice system that was “founded on principles of reformation, and not of vindictive justice” and advocated the establishment of a separate state Supreme Court to replace the existing system in which state circuit judges were also called upon to serve as a supreme court. The lawmakers enacted this system on January 14, 1832, after Moore’s tenure as governor.

Moore supported the State Bank of Alabama and unsuccessfully petitioned the legislature to establish branches in the Tennessee Valley and south Alabama to provide more efficient service to those regions of the state. A dedicated Jacksonian, Moore opposed the Bank of the United States as a “mammoth institution” and urged Alabama’s congressional delegation to vote against renewal of its charter.

Eyes on the U.S. Senate

John McKinley

Almost immediately after he had won the governorship, Moore began to maneuver for a return to the U.S. Congress as a senator. His support of Pres. Andrew Jackson and stance against the Bank of the United States served him well, as did his questions about incumbent Sen. John McKinley‘s loyalty to Jackson. In 1830, Moore formally announced his candidacy for the Senate and won after a bitter campaign in which McKinley questioned Moore’s own commitment to Jackson. On March 3, 1831, he resigned the governorship.

John McKinley

Almost immediately after he had won the governorship, Moore began to maneuver for a return to the U.S. Congress as a senator. His support of Pres. Andrew Jackson and stance against the Bank of the United States served him well, as did his questions about incumbent Sen. John McKinley‘s loyalty to Jackson. In 1830, Moore formally announced his candidacy for the Senate and won after a bitter campaign in which McKinley questioned Moore’s own commitment to Jackson. On March 3, 1831, he resigned the governorship.

Moore quickly lost the popular support that had brought him to the Senate by allying himself in 1832 with Vice President John C. Calhoun in opposing confirmation of Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s nominee as American minister to Great Britain. Jackson reacted to Moore’s disloyalty by encouraging political opposition to him in Alabama. Public meetings in north Alabama in February and March 1832 called for Moore’s resignation. Despite his earlier professed beliefs in the practice of legislative instruction, when the Alabama legislature joined the public outcry and called for his resignation, Moore refused and completed his term. Aware that legislators would not give him a second term in the U.S. Senate, Moore ran in 1836 for his old seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He suffered his first election defeat, and he never again held public office.

Following his involuntary retirement from public office, Moore experienced financial setbacks that coincided with the Panic of 1837. Between 1841 and 1843, the Circuit Court of Madison County placed liens in favor of his creditors on more than 2,000 acres of land and 60 enslaved people that Moore had pledged as collateral on defaulted loans. Moore left the state with a few slaves and moved to a rented plantation in Panola County, Mississippi, in 1843, and then to the Republic of Texas in 1844. He died in Texas on August 6, 1844, and was buried near Caddo Lake in Harrison County. Moore’s will and subsequent litigation provided freedom for some of the slaves he had transported to Texas. One of the slaves with whom he travelled and who won her freedom after his death was Mary Minerva, who court records indicate was Moore’s daughter.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Carter, E. Clarence, ed. Territorial Papers of the United States. Vol. 6. The Territory of Mississippi, 1809-1817. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1938.

- Doss, Harriet E. Amos. “The Rise and Fall of an Alabama Founding Father, Gabriel Moore.” Alabama Review (July 2000): 163–76.

- Dupre, Daniel. Transforming the Cotton Frontier: Madison County, Alabama, 1800-1840. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997.

- Martin, James M. “The Early Career of Gabriel Moore.” Alabama Historical Quarterly 29 (Fall/Winter 1967): 89–105.

- ———. “The Senatorial Career of Gabriel Moore.” Alabama Historical Quarterly 26 (Summer 1964): 249–81.

- Moore, Gabriel. Papers. Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery.