Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Alabama

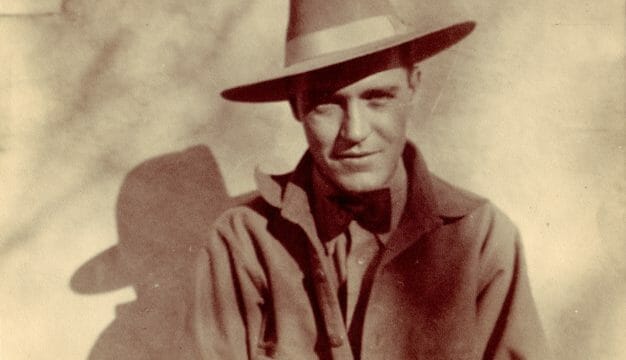

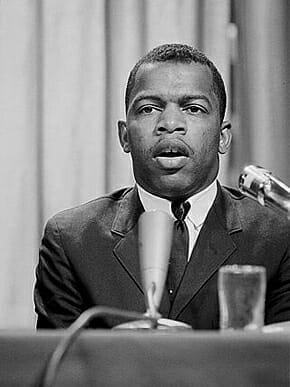

John Lewis

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “Snick”) was founded in Raleigh, North Carolina, in April 1960. SNCC became one of the most important civil rights organizations of the 1960s, and Alabama and Alabamians played vital roles in its efforts. Future Georgia congressman John Lewis, who held the position of SNCC chairperson from the spring of 1963 until May 1966, was from rural Pike County near Troy and was involved with SNCC from its beginnings. Robert “Bob” Zellner, a southern Alabamian whose father was a former Ku Klux Klan member, became SNCC’s first white field secretary in the fall of 1961, having begun participating in civil rights protests while a student at Montgomery’s Huntingdon College. During his work with SNCC, Zellner was beaten and jailed numerous times, yet he continued to fight against racism and discrimination with the organization for most of its existence. Selma’s Bettie Mae Fikes joined the movement while still in high school, taking part in demonstrations, passing out leaflets to register voters, and quickly becoming part of the SNCC Freedom Singers, a group that travelled around the country publicizing and fundraising for the organization. Throughout the 1960s, SNCC became known primarily for holding nonviolent demonstrations, organizing grassroots groups, registering African American voters, and eventually for advocating the philosophy of Black Power.

John Lewis

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “Snick”) was founded in Raleigh, North Carolina, in April 1960. SNCC became one of the most important civil rights organizations of the 1960s, and Alabama and Alabamians played vital roles in its efforts. Future Georgia congressman John Lewis, who held the position of SNCC chairperson from the spring of 1963 until May 1966, was from rural Pike County near Troy and was involved with SNCC from its beginnings. Robert “Bob” Zellner, a southern Alabamian whose father was a former Ku Klux Klan member, became SNCC’s first white field secretary in the fall of 1961, having begun participating in civil rights protests while a student at Montgomery’s Huntingdon College. During his work with SNCC, Zellner was beaten and jailed numerous times, yet he continued to fight against racism and discrimination with the organization for most of its existence. Selma’s Bettie Mae Fikes joined the movement while still in high school, taking part in demonstrations, passing out leaflets to register voters, and quickly becoming part of the SNCC Freedom Singers, a group that travelled around the country publicizing and fundraising for the organization. Throughout the 1960s, SNCC became known primarily for holding nonviolent demonstrations, organizing grassroots groups, registering African American voters, and eventually for advocating the philosophy of Black Power.

SNCC’s origins lay in the student sit-ins against segregation that began on February 1, 1960, when four North Carolina A&T College students sat down at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, and requested service. African Americans were able to purchase goods throughout the department store, but they were not permitted to eat at the lunch counter, and the students sat down to challenge this racist practice. Though they were not served, the following day other students joined in, and by mid-April, sit-ins had occurred in every southern state, with thousands of participants. In many cases, these sit-ins were spontaneous events, but in other areas organized groups had been meeting and planning to take action in the months before the February 1 demonstration. For example, students from several colleges in Nashville, Tennessee, including Alabamian John Lewis (who was studying at Nashville’s American Baptist College), attended nonviolence workshops led by James Lawson, a long-time member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). Over the weekend of April 15-17, 1960, Ella Baker, an activist with decades of experience, and Martin Luther King Jr. gathered nearly 300 of these students to a conference in Raleigh, North Carolina, leading to the founding of SNCC. Originally established as an umbrella organization to coordinate student activists all over the South, SNCC was never a formal membership group. It had elected officials, volunteers, and eventually paid field secretaries, but throughout its existence SNCC also had looser associations, as individuals and student groups—including ones from Talladega College, Tuskegee Institute, Miles College, Birmingham-Southern College, and other Alabama schools—affiliated themselves with SNCC.

Attack on Freedom Riders in Anniston

SNCC first gained public notice in Alabama during the May 1961 Freedom Rides, which were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as a two-week journey through the South to test the implementation of a December 1960 U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation of interstate bus passengers in terminal restrooms, waiting rooms, and restaurants. During the rides, which began on May 4, 1961, riders on the two buses (including John Lewis) were attacked and beaten when they arrived in Anniston, Birmingham, and Montgomery.

Attack on Freedom Riders in Anniston

SNCC first gained public notice in Alabama during the May 1961 Freedom Rides, which were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as a two-week journey through the South to test the implementation of a December 1960 U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation of interstate bus passengers in terminal restrooms, waiting rooms, and restaurants. During the rides, which began on May 4, 1961, riders on the two buses (including John Lewis) were attacked and beaten when they arrived in Anniston, Birmingham, and Montgomery.

Having seen the need for change in Alabama firsthand during the Freedom Rides, SNCC leaders began looking seriously into organizing a voter-registration campaign in the state in late 1962. Bernard and Colia Liddell Lafayette moved to Selma from Mississippi, where they had been working with SNCC, in February 1963 in order to register black voters and help develop local leadership. In Selma, the Lafayettes often worked with the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL). The efforts of the Lafayettes in Alabama were similar to those of existing SNCC projects in Mississippi and Georgia, focusing on strengthening grassroots leadership and increasing African American participation in the political system. Another important component of SNCC’s work was the establishment of literacy programs, and one was established in Selma later in 1963 under the direction of Mary Varela. SNCC also initiated projects elsewhere in Dallas County, as well as in Wilcox County, Gadsden, and other areas. Through mass meetings, voter-education workshops, literacy programs, and direct help to people wishing to register, the Lafayettes, and later SNCC Alabama project directors Worth Long, John Love, and Silas Norman, made inroads into cracking Alabama’s wall of segregation.

In the spring of 1963, Birmingham’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), headed by Fred Shuttlesworth, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) joined with local Birmingham residents in a mass campaign against segregation. Although SNCC’s activities were focused elsewhere at the time (primarily in Mississippi, Georgia, and Maryland), SNCC individuals played supporting roles in this movement. Diane Nash, one of the main people behind SNCC’s continuation of the Freedom Rides despite the violence in Alabama, came to Birmingham with her husband, James Bevel, and worked to mobilize children and high school students for the demonstrations. Another such person was SNCC Executive Secretary James Forman, who also worked with Birmingham youth, spoke at mass meetings, and helped plan some of the demonstrations, but tensions between SCLC and SNCC about who was heading the campaign and how it should be undertaken soon derailed his involvement. Nevertheless, in many of the other communities in which SNCC was working around the South, SNCC organizers often held mass meetings and demonstrations in support of the Birmingham protests.

On August 28, 1963, John Lewis participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, coordinated by A. Philip Randolph, a long-time civil rights and labor activist and the founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and Bayard Rustin, another activist with decades of experience in the civil rights and pacifist movements. For months before the march, members of SNCC (including John Lewis), the SCLC (headed by Martin Luther King Jr.), CORE, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League, the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), and other civil, labor, and religious organizations, convened to organize the mass demonstration. On the day of the march, before the thousands gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial and a global television and radio audience, Lewis gave a speech in which he criticized the Kennedy administration and the limited scope of the Civil Rights Bill under discussion in Congress (what became the Civil Rights Act of 1964). Lewis also discussed the role of economic inequities in the civil rights struggle and linked the U.S. movement to the fight for freedom and independence in decolonizing Africa.

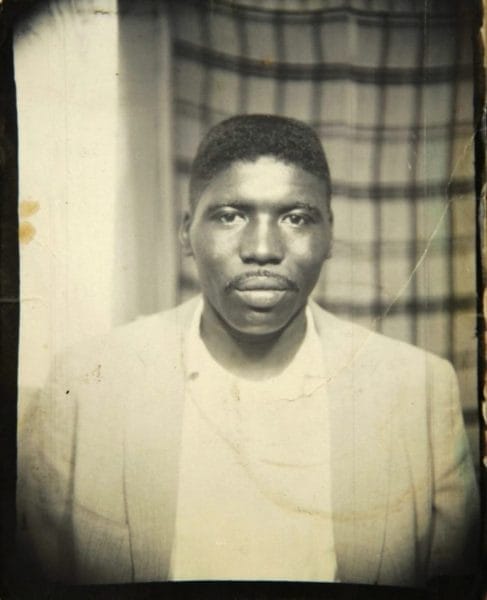

Jimmie Lee Jackson

While events such as the Birmingham campaign and the March on Washington gained national attention, SNCC continued its work on the ground in Alabama. In the late fall of 1964, the DCVL and the SCLC began to plan a voting-rights campaign for Selma, supplementing the work that SNCC was already doing. The groups organized a series of nonviolent demonstrations that commenced in January and were met with strong white resistance. On February 18, 1965, civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot by a state trooper during a protest in Marion; he died on February 26. SCLC activists, angered over another murder in the fight for civil rights, called for a march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery to force the government to ensure voting rights. Despite some reservations over SCLC’s strategies (SNCC felt that the SCLC placed too much emphasis on going into communities, taking over for big events, and then leaving, rather than developing local, grassroots leadership and organizations that could then sustain themselves) SNCC provided logistical support such as the use of its Wide Area Telephone Service (WATS) lines and the services of the Medical Committee on Human Rights, organized by SNCC during the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964. Additionally, several SNCC individuals, including chair John Lewis (who had been actively involved in the earlier Selma protests), participated in the initial march, and several others soon joined in. On March 7, hundreds of marchers, led by Lewis and SCLC’s Hosea Williams, set off through Selma and across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where they encountered a blockade of local police and state troopers under orders from Gov. George Wallace to halt the protest. When the marchers refused to stop, they were beaten and tear-gassed during what became known as Bloody Sunday.

Jimmie Lee Jackson

While events such as the Birmingham campaign and the March on Washington gained national attention, SNCC continued its work on the ground in Alabama. In the late fall of 1964, the DCVL and the SCLC began to plan a voting-rights campaign for Selma, supplementing the work that SNCC was already doing. The groups organized a series of nonviolent demonstrations that commenced in January and were met with strong white resistance. On February 18, 1965, civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot by a state trooper during a protest in Marion; he died on February 26. SCLC activists, angered over another murder in the fight for civil rights, called for a march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery to force the government to ensure voting rights. Despite some reservations over SCLC’s strategies (SNCC felt that the SCLC placed too much emphasis on going into communities, taking over for big events, and then leaving, rather than developing local, grassroots leadership and organizations that could then sustain themselves) SNCC provided logistical support such as the use of its Wide Area Telephone Service (WATS) lines and the services of the Medical Committee on Human Rights, organized by SNCC during the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964. Additionally, several SNCC individuals, including chair John Lewis (who had been actively involved in the earlier Selma protests), participated in the initial march, and several others soon joined in. On March 7, hundreds of marchers, led by Lewis and SCLC’s Hosea Williams, set off through Selma and across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where they encountered a blockade of local police and state troopers under orders from Gov. George Wallace to halt the protest. When the marchers refused to stop, they were beaten and tear-gassed during what became known as Bloody Sunday.

SNCC organizers and other civil rights activists called for an injunction against Wallace’s interference, but U.S. District Court judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. issued a restraining order against the march until a hearing could decide the issue. Despite the injunction, SNCC organizers were among the thousands of participants from around the country who again approached the bridge on March 9. When Martin Luther King Jr. led the marchers in prayer and then asked them to turn around—part of a behind-the-scenes agreement with federal officials—SNCC activists were angered at what they saw as a capitulation, believing that the marchers should have continued. After days of demonstrations, Judge Johnson finally authorized the march. On March 21, an even larger crowd of some 8,000 protestors, including numerous SNCC organizers, started a five-day walk with federal protection, culminating in a rally of some 25,000 people in front of the state capitol.

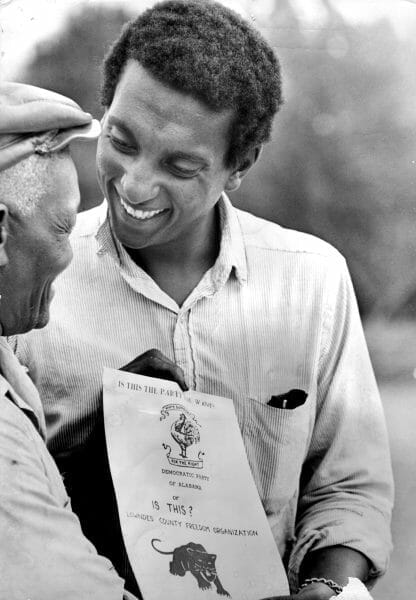

Stokely Carmichael

As SNCC workers marched through Lowndes County, located between Selma and Montgomery, they encountered an area of extreme poverty and racial inequality. Although the county’s population was approximately 80 percent African American, only a miniscule number of blacks were registered to vote, and the white minority held virtually all political and economic power. Within a month of the march, SNCC organizer Stokely Carmichael moved to the county to begin a voter-registration campaign, and he was quickly joined by other SNCC members. The volunteers first focused on registering black voters, but by the end of the summer and with the passage of the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965, SNCC members and local activists changed their focus and formed a new independent political party, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), symbolized by a black panther. In addition to registering voters and explaining the political process, the LCFO, or Black Panther Party, also ran its own slate of candidates on a Black Power platform in county elections. In October 1966, activists Huey Newton and Bobby Seale used the LCFO’s nickname and image when they founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California, which soon became national in scope.

Stokely Carmichael

As SNCC workers marched through Lowndes County, located between Selma and Montgomery, they encountered an area of extreme poverty and racial inequality. Although the county’s population was approximately 80 percent African American, only a miniscule number of blacks were registered to vote, and the white minority held virtually all political and economic power. Within a month of the march, SNCC organizer Stokely Carmichael moved to the county to begin a voter-registration campaign, and he was quickly joined by other SNCC members. The volunteers first focused on registering black voters, but by the end of the summer and with the passage of the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965, SNCC members and local activists changed their focus and formed a new independent political party, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), symbolized by a black panther. In addition to registering voters and explaining the political process, the LCFO, or Black Panther Party, also ran its own slate of candidates on a Black Power platform in county elections. In October 1966, activists Huey Newton and Bobby Seale used the LCFO’s nickname and image when they founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California, which soon became national in scope.

Another important event in the SNCC-Alabama relationship was the January 3, 1966, murder of Sammy Younge Jr., a military veteran, in Tuskegee. For some time, SNCC and a group of students in the Tuskegee Institute Advancement League (TIAL) had been working together, registering voters and challenging segregation, and Younge was part of this coalition. Killed while trying to use a white-only restroom at a local gas station, Younge’s murder was used three days in SNCC’s first public statement against U.S. involvement in the war in Vietnam. Highlighting the similarities between the Vietnamese struggle for independence and black Americans’ fight for their rights, personified by the murder of Younge and the killing of Vietnamese peasants, SNCC called out the U.S. government for failing to uphold both national and international law.

SNCC’s efforts in Alabama throughout the 1960s reflected many of the main strategies of the organization, including nonviolent demonstrations, grassroots organizing, voter registration campaigns, and the promotion of Black Power. Just as Alabamians played central roles in the organization, SNCC’s work left lasting imprints on the state.

Further Reading

- Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. 2nd ed. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Halberstam, David. The Children. New York: Ballantine, 1998.

- Lewis, John, with Michael D’Orso. Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1998.

- Zellner, Bob, with Constance Curry. The Wrong Side of Murder Creek: A White Southerner in the Freedom Movement. Montgomery, Ala.: NewSouth Books, 2008.