Alabama Bourbons

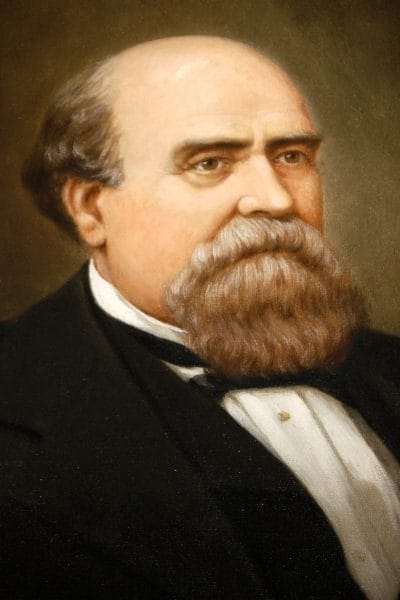

George S. Houston

The term Bourbon was used nationally to describe conservative Democrats active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Alabama and the South. In Alabama, it has also been used to identify conservative Democrats who wanted to end Reconstruction and restore as much of the pre-Civil War order that was practical given the defeat of the Confederacy and the abolition of slavery. The term also included other conservative Democrats (sometimes called “Redeemers”) who, in addition to ending Reconstruction, wanted to create a “New South” in which business and industry would flourish. In Alabama, one of two large factions was made up mostly of plantation owners from the Black Belt and the Tennessee Valley. The other faction was dominated by industrial interests in the Birmingham District and north Alabama, although commercial concerns in cities like Mobile usually fell into this category, as did merchants in towns both large and small. Both factions wanted to keep power in the hands of wealthy, propertied classes and deny political power to poor whites and blacks. The origin of the term is obscure; however, it seems to be most often associated with the reactionary Bourbon Dynasty of France that attempted to undo what was done by the French Revolution. In Alabama and the South, Bourbon Democrats worked to undo what was done by the Civil War and Reconstruction.

George S. Houston

The term Bourbon was used nationally to describe conservative Democrats active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Alabama and the South. In Alabama, it has also been used to identify conservative Democrats who wanted to end Reconstruction and restore as much of the pre-Civil War order that was practical given the defeat of the Confederacy and the abolition of slavery. The term also included other conservative Democrats (sometimes called “Redeemers”) who, in addition to ending Reconstruction, wanted to create a “New South” in which business and industry would flourish. In Alabama, one of two large factions was made up mostly of plantation owners from the Black Belt and the Tennessee Valley. The other faction was dominated by industrial interests in the Birmingham District and north Alabama, although commercial concerns in cities like Mobile usually fell into this category, as did merchants in towns both large and small. Both factions wanted to keep power in the hands of wealthy, propertied classes and deny political power to poor whites and blacks. The origin of the term is obscure; however, it seems to be most often associated with the reactionary Bourbon Dynasty of France that attempted to undo what was done by the French Revolution. In Alabama and the South, Bourbon Democrats worked to undo what was done by the Civil War and Reconstruction.

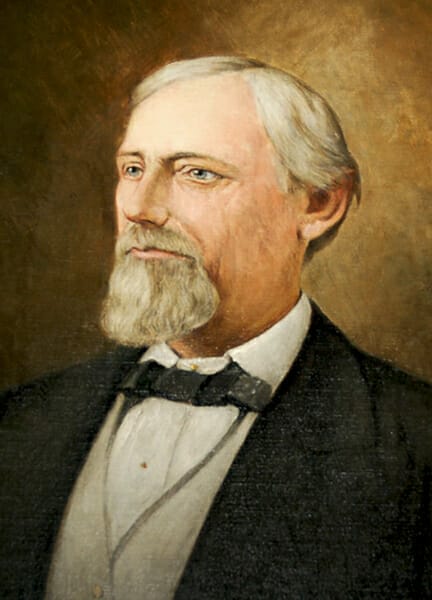

Rufus W. Cobb

Although they differed on many issues, these Bourbon factions agreed that taxes should be kept low, state services should be minimal, and mine, mill, and field labor should be under their control. Critical to achieving these goals was the dominance of the Democratic Party, which they controlled and through which they intended to maintain white, upper-class supremacy. Coming to power in the mid-1870s at the end of Reconstruction—an end they hastened through violence and electoral fraud—Alabama Bourbons enshrined their values in the Constitution of 1875, a document the small farmer class supported because they were as concerned about taxes as the wealthy property owners. Although this constitution did little to promote the sort of commerce advocates of a New South wanted, it allowed industrial interests to operate with little state interference, so they accepted it with few complaints.

Rufus W. Cobb

Although they differed on many issues, these Bourbon factions agreed that taxes should be kept low, state services should be minimal, and mine, mill, and field labor should be under their control. Critical to achieving these goals was the dominance of the Democratic Party, which they controlled and through which they intended to maintain white, upper-class supremacy. Coming to power in the mid-1870s at the end of Reconstruction—an end they hastened through violence and electoral fraud—Alabama Bourbons enshrined their values in the Constitution of 1875, a document the small farmer class supported because they were as concerned about taxes as the wealthy property owners. Although this constitution did little to promote the sort of commerce advocates of a New South wanted, it allowed industrial interests to operate with little state interference, so they accepted it with few complaints.

The Constitution of 1875 did not, however, write white supremacy into law by imposing restrictions on African American voters. Afraid that violating the 15th Amendment would result in a loss of congressional representation or, worse yet, the return of federal troops, the Bourbons shied away from overt disfranchisement. This later proved to their advantage, for had there been no black vote when Bourbon dominance was challenged by the Populist movement that arose in the late 1880s, plantation owners in the Black Belt would have had no votes to steal and thus no way to defend their position and the prerogatives that came with it.

In addition to illegally “counting in and counting out” black votes (counting the votes one wanted while ignoring the others), Bourbons were able to use the Democratic Party machinery to their advantage. Their convention delegates chose candidates who were seated by a Bourbon-controlled committee, ensuring that only those individuals who shared their goals would be on Democratic ballots.

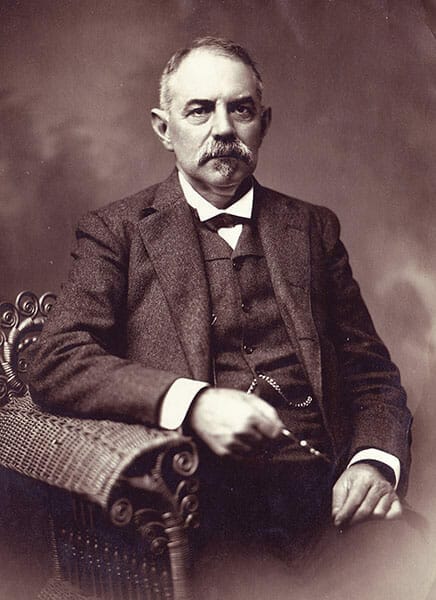

Thomas Goode Jones

The Populist movement revealed that the small farmers who had supported the 1875 Constitution were not dependable supporters of the rest of the Bourbon platform, so conservatives began looking for ways to disfranchise these opponents. The Sayre Law, passed in 1893, was the first effective legislation to do this. It changed the wording of the ballot, which disadvantaged illiterate voters, and also required voters to register in May, which inconvenienced many farmers. For most Bourbons, however, these changes were not enough, and after another manipulated election in April of 1901, they met in convention a month later to rewrite the constitution to disenfranchise most blacks and many whites.

Thomas Goode Jones

The Populist movement revealed that the small farmers who had supported the 1875 Constitution were not dependable supporters of the rest of the Bourbon platform, so conservatives began looking for ways to disfranchise these opponents. The Sayre Law, passed in 1893, was the first effective legislation to do this. It changed the wording of the ballot, which disadvantaged illiterate voters, and also required voters to register in May, which inconvenienced many farmers. For most Bourbons, however, these changes were not enough, and after another manipulated election in April of 1901, they met in convention a month later to rewrite the constitution to disenfranchise most blacks and many whites.

Alabama Bourbons had seen how other states, Mississippi in particular, had used carefully crafted voter qualifications, including literacy tests, poll taxes, ownership of property, and “good character” tests, to disfranchise black voters on the basis of something other than race and thus bypass the 15th Amendment altogether. Free now from the fear of federal intervention, they gathered in Montgomery determined to constitutionally put power in the hands of white men whose circumstances were much like their own.

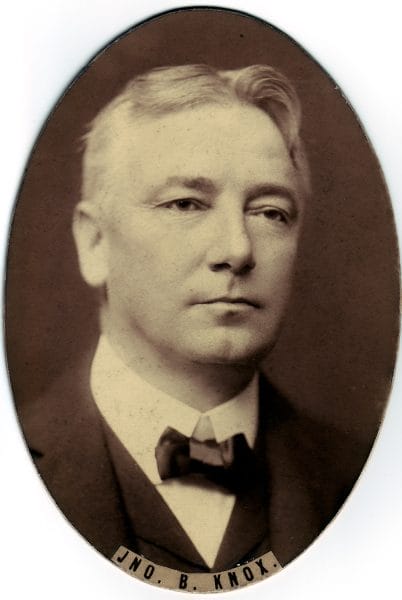

Knox, John B.

The convention delegates consisted mostly of the lawyers, plantation owners, and businessmen who made up the core Bourbon constituency. John B. Knox of Anniston, a lawyer with corporate ties, was chosen to preside over the group and in his opening remarks made clear how the Bourbon interpretation of history justified what was about to be done. He reminded delegates of their perceived indignities: U.S. military troops helping elect freedmen who, together with unscrupulous whites, wasted money, created debts, and increased taxes, thus forcing Bourbons to steal votes out of necessity and self-preservation. He also said that the Bourbons were going to establish white supremacy through legal means, not by “force or fraud.” Knox claimed this was justified by declaring the moral and intellectual inferiority of blacks, a pretense that race was not at the heart of the matter.

Knox, John B.

The convention delegates consisted mostly of the lawyers, plantation owners, and businessmen who made up the core Bourbon constituency. John B. Knox of Anniston, a lawyer with corporate ties, was chosen to preside over the group and in his opening remarks made clear how the Bourbon interpretation of history justified what was about to be done. He reminded delegates of their perceived indignities: U.S. military troops helping elect freedmen who, together with unscrupulous whites, wasted money, created debts, and increased taxes, thus forcing Bourbons to steal votes out of necessity and self-preservation. He also said that the Bourbons were going to establish white supremacy through legal means, not by “force or fraud.” Knox claimed this was justified by declaring the moral and intellectual inferiority of blacks, a pretense that race was not at the heart of the matter.

The Bourbon-controlled convention adopted a host of requirements that disfranchised not only African Americans but in time a large number of poor whites as well. The rest of the Constitution of 1901 kept in place most of the same limitations on taxing and government power that had been in its 1875 predecessor. Thus low taxes (particularly on property), weak government, and white supremacy—the core concerns of the Bourbons—became the law of the land.

William Calvin Oates

By virtue of the Constitution of 1901, Bourbon plantation owners had a labor force they could control and untaxed property with which they could do as they wished. That same document gave industrialists in Montgomery a government that would help them keep labor in line and would hinder them little in the way they did business. The Bourbons had fixed the system so that they controlled the legislature and ensured that almost all changes in state, county, and local governance had to go through the legislature. It would be well past mid-century before some reforms, particularly the return of voting rights to blacks and a loosening of white supremacy, came about. Other aspects of the Bourbon handiwork remain evident today, particularly low property taxes.

William Calvin Oates

By virtue of the Constitution of 1901, Bourbon plantation owners had a labor force they could control and untaxed property with which they could do as they wished. That same document gave industrialists in Montgomery a government that would help them keep labor in line and would hinder them little in the way they did business. The Bourbons had fixed the system so that they controlled the legislature and ensured that almost all changes in state, county, and local governance had to go through the legislature. It would be well past mid-century before some reforms, particularly the return of voting rights to blacks and a loosening of white supremacy, came about. Other aspects of the Bourbon handiwork remain evident today, particularly low property taxes.

Nationally, Bourbon Democrats slipped from power after 1904. In the South and in Alabama, however, people with Bourbon interests and sentiments remained in office well into the second half of the twentieth century. Some are still in office today.

Additional Resources

Going, Allen J. Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874-1890. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1951.

Hackney, Sheldon. Populism to Progressivism in Alabama. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970.

Jackson, Harvey H. Inside Alabama: A Personal History of My State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

Thomson, Baily, ed. A Century of Controversy: Constitutional Reform in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

Webb, Samuel L. Two-Party Politics in the One-Party South: Alabama’s Hill Country, 1874-1920. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997.