Louise Wooster

Louise Catherine Wooster (1842-1913) was the madam of an exclusive house of prostitution in Birmingham in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Her enduring fame is based on facts, self-inventions, and legendary re-inventions. Wooster’s decision to care for the sick during Birmingham’s deadly 1873 cholera epidemic was authentically heroic. Other aspects of her life, including an unsubstantiated affair with John Wilkes Booth, were fabrications designed to make her appear larger than life. She crafted her persona so carefully that it is very difficult to know what was real and what was invented.

The Real Louise Wooster

Louise Wooster’s Fourth Avenue Buildings

Wooster’s presumed real life was interesting but largely unremarkable. Because so much of Wooster’s biography is invented, the true facts of her life are vague. She was born in Tuscaloosa to William and Mary Wooster on June 12, 1842, and was one of several children. By the time Louise was seven, the family lived in Mobile. Her parents’ deaths (her father in 1851, her mother in 1857) left the children destitute. When Louise was about 15, her older sister, Margaret, became a prostitute, two younger sisters were placed in Mobile’s Protestant Orphan Asylum, and Louise went to New Orleans to live with a married sister. She returned to Mobile with a forged a letter and removed her sisters from the orphanage. The girls went to live with a male family friend with whom Louise had a sexual relationship. Later, Wooster entered a Montgomery brothel. Wooster was in Birmingham by at least 1873 and was among the prostitutes who received public affirmation after the deadly 1873 cholera epidemic because they cared for the sick and prepared bodies for burial.

Louise Wooster’s Fourth Avenue Buildings

Wooster’s presumed real life was interesting but largely unremarkable. Because so much of Wooster’s biography is invented, the true facts of her life are vague. She was born in Tuscaloosa to William and Mary Wooster on June 12, 1842, and was one of several children. By the time Louise was seven, the family lived in Mobile. Her parents’ deaths (her father in 1851, her mother in 1857) left the children destitute. When Louise was about 15, her older sister, Margaret, became a prostitute, two younger sisters were placed in Mobile’s Protestant Orphan Asylum, and Louise went to New Orleans to live with a married sister. She returned to Mobile with a forged a letter and removed her sisters from the orphanage. The girls went to live with a male family friend with whom Louise had a sexual relationship. Later, Wooster entered a Montgomery brothel. Wooster was in Birmingham by at least 1873 and was among the prostitutes who received public affirmation after the deadly 1873 cholera epidemic because they cared for the sick and prepared bodies for burial.

In the 1880s, Wooster bought a two-story home on Fourth Avenue North and an adjacent building that became one of Birmingham’s “high-class” brothels. Near city hall, saloons, and the police station, the location offered Wooster access to influence, customers, alcohol, and police protection. She continued to prosper. By 1887, Wooster’s considerable assets included land, buildings, furniture, and jewelry. She held the funeral of at least one of her prostitutes at her brothel. She buried several others and at least two of their infants in her Oak Hill Cemetery plot.

In 1890, Wooster prompted American newspapers, including the Cincinnati Enquirer, to report her belief that John Wilkes Booth was still alive. She tantalizingly claimed she had been the actor’s lover prior to his assassination of Pres. Abraham Lincoln. Wooster retired in 1901 and died on May 16, 1913, of kidney disease and was buried in Oak Hill.

The Invented Louise Wooster

The Autobiography of a Magdalen

Newspapers and Wooster’s The Autobiography of a Magdalen (1911), probably co-written with a Birmingham minister, invented a substantially different woman. The refined “Miss Wooster” was connected to the most important people and events of American history. Her father was a New Englander of “old Puritan stock,” her mother was the daughter of a “wealthy Southern planter,” and she was educated in fashionable boarding schools in aristocratic Mobile. She wanted only marriage and a “lovely little cottage surrounded by flowers.” Her mother died when she was only 10—Wooster strategically lowered the age from 15—extracting a deathbed promise from Louise to protect her younger sisters. A series of men misrepresenting themselves as “gentlemen” callously betrayed her. Despite her efforts, polite society allowed no return from her “fall.” Nonetheless, the invented Wooster travelled in the world’s finest social circles, studied human nature, and devoured Shakespeare. The book compares her to Macbeth and Hamlet and borrows Polonius’ advice to Laertes to describe her clothing as “costly as my purse could buy, rich but not gaudy.”

The Autobiography of a Magdalen

Newspapers and Wooster’s The Autobiography of a Magdalen (1911), probably co-written with a Birmingham minister, invented a substantially different woman. The refined “Miss Wooster” was connected to the most important people and events of American history. Her father was a New Englander of “old Puritan stock,” her mother was the daughter of a “wealthy Southern planter,” and she was educated in fashionable boarding schools in aristocratic Mobile. She wanted only marriage and a “lovely little cottage surrounded by flowers.” Her mother died when she was only 10—Wooster strategically lowered the age from 15—extracting a deathbed promise from Louise to protect her younger sisters. A series of men misrepresenting themselves as “gentlemen” callously betrayed her. Despite her efforts, polite society allowed no return from her “fall.” Nonetheless, the invented Wooster travelled in the world’s finest social circles, studied human nature, and devoured Shakespeare. The book compares her to Macbeth and Hamlet and borrows Polonius’ advice to Laertes to describe her clothing as “costly as my purse could buy, rich but not gaudy.”

Her numerous affairs, probably invented, were only with important men. The Autobiography claims she lived with a son of “one of Alabama’s most important criminal lawyers,” then with a wealthy gentleman who lost his money gambling. Her remarkable claim of an affair with John Wilkes Booth, undocumented outside her interviews and autobiography, presents her as the true love of America’s heartthrob leading man prior to his assassination of Lincoln and thus as a supporting actor in one of the most significant events in American history.

Although Wooster’s autobiography is factually unreliable, it shows a woman who thought her life had enduring meaning. It tries to expose Victorian America’s harsh double sexual standard, offers advice to parents hoping to protect their daughters from social ruin, and argues for forgiveness. The most interesting aspect of the Autobiography is its attempt to interpret Wooster’s life in terms of Christianity. The book chastises the Church and harshly portrays “good Christian women” as predators after Wooster’s money.

The title—The Autobiography of a Magdalen—references the popular conclusion that Mary Magdalen was a prostitute. It suggests Wooster was a similarly reviled but authentic follower of Christ. Her mother’s alleged deathbed plea aligns with Jesus’s final instruction to his followers to go into the world to save the lost. The last two chapters describe “True Christianity” and include reflections on Mosaic Law and Wooster’s belief in the apocalyptic Jesus who will reconstruct the present world.

Wooster’s Legacy to Alabama

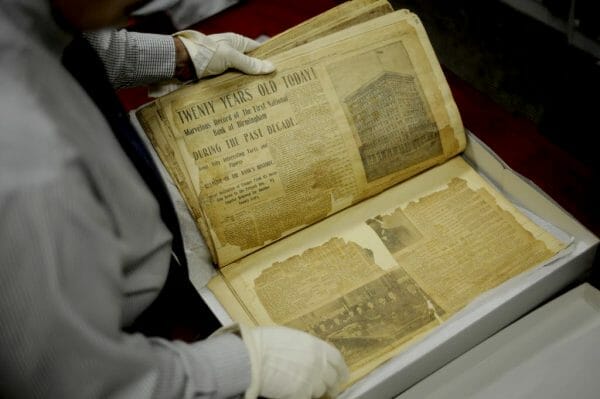

Louise Wooster’s Scrapbook

It was the invented “Lou” Wooster who became the Alabama legend rather than the prostitute who amassed wealth exploiting other women, who attempted suicide, and who drank heavily for many of her 71 years. Her Autobiography is devoid of the brutal realities of prostitution in Birmingham—its close association with poverty created by the cotton mills that supplied “high-class” brothels their “girls” and the young boys who served as night messengers, not to mention the saloons, violent crime, sexually transmitted diseases, and police graft. Birmingham’s notorious “red-light” district does not exist in The Autobiography of a Magdalen. Three things aided Wooster’s re-invention: the recognizable characters (the heartless orphanage matron) and hyperbolic language (“poor penniless orphans!”) of Victorian melodrama, an American preoccupation with romantic versions of prostitution, and the reform interests of the unnamed minister who probably co-wrote her autobiography and who wrote its introduction.

Louise Wooster’s Scrapbook

It was the invented “Lou” Wooster who became the Alabama legend rather than the prostitute who amassed wealth exploiting other women, who attempted suicide, and who drank heavily for many of her 71 years. Her Autobiography is devoid of the brutal realities of prostitution in Birmingham—its close association with poverty created by the cotton mills that supplied “high-class” brothels their “girls” and the young boys who served as night messengers, not to mention the saloons, violent crime, sexually transmitted diseases, and police graft. Birmingham’s notorious “red-light” district does not exist in The Autobiography of a Magdalen. Three things aided Wooster’s re-invention: the recognizable characters (the heartless orphanage matron) and hyperbolic language (“poor penniless orphans!”) of Victorian melodrama, an American preoccupation with romantic versions of prostitution, and the reform interests of the unnamed minister who probably co-wrote her autobiography and who wrote its introduction.

With or without facts, Alabamians continue to re-invent Louise Wooster. Without evidence, fans insist that for Wooster’s funeral Birmingham’s prominent men formed a blocks-long cortege of empty carriages to escort her body to Oak Hill (there were actually few mourners in attendance) and cherish the doubtful theory that Margaret Mitchell based her Gone With the Wind character Belle Watling on her. In 2000, responding to the operatic quality of the legend, Alabama Operaworks commissioned Louise: The Story of a Magdalen and Dorothy Hindman composed the score for Sally M. Gall’s libretto. In 2004, it won the Nancy Van de Vate International Composition Prize for Opera. In 2012, the Birmingham History Center acquired Wooster’s scrapbook from Bertie Jones, whose family previously donates a sofa believed to have belonged to Wooster. Jones’s great grandmother was a friend of Wooster’s and came into possession of several of her belongings.

Further Reading

- James L. Baggett. “Louise Wooster: Birmingham’s Magdalen.” Alabama Heritage 78 (Fall 2005): 24-29.

- James L. Baggett, ed. A Woman of the Town: Louise Wooster, Birmingham’s Magdalen. Birmingham: Birmingham Public Library Press, 2005. Copies available from the Birmingham Public Library.

- Ellin Sterne [Jimmerson]. “Prostitution in Birmingham, Alabama 1890-1925.” M.A. thesis, Samford University, 1977.