Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

The “stand in the schoolhouse door” incident was Alabama Governor George Wallace’s symbolic opposition to school integration imposed by the federal government. The June 11, 1963, action occurred in the doorway of Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama and was intended to prevent the enrollment of two black students, James Hood and Vivian Malone. The day marks the beginning of school desegregation in the state. Moreover, it was an event that would continue to haunt both Wallace and the state for years to come. The event received national news coverage, providing Wallace a stage for launching four unsuccessful presidential campaigns on his stance in favor of states’ rights.

Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

The “stand in the schoolhouse door” incident was Alabama Governor George Wallace’s symbolic opposition to school integration imposed by the federal government. The June 11, 1963, action occurred in the doorway of Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama and was intended to prevent the enrollment of two black students, James Hood and Vivian Malone. The day marks the beginning of school desegregation in the state. Moreover, it was an event that would continue to haunt both Wallace and the state for years to come. The event received national news coverage, providing Wallace a stage for launching four unsuccessful presidential campaigns on his stance in favor of states’ rights.

Wallace, who served as Alabama’s governor for four terms that spanned from the 1960s to the 1980s, was originally elected as a segregationist. He gained notoriety for his 1963 inauguration speech, in which he declared his support for “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Wallace had also mentioned during that campaign that he would block, even physically, any attempt to integrate schools. He gained national attention when he challenged the enrollment of two black students to the University of Alabama. The governor argued that the constitution gave the states, not the federal government, authority over public schools and universities.

Vivian Malone

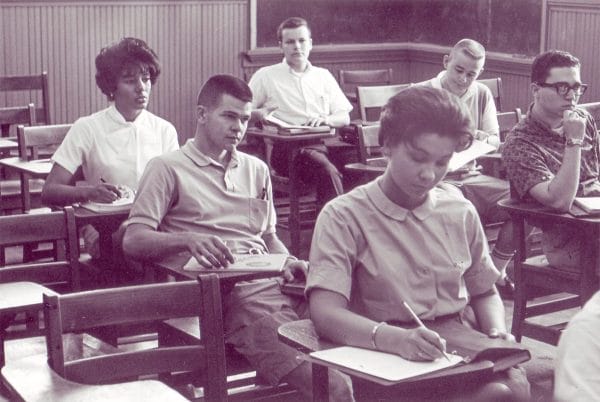

James Alexander Hood, of Gadsden, and Vivian Juanita Malone, of Mobile, applied to the school in November 1961. They were not the first black students to apply or even attend the school. Autherine Juanita Lucy, a graduate student from Shiloh, had applied, been accepted to, and then attended the university for three days in 1956. But after she was threatened with mob violence, university officials said the school could no longer protect her. She filed an unsuccessful lawsuit against the university, which was used as an excuse to expel her permanently.

Vivian Malone

James Alexander Hood, of Gadsden, and Vivian Juanita Malone, of Mobile, applied to the school in November 1961. They were not the first black students to apply or even attend the school. Autherine Juanita Lucy, a graduate student from Shiloh, had applied, been accepted to, and then attended the university for three days in 1956. But after she was threatened with mob violence, university officials said the school could no longer protect her. She filed an unsuccessful lawsuit against the university, which was used as an excuse to expel her permanently.

Hood and Malone were scheduled to enroll on June 11. That morning, Wallace, flanked by state troopers, positioned himself at the entrance to Foster Auditorium. On the authority of President John F. Kennedy, U.S. Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, accompanied by federal marshals and the Alabama National Guard, confronted Wallace and asked him to allow the students entrance. Wallace refused and delivered a speech denouncing the federal government. In his speech, which sounded much like an official proclamation that politicians often read at government meetings, Wallace complained that the “central government” was encroaching on the rights and sovereignty of Alabama. He cited the 10th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which established the states’ authority in the absence of federal authority. After speaking, he placed himself in the doorway of Foster Auditorium and refused to move.

Katzenbach sent Hood and Malone to the dormitories. Attorney General Robert Kennedy asked Katzenbach what Wallace’s response was, and Katzenbach said Wallace’s answer was “no,” signaling it was time to authorize the National Guard to remove Wallace. Both President Kennedy and the attorney general knew Wallace would step aside but were not sure how he would do it. Guardsmen even practiced how they would physically remove the governor. Under President Kennedy’s authorization, Brig. Gen. Henry V. Graham traveled to Tuscaloosa to remove Wallace. Upon his arrival on the afternoon of June 11, Graham told Wallace that it was his “sad duty” to tell the governor to step aside. Wallace made a quick final statement and complied. Malone and Hood were then able to enter the auditorium and register for classes.

Malone graduated from Alabama in 1965 with a degree in personnel management. She died Oct. 13, 2005, in Atlanta, following complications from a stroke. Hood withdrew a few months after enrollment but returned to earn a doctorate degree in 1997. Wallace’s stand on segregation would plague him politically for the rest of his life, although he had a change of heart on race and segregation. He ran a final successful campaign for Alabama governor in the 1980s, an election he won in part because of the black vote. Wallace even befriended Hood later in life. The legacy of Wallace’s stand in the schoolhouse door is two-fold. It is an enduring stain on Alabama’s education record and a sad testament to the treatment of its own people. It also served as a turning point for the state and its first steps toward racial equality.

Further Reading

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

- Clark, E. Culpepper. The Schoolhouse Door: Segregation’s Last Stand at the University of Alabama. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Elliot, Debbie. “Wallace in the Schoolhouse Door: Marking the 40th Anniversary of Alabama’s Civil Rights Standoff.” Morning Edition, National Public Radio, June 11, 2003.

- Mayfield, Mark, and Jill Lawrence. “Wallace: Name Will Always Be Linked to Segregation.” USA Today, September 14, 1998.