Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday

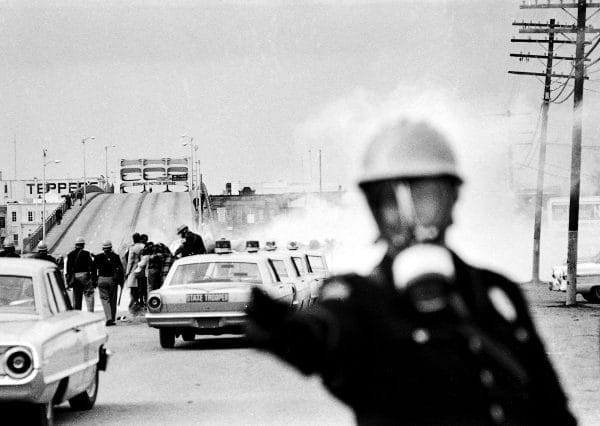

“Bloody Sunday” refers to the March 7, 1965, civil rights march that was supposed to go from Selma to the capitol in Montgomery to protest the shooting death of activist Jimmie Lee Jackson. The roughly 600 marchers were violently driven back by Alabama State Troopers, Dallas County Sheriff’s deputies, and a horse-mounted posse after they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The state and county officers beat and gassed the unarmed marchers in an attack, and media coverage of the event shocked the nation and led ultimately to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The descriptive term appeared in relation to the events within days in the national media.

Bloody Sunday

“Bloody Sunday” refers to the March 7, 1965, civil rights march that was supposed to go from Selma to the capitol in Montgomery to protest the shooting death of activist Jimmie Lee Jackson. The roughly 600 marchers were violently driven back by Alabama State Troopers, Dallas County Sheriff’s deputies, and a horse-mounted posse after they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The state and county officers beat and gassed the unarmed marchers in an attack, and media coverage of the event shocked the nation and led ultimately to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The descriptive term appeared in relation to the events within days in the national media.

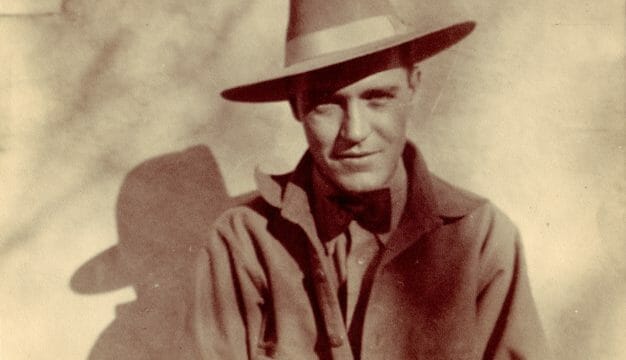

James Bevel

The catalyst for the march was the death of 26-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson on February 26. He was shot in the stomach on February 18, 1965, by Alabama State Trooper James Fowler while the troopers were breaking up a peaceful protest in Marion, Perry County. Jackson was then taken the 50 miles to Selma’s Good Samaritan Hospital for treatment, where he died eight days later. At a memorial service for Jackson on February 28, Rev. James Bevel of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) called for blacks to follow the example of the biblical Queen Esther, who risked her life by going to the king of Persia to appeal for her people. Bevel stated that the activists must similarly march to Montgomery to demand protection from Gov. George C. Wallace. Two days later, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. offered the support of the SCLC to head up a march from Selma to Montgomery on Sunday, March 7, to protest Jackson’s death and to push for voting rights.

James Bevel

The catalyst for the march was the death of 26-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson on February 26. He was shot in the stomach on February 18, 1965, by Alabama State Trooper James Fowler while the troopers were breaking up a peaceful protest in Marion, Perry County. Jackson was then taken the 50 miles to Selma’s Good Samaritan Hospital for treatment, where he died eight days later. At a memorial service for Jackson on February 28, Rev. James Bevel of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) called for blacks to follow the example of the biblical Queen Esther, who risked her life by going to the king of Persia to appeal for her people. Bevel stated that the activists must similarly march to Montgomery to demand protection from Gov. George C. Wallace. Two days later, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. offered the support of the SCLC to head up a march from Selma to Montgomery on Sunday, March 7, to protest Jackson’s death and to push for voting rights.

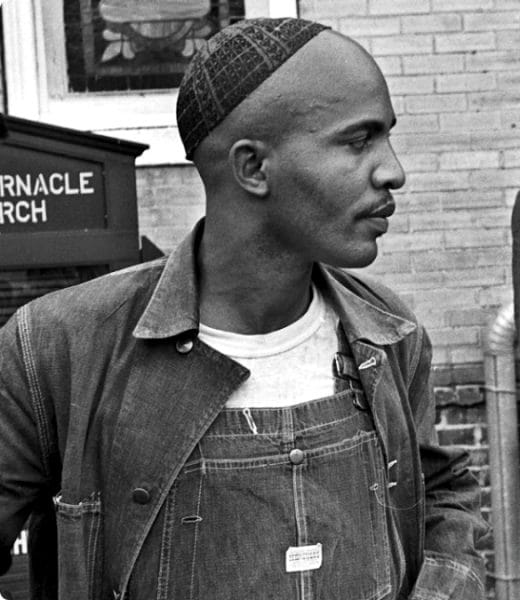

The members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) refused to support the march, however, because they believed that the objectives of the march did not justify the danger. But its leaders agreed to let SNCC president John Lewis take part as an individual. Governor Wallace, who had hesitated over whether or not to permit the march, finally decided to direct the Alabama State Troopers to stop the marchers once they had left the city limits of Selma by crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Wallace asked for the city police and county police to assist the troopers. Selma’s public safety director Wilson Baker, who was in charge of the city police, refused to let his men join the troopers in what he feared would become a brutal attack on the marchers. He begged Selma mayor Joe Smitherman to let him head off such a clash by arresting the marchers before they crossed the bridge. Smitherman, who had complete faith in Wallace’s promise to disperse the marchers without undue violence, refused.

Wilson Baker and Jim Clark

On Sunday, March 7, the state troopers, under the command of Maj. John Cloud, along with Sheriff Jim Clark‘s deputies and mounted posse, were assembled at the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge by noon. The march did not begin on time, however, because King had not returned from Atlanta, and there was a good deal of confusion about whether or not to postpone the march. Finally, King was reached by phone and gave permission to proceed in his absence. When the marchers first left Brown Chapel AME Church at 1:40 p.m., they were stopped by Wilson Baker, who ordered them to follow the usual rules for such events: marching two-by-two, five feet apart. The demonstrators went to a nearby playground to regroup and set out once again at 2:18 p.m. Under the leadership of Hosea Williams of SCLC and John Lewis of SNCC, they marched south on Sylvan Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard) to Alabama Avenue, then west on Alabama to Broad Street, and finally south on Broad across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Wilson Baker and Jim Clark

On Sunday, March 7, the state troopers, under the command of Maj. John Cloud, along with Sheriff Jim Clark‘s deputies and mounted posse, were assembled at the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge by noon. The march did not begin on time, however, because King had not returned from Atlanta, and there was a good deal of confusion about whether or not to postpone the march. Finally, King was reached by phone and gave permission to proceed in his absence. When the marchers first left Brown Chapel AME Church at 1:40 p.m., they were stopped by Wilson Baker, who ordered them to follow the usual rules for such events: marching two-by-two, five feet apart. The demonstrators went to a nearby playground to regroup and set out once again at 2:18 p.m. Under the leadership of Hosea Williams of SCLC and John Lewis of SNCC, they marched south on Sylvan Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard) to Alabama Avenue, then west on Alabama to Broad Street, and finally south on Broad across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Cloud announced that the governor had forbidden the march and gave the marchers two minutes to turn back. When the marchers did not obey promptly, he ordered the troopers to advance. At first, the troopers simply shoved the marchers back with billy clubs held at both ends, but soon they began lashing out. They deployed 40 canisters of tear gas, 12 cans of smoke, and 8 cans of nausea gas, and began chasing the marchers back across the bridge. (Cloud later claimed that Clark set off the first canister of tear gas by mistake.) The troopers and the mounted posse pursued the fleeing marchers all the way back to Brown Chapel, beating people as they went.

John Lewis Injured During March

Wilson Baker then confronted Clark and told him to take control of his men and leave the area. (Baker would be remembered in a positive light for his actions. He defeated Clark in the 1966 race for sheriff with the support of newly enfranchised blacks.) Clark reluctantly withdrew his forces, making it possible for ambulances to pick up the injured and race them to Selma’s two black hospitals, Good Samaritan and Burwell Infirmary. Fifty-six patients were treated at the two hospitals, with 18 being admitted overnight, including John Lewis, who had a fractured skull.

John Lewis Injured During March

Wilson Baker then confronted Clark and told him to take control of his men and leave the area. (Baker would be remembered in a positive light for his actions. He defeated Clark in the 1966 race for sheriff with the support of newly enfranchised blacks.) Clark reluctantly withdrew his forces, making it possible for ambulances to pick up the injured and race them to Selma’s two black hospitals, Good Samaritan and Burwell Infirmary. Fifty-six patients were treated at the two hospitals, with 18 being admitted overnight, including John Lewis, who had a fractured skull.

The television coverage of the violence shocked the nation. It provoked an outpouring of support for the voting rights movement from whites throughout the country: priests, ministers, nuns, rabbis, labor leaders, students, and ordinary citizens poured into Selma to stand with the marchers. An estimated 800 volunteers from 22 states arrived in Selma in the days after Bloody Sunday. Pres. Lyndon Johnson and key members of Congress who had been dubious about the need for a voting rights bill now committed themselves to its passage. Governor Wallace announced that the violence was not supposed to happen and rebuked Mayor Smitherman and Sheriff Clark for allowing it.

Marching to Montgomery

On Tuesday, March 9, the marchers made a second attempt, led by King, but turned back at the end of the bridge, earning the day the nickname “Turnaround Tuesday.” A third and successful attempt began under the protection of the Alabama National Guard (which had been placed under federal control by President Johnson) on Sunday, March 21, two weeks after the initial effort. The marchers finally reached Montgomery on Thursday, March 25. The Voting Rights Bill that King, Lewis, and so many other civil rights leaders had sought was signed into law August 6, 1965.

Marching to Montgomery

On Tuesday, March 9, the marchers made a second attempt, led by King, but turned back at the end of the bridge, earning the day the nickname “Turnaround Tuesday.” A third and successful attempt began under the protection of the Alabama National Guard (which had been placed under federal control by President Johnson) on Sunday, March 21, two weeks after the initial effort. The marchers finally reached Montgomery on Thursday, March 25. The Voting Rights Bill that King, Lewis, and so many other civil rights leaders had sought was signed into law August 6, 1965.

On March 7, 2015, Pres. Barack Obama attended the 50th anniversary commemoration of Bloody Sunday and also signed into law a bill awarding a Congressional Gold Medal to those individuals who participated in the three Selma to Montgomery marches. The bill was originally introduced by Rep. Terri Sewell of Alabama’s Seventh Congressional District, which includes Selma and portions of Montgomery. A companion bill was introduced by Alabama senator Jeff Sessions.

Additional Resources

Fager, Charles. Selma 1965: The March That Changed the South. Boston: Beacon Press, 1975.

Thorton, J. Mills, III. Dividing Lines, Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.