Israel Pickens (1821-25)

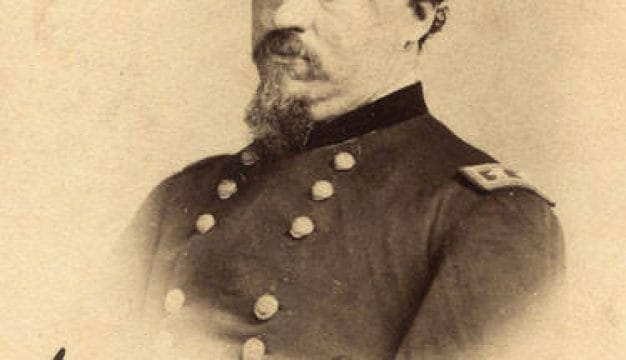

Israel Pickens

Israel Pickens (1780-1827) was an established politician who migrated to Alabama in search of greater opportunities. Having served North Carolina in the U.S. House of Representatives, Pickens moved to Alabama and successfully battled wealthy former Georgians for political and economic control of the new state, overseeing the creation of a state bank during a period when banking issues were deeply divisive. He was Alabama’s third governor.

Israel Pickens

Israel Pickens (1780-1827) was an established politician who migrated to Alabama in search of greater opportunities. Having served North Carolina in the U.S. House of Representatives, Pickens moved to Alabama and successfully battled wealthy former Georgians for political and economic control of the new state, overseeing the creation of a state bank during a period when banking issues were deeply divisive. He was Alabama’s third governor.

Born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, on January 30, 1780, Israel was the son of Capt. Samuel Pickens, a veteran of the American Revolution, and Jane Carrigan Pickens. After first attending a local academy, he studied law at Jefferson College in Pennsylvania. In 1802, Pickens moved to Burke County, in western North Carolina, to practice law and was soon caught up in politics. His election to the state senate in 1808 was a stepping stone to higher office; North Carolina voters sent Pickens to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1811, where he served until 1817. A staunch supporter of Pres. James Madison, Pickens was one of Congress’s “War Hawks,” an important group of southern and western politicians who pushed the nation toward military conflict with England in 1812.

Move to Alabama

Politics and war were not the only things on Pickens’s mind during this period; he courted and married Martha Lenoir, the daughter of one of North Carolina’s wealthiest men, in 1814. Like countless other residents of the Eastern seaboard, he was struck by Alabama land fever as cotton prices soared and new fertile lands opened in the Old Southwest in the post–War of 1812 period through Indian land cessions. He decided not to run for a fourth term in Congress and instead moved to St. Stephens, in the Mississippi Territory, in the spring of 1817 to take a job as a register of the land office for Washington County. Wasting no time in establishing himself in his new home, Pickens purchased almost 3,500 acres in southwest Alabama in less than a year and became the first president of the Tombigbee Bank of St. Stephens. Forging alliances with business elites in this burgeoning new community, he proved adept at finances and was instrumental in helping the bank maintain its reserves of gold and silver (specie) during the Panic of 1819.

Greenwood House

Despite his economic successes as a plantation owner and financier, Pickens did not forsake politics with his move to Alabama. He returned to public service in 1819 as a delegate to Alabama’s constitutional convention, representing Washington County. At that time, he was aligned with Gov. William Wyatt Bibb‘s Broad River faction of Georgians. But Pickens, sensitive to shifts in the popular mood, began to distance himself from the interest group in 1820. He built his political fortune in Alabama by mounting a populist challenge to Bibb’s political machine. During the boom period that preceded the Panic of 1819, many Alabamians had engaged in various kinds of speculation, and no group was more successful at these questionable actions than the transplanted Georgians of the Tennessee Valley. Associated with the Planters and Merchants Bank of Huntsville, the Broad River faction amassed wealth and power commensurate with their title of the “Royal Party.” When prosperity collapsed in 1819 and depression lingered into the 1820s, many Alabamians, struggling to stay afloat in a sea of debt, sought scapegoats for their predicament. None fit the bill so well as the Royal Party and its Huntsville bank, which had suspended specie payments during the economic crisis. In north Alabama, popular animosity toward the bank and its supporters tainted the Georgia faction, significantly weakening its power at the very same time as its leader, William Bibb, lay dying. Israel Pickens ran against the Georgians in the 1821 governor’s race, defeating physician Henry Chambers, a director of the Planters and Merchants Bank, by a vote of 9,616 to 7,129, although some sources report Pickens receiving 9,114 votes.

Greenwood House

Despite his economic successes as a plantation owner and financier, Pickens did not forsake politics with his move to Alabama. He returned to public service in 1819 as a delegate to Alabama’s constitutional convention, representing Washington County. At that time, he was aligned with Gov. William Wyatt Bibb‘s Broad River faction of Georgians. But Pickens, sensitive to shifts in the popular mood, began to distance himself from the interest group in 1820. He built his political fortune in Alabama by mounting a populist challenge to Bibb’s political machine. During the boom period that preceded the Panic of 1819, many Alabamians had engaged in various kinds of speculation, and no group was more successful at these questionable actions than the transplanted Georgians of the Tennessee Valley. Associated with the Planters and Merchants Bank of Huntsville, the Broad River faction amassed wealth and power commensurate with their title of the “Royal Party.” When prosperity collapsed in 1819 and depression lingered into the 1820s, many Alabamians, struggling to stay afloat in a sea of debt, sought scapegoats for their predicament. None fit the bill so well as the Royal Party and its Huntsville bank, which had suspended specie payments during the economic crisis. In north Alabama, popular animosity toward the bank and its supporters tainted the Georgia faction, significantly weakening its power at the very same time as its leader, William Bibb, lay dying. Israel Pickens ran against the Georgians in the 1821 governor’s race, defeating physician Henry Chambers, a director of the Planters and Merchants Bank, by a vote of 9,616 to 7,129, although some sources report Pickens receiving 9,114 votes.

Elected Governor

Pickens used popular resentment toward the Royal Party to ride into the governorship and crush the supremacy of the Georgia faction. He artfully used this resentment to push through the creation of Alabama’s state bank, his greatest achievement. Although public support for such an institution was growing in the wake of the Panic of 1819, Pickens still had to demonstrate great skill and patience in laying the groundwork for state involvement in the economy. He first countered a challenge by the legislative friends of the Planters and Merchants Bank, vetoing a bill in 1821 that would have committed substantial public funds to a state institution dominated by private banks.

In his message to the assembly the following year, Pickens argued that the charter of a Bank of Alabama had to give the state control over its direction commensurate with its interest in invested capital. Pickens also went on the offensive against the Planters and Merchants Bank that year, although he moved cautiously. Because much of the economic activity of the state depended on the notes of that bank, destroying it before establishing a state-controlled substitute would prove economically and politically unsound. Pickens put pressure on the Huntsville bank by publicly announcing that he had ordered a court investigation into whether its suspension of specie payments to note holders violated the bank’s charter. Supporters of the Planters and Merchants Bank in the legislature suddenly were willing to deal with the governor and declared that the bank would resume specie payments by the end of 1823 or voluntarily forfeit its charter. Pickens had achieved what he wanted; north Alabama would have a circulating currency for a year, and the Huntsville bank had essentially ratified the instrument of its own death. It never fully resumed specie payments and lost its charter early in 1825.

Personal Tragedy

In 1823, Pickens again defeated Chambers, and his allies gained control of both houses of the legislature. Those political fortunes were offset by personal tragedy, when Pickens’ wife and infant son died soon after the election. He dealt with his grief through hard work, redoubling his efforts to establish the state bank. With the Royal Party chastened by the election outcome, his bank legislation passed in 1823, and the Bank of Alabama opened in 1824. The bank had an initial capitalization of more than $200,000 and was to be managed by a president and board of directors elected annually by the legislature.

But Pickens actually had to amass the money needed to open the bank. He convinced the legislature in his first term to invest $100,000 of funds set aside for a state university. Pickens looked forward to the establishment of the University of Alabama, but the bank took first priority. He skillfully delayed the selection of a campus site and won the approval of the university’s board of directors to invest pledged funds in the bank rather than in the construction of classroom buildings. The rest of the bank’s money came from state bonds sold on the New York market and from the sale of federal land grants reserved for financing transportation improvements in Alabama. The governor’s brother, Andrew, became the first president of the state bank. Although the Bank of Alabama later lost the confidence of the people and collapsed under charges of mismanagement during another national depression, its creation in 1824 marked a significant step in the development of state power over economic affairs. For many years, its profits paid the cost of running Alabama’s state government.

Political Highwire

Pickens used popular hostility toward the aristocratic pretensions of the Georgians to his advantage. He failed, however, to anticipate the overwhelming popularity of Andrew Jackson among the people of Alabama when he supported Jackson’s opponent, John Quincy Adams, in the election of 1824. Party alignments had not yet coalesced in this era, and several prominent politicians jockeyed for position in the presidential election, including William Crawford, the national leader of Alabama’s Georgia faction. Still, Pickens was smart enough to praise Jackson’s recent military exploits in Florida and downplayed opposition to his presidential ambitions. Thus, Pickens’s support of Adams did no real damage to the governor’s reputation.

In 1825, Pickens played host to military hero the Marquis de Lafayette, who was touring the country to the great acclaim of Americans grateful for his support in the Revolutionary War. Lafayette, accompanied by his dog, Quiz, entered Alabama through Creek Nation lands. He then proceeded to Montgomery, where he was welcomed by the governor and entertained at a lavish ball. From Montgomery, Lafayette travelled to Cahawba, then the state capital, where he enjoyed another ball and a more informal barbecue, and then he journeyed on to Mobile. Governor Pickens supervised every detail of the visit, from hiring a New Orleans band to play at the ball to selecting the military officers who escorted the old general through the state. Lafayette’s visit cost Alabama more than $15,000, but most citizens were pleased that he had honored them with his presence.

Israel Pickens’ former opponent, Henry Chambers, died early in 1825 before claiming the U.S. Senate seat to which he had been elected. The following year, Pickens’s personally chosen successor, John Murphy, granted Pickens the interim appointment as Alabama’s junior senator, thus violating the gentleman’s agreement that the state’s U.S. senators would be chosen from different sections of the state, before senators were popularly elected. Pickens’s health was poor, and he spent much of the congressional session of 1826 bedridden. Tuberculosis and fevers forced his resignation at the end of the year and led him to Cuba, where he hoped warmer weather would ease his sufferings. Instead, Pickens’s condition deteriorated, and he died there on April 24, 1827, leaving behind a daughter, two sons, and a legacy as the “father” of many of the foundations of Alabama’s young government. He was interred at his home near Greensboro, in present-day Hale County.

Further Reading

- Abernathy, Thomas Perkins. The Formative Period in Alabama, 1815-1828. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1965.

- Bailey, Hugh C. “Israel Pickens, Peoples’ Politician.” Alabama Review 17 (1964): 83-101.

- Brantley, William H. Three Capitals: A Book About the First Three Capitals of Alabama: St. Stephens, Huntsville, and Cahawba. 1947. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

- Dupre, Daniel S. Transforming the Cotton Frontier: Madison County, Alabama, 1800-1840. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997.