University of Alabama at Birmingham

UAB’s Heritage Hall

The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) is an autonomous, state-supported institution of higher learning located in downtown Birmingham. By 1976, UAB was Birmingham’s largest employer, and it acted as an economic force that helped change the city’s economic base from heavy industry to professional services. Established in 1966, UAB currently serves more than 22,000 undergraduate, graduate, and professional students from every county in Alabama, as well as other states in the nation and from more than 110 countries. Approximately 60 percent of the student body is female, and approximately 35 percent are minorities. UAB offers 155 degrees and certificates in 12 different schools. It had a workforce of 18,765 as of 2006. Nearly 53,000 people work for the institution itself as well as in the UAB Health System.

UAB’s Heritage Hall

The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) is an autonomous, state-supported institution of higher learning located in downtown Birmingham. By 1976, UAB was Birmingham’s largest employer, and it acted as an economic force that helped change the city’s economic base from heavy industry to professional services. Established in 1966, UAB currently serves more than 22,000 undergraduate, graduate, and professional students from every county in Alabama, as well as other states in the nation and from more than 110 countries. Approximately 60 percent of the student body is female, and approximately 35 percent are minorities. UAB offers 155 degrees and certificates in 12 different schools. It had a workforce of 18,765 as of 2006. Nearly 53,000 people work for the institution itself as well as in the UAB Health System.

Largely because of its stature in the healthcare field, the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education classifies UAB as a highly ranked research university, the only institution of higher learning in Alabama so designated. This classification is used by foundations, governments, and other institutions to grant money for scholarly and medical research. In 2006, U.S. News and World Report ranked five programs within the UAB School of Medicine in the top 20 in graduate education: AIDS research, geriatrics, internal medicine, pediatrics, and women’s health. UAB ranked 27th in research and 34th in primary care among the nation’s medical schools and teaching and research hospitals. The UAB Health System is independent of UAB’s academic unit, but it is closely associated with UAB’s hospitals and clinics and its various health schools.

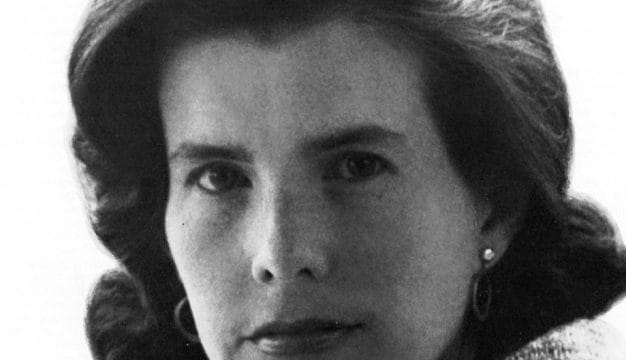

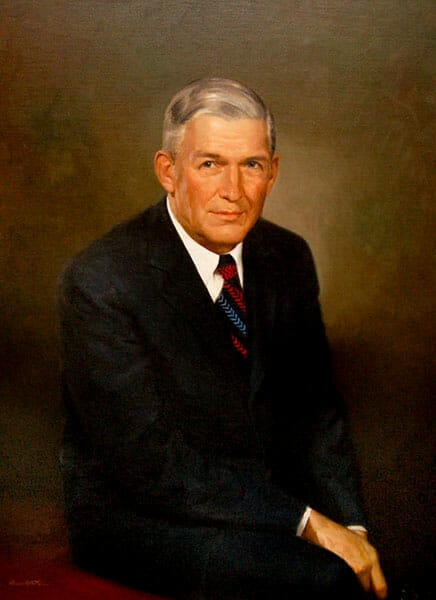

Joseph Volker

In its early years, UAB was a loosely connected group of health and academic schools, largely referred to separately as the University of Alabama Medical Center and Extension Center, until they were organized as a branch campus within the University of Alabama (UA) in 1966. It became an autonomous institution three years later. Dentist Joseph F. Volker was its first president, serving from 1969 until he became Chancellor of the University of Alabama System in 1976. Physician S. Richardson Hill took over as UAB’s president in 1977, and Charles A. McCallum, a physician and dentist, succeeded him in 1987. In 1993, physician J. Claude Bennett became president, and four years later, zoologist Ann W. Reynolds became the first woman to serve as UAB’s president, until 2002. Epidemiologist Carol Z. Garrison served as president until 2013, when she was replaced by physician Ray L. Watts.

Joseph Volker

In its early years, UAB was a loosely connected group of health and academic schools, largely referred to separately as the University of Alabama Medical Center and Extension Center, until they were organized as a branch campus within the University of Alabama (UA) in 1966. It became an autonomous institution three years later. Dentist Joseph F. Volker was its first president, serving from 1969 until he became Chancellor of the University of Alabama System in 1976. Physician S. Richardson Hill took over as UAB’s president in 1977, and Charles A. McCallum, a physician and dentist, succeeded him in 1987. In 1993, physician J. Claude Bennett became president, and four years later, zoologist Ann W. Reynolds became the first woman to serve as UAB’s president, until 2002. Epidemiologist Carol Z. Garrison served as president until 2013, when she was replaced by physician Ray L. Watts.

Health Education

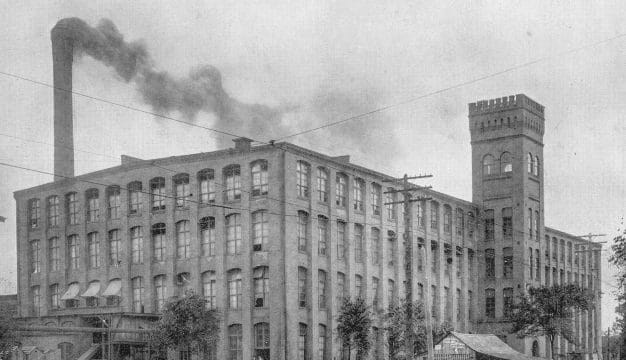

Hillman Hospital

UAB’s reputation derives largely from its world-renowned medical center. UAB’s health program began in 1944, when the Medical College of Alabama relocated from Tuscaloosa to Birmingham. The college, overseen by the UA board of trustees, had folded in 1920 and its two-year basic science program was relocated to Tuscaloosa from Mobile shortly thereafter. For more than 20 years, the state of Alabama was without a medical school and suffered a severe shortage of healthcare professionals. In 1943, the Alabama legislature passed the Jones Act, which appropriated $1.3 million to rebuild, maintain, and equip a new medical college. Gov. Chauncey Sparks (1943-1947) appointed the Governor’s Building Commission, which considered Birmingham (the state’s largest city), Mobile (the original location), Montgomery (the state capital), and Tuscaloosa (the home of the University of Alabama) for the college’s location. Birmingham was selected in part because Jefferson County offered a large and diverse potential patient population. The city deeded Hillman and Jefferson Hospitals to the university, and local citizens raised $160,000 for the college to acquire additional land. In 1945, the state legislature created the School of Dentistry.

Hillman Hospital

UAB’s reputation derives largely from its world-renowned medical center. UAB’s health program began in 1944, when the Medical College of Alabama relocated from Tuscaloosa to Birmingham. The college, overseen by the UA board of trustees, had folded in 1920 and its two-year basic science program was relocated to Tuscaloosa from Mobile shortly thereafter. For more than 20 years, the state of Alabama was without a medical school and suffered a severe shortage of healthcare professionals. In 1943, the Alabama legislature passed the Jones Act, which appropriated $1.3 million to rebuild, maintain, and equip a new medical college. Gov. Chauncey Sparks (1943-1947) appointed the Governor’s Building Commission, which considered Birmingham (the state’s largest city), Mobile (the original location), Montgomery (the state capital), and Tuscaloosa (the home of the University of Alabama) for the college’s location. Birmingham was selected in part because Jefferson County offered a large and diverse potential patient population. The city deeded Hillman and Jefferson Hospitals to the university, and local citizens raised $160,000 for the college to acquire additional land. In 1945, the state legislature created the School of Dentistry.

The UA board of trustees named Roy R. Kracke, a pioneer in clinical pathology, as the dean of the Medical College and Joseph F. Volker as dean of the School of Dentistry in 1944 and 1948, respectively. The two men worked to create a world-class medical center akin to the University of Chicago’s Rush Medical Center, but they soon found that they needed additional land and funding to make that happen. Krake died in 1950 before he could realize his goal of establishing a leading medical facility in Birmingham.

UAB Hospital

Volker pushed on with their vision by pursuing federal funding as director of Graduate and Research Studies. He took advantage of New Deal programs in Alabama by seeking federal funding through the Hill-Burton Hospital Construction and Survey Act of 1946, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Housing Act of 1949. Alabama senators and New Deal progressives Lister Hill and John Sparkman aided Volker by continually altering legislation to meet the needs of the medical center. The Hill-Burton Act and the NIH supported hospital construction and medical research; by 1968 the federal government was providing 36 percent of UAB’s total funding. Sparkman’s support for the Housing Act and its subsequent incarnations aided urban development across the natoin by supporting urban renewal measures. The Medical Center used urban renewal initiatives to acquire additional land in 1957 and in 1968. UAB’s expansion, based on federal funding and urban renewal, allowed Volker to fulfill his vision of a world-class medical center and urban university.

UAB Hospital

Volker pushed on with their vision by pursuing federal funding as director of Graduate and Research Studies. He took advantage of New Deal programs in Alabama by seeking federal funding through the Hill-Burton Hospital Construction and Survey Act of 1946, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Housing Act of 1949. Alabama senators and New Deal progressives Lister Hill and John Sparkman aided Volker by continually altering legislation to meet the needs of the medical center. The Hill-Burton Act and the NIH supported hospital construction and medical research; by 1968 the federal government was providing 36 percent of UAB’s total funding. Sparkman’s support for the Housing Act and its subsequent incarnations aided urban development across the natoin by supporting urban renewal measures. The Medical Center used urban renewal initiatives to acquire additional land in 1957 and in 1968. UAB’s expansion, based on federal funding and urban renewal, allowed Volker to fulfill his vision of a world-class medical center and urban university.

Academic Programs

UAB’s academic program has its roots in Depression-era Birmingham. In 1936, UA established the Extension Center in the city’s central business district to serve the adult white population by providing business, education, and engineering instruction. Enrollment was steady if small until the medical college relocated to Birmingham in 1944. The Extension Center housed the two-year basic science program to meet the educational needs of the college’s medical and dental students. The student body expanded after that move because of Birmingham’s population growth during and after World War II and the many veterans using their GI Bill benefits to obtain a higher education. To bring greater unity to its Birmingham operations, the UA board of trustees moved the Extension Center near the medical college in the city’s Southside neighborhood.

Alys Stephens Performing Arts Center

Local demands continued to influence the center’s growth. In 1950, a school of nursing was established at UA in Tuscaloosa, which was moved to Birmingham and the UAB system in 1967. In the mid-1950s, the Birmingham Little Theater was donated to the Center, sparking the development of a theater department a few years later. In 1961, the UA board of trustees approved the creation of an engineering program; it was the first nonmedical four-year program in Birmingham and was established in 1962 and reorganized in 1971 as the School of Engineering. The program was created to satisfy local engineers and businessmen who wanted to further their education and professional development. The Extension Center’s enrollment growth and the diversity of its programs prompted the UA board of trustees to organize the College of General Studies to give greater cohesion to the nonmedical programs; two months later, in November 1966, the trustees declared all of its Birmingham operations as the University of Alabama in Birmingham, a branch campus of the University of Alabama System. With the establishment of UAB as an autonomous campus in 1969, Birmingham finally acquired a public institution of higher learning to meet the educational needs of both its white and black citizens. Racial integration within the academic side of UAB came quite rapidly. The first African American student, Luther Lawler, enrolled in the fall of 1963, and by 1970, 10 percent of the student body of UAB was African American.

Alys Stephens Performing Arts Center

Local demands continued to influence the center’s growth. In 1950, a school of nursing was established at UA in Tuscaloosa, which was moved to Birmingham and the UAB system in 1967. In the mid-1950s, the Birmingham Little Theater was donated to the Center, sparking the development of a theater department a few years later. In 1961, the UA board of trustees approved the creation of an engineering program; it was the first nonmedical four-year program in Birmingham and was established in 1962 and reorganized in 1971 as the School of Engineering. The program was created to satisfy local engineers and businessmen who wanted to further their education and professional development. The Extension Center’s enrollment growth and the diversity of its programs prompted the UA board of trustees to organize the College of General Studies to give greater cohesion to the nonmedical programs; two months later, in November 1966, the trustees declared all of its Birmingham operations as the University of Alabama in Birmingham, a branch campus of the University of Alabama System. With the establishment of UAB as an autonomous campus in 1969, Birmingham finally acquired a public institution of higher learning to meet the educational needs of both its white and black citizens. Racial integration within the academic side of UAB came quite rapidly. The first African American student, Luther Lawler, enrolled in the fall of 1963, and by 1970, 10 percent of the student body of UAB was African American.

Rosette Bobbin on UAB Campus

The UA Board of Trustees reorganized the College of General Studies into University College in 1971; it consisted of the schools of Arts and Sciences, Business, Education, and Engineering. In 1989, University College became UAB Academic Affairs, with eight different schools: Arts and Humanities, Business, Engineering, Education, Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Social and Behavioral Sciences, Division of General Studies, and the Graduate School. In 1984, the UA Board changed UAB’s name to the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In 2010, UAB combined the schools of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Social and Behavioral Sciences, and Arts and Humanities into the College of Arts and Sciences; the School of Education also is affiliated with this division but retains its status as a separate school.

Rosette Bobbin on UAB Campus

The UA Board of Trustees reorganized the College of General Studies into University College in 1971; it consisted of the schools of Arts and Sciences, Business, Education, and Engineering. In 1989, University College became UAB Academic Affairs, with eight different schools: Arts and Humanities, Business, Engineering, Education, Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Social and Behavioral Sciences, Division of General Studies, and the Graduate School. In 1984, the UA Board changed UAB’s name to the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In 2010, UAB combined the schools of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Social and Behavioral Sciences, and Arts and Humanities into the College of Arts and Sciences; the School of Education also is affiliated with this division but retains its status as a separate school.

Blaze the Dragon

In 1977, UAB added an athletics department. President Hill attracted Gene Bartow, who coached at the University of California, Los Angeles, for two years, to lead UAB’s new athletic program and collegiate basketball program. Bartow coached the UAB Blazers in the NCAA tournament seven times. In 1991, President McCallum announced plans to develop a football program; three years later, UAB’s football program advanced to the NCAA I-A division. In 2014, UAB announced that it would discontinue its football program, citing dramatically rising costs. After a large public outcry and a fundraiser that brought in $27 million dollars to the program, the university administration reversed its decision in June 2015. The UAB mascot, Blaze the Dragon, first appeared at college athletic games in 1995; its early incarnations were a pink dragon (1978) and Beauregard T. Rooster (1979). UAB’s school colors are gold and green.

Blaze the Dragon

In 1977, UAB added an athletics department. President Hill attracted Gene Bartow, who coached at the University of California, Los Angeles, for two years, to lead UAB’s new athletic program and collegiate basketball program. Bartow coached the UAB Blazers in the NCAA tournament seven times. In 1991, President McCallum announced plans to develop a football program; three years later, UAB’s football program advanced to the NCAA I-A division. In 2014, UAB announced that it would discontinue its football program, citing dramatically rising costs. After a large public outcry and a fundraiser that brought in $27 million dollars to the program, the university administration reversed its decision in June 2015. The UAB mascot, Blaze the Dragon, first appeared at college athletic games in 1995; its early incarnations were a pink dragon (1978) and Beauregard T. Rooster (1979). UAB’s school colors are gold and green.

Further Reading

- McWilliams, Tennant S. New Lights in the Valley: The Emergence of UAB. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

- Scribner, Christopher MacGregor. Renewing Birmingham: Federal Funding and the Promise of Change, 1929-1979. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002.