Cultural Geography of Alabama

Cotton Mill Workers

Since achieving statehood in 1819, Alabama and its counties and municipalities have undergone numerous demographic changes. Waves of white settlers rushed into the state during the early years to acquire the best land for growing cotton. After the Civil War and Emancipation, formerly enslaved African Americans fled in large numbers to urban areas in search of industrial jobs and later to other states during the Great Migration. Rural white and black Alabamians flocked to the state’s major cities in search of industrial jobs during the war years and more recently headed to the expanding suburbs. Throughout this time, the state and its residents have experienced periods of poverty and prosperity that followed the rise and fall of agriculture and industry.

Cotton Mill Workers

Since achieving statehood in 1819, Alabama and its counties and municipalities have undergone numerous demographic changes. Waves of white settlers rushed into the state during the early years to acquire the best land for growing cotton. After the Civil War and Emancipation, formerly enslaved African Americans fled in large numbers to urban areas in search of industrial jobs and later to other states during the Great Migration. Rural white and black Alabamians flocked to the state’s major cities in search of industrial jobs during the war years and more recently headed to the expanding suburbs. Throughout this time, the state and its residents have experienced periods of poverty and prosperity that followed the rise and fall of agriculture and industry.

Two Cultural Regions

Folk geographers, specialists who study spatial patterns and the cultural ecology of folklife, have traditionally divided Alabama into two cultural regions: the Midland Traditional Culture Region, which covers the northern portion of the state from just above the Blackland Prairie to the Tennessee border, and the Lower South Traditional Culture Region, which includes the remainder of the state.

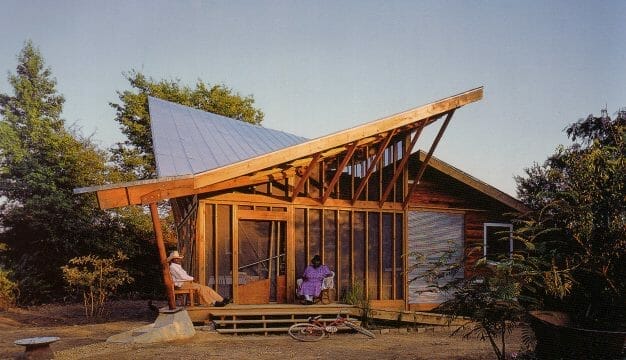

Dogtrot Cabin at Belle Mont Plantation

The Midland and Lower South culture regions can be defined roughly by their specific varieties of speech pattern, called isoglosses, which are determined by word usage and pronunciation. Linguistic distinctions are more easily recognized in the vocabulary of “folk” speech patterns. Some linguists have identified two dialect regions, the Midland and the Southern, in Alabama, whereas others have divided the state into the Upper South and Lower South dialect regions. It is difficult at best to draw clear boundaries between dialect speakers, and language is constantly changing, but regional linguistic variations persist in rural areas and among the elderly. For example, in rural sections of southern and central Alabama, the common folk term for dragonfly is “mosquito hawk” or “skeeter hawk.” In northern portions of the state, however, the insect is referred to as a “snake doctor” or “snake feeder.” Midland dialect speakers are often divided according to northern versus southern pronunciation of words as well. In Northern and Midland dialects, for example, the second vowel in the word admire is sounded as a diphthong, a vowel that requires movement of the tongue to sound, (ədm-ay-r), but it is pronounced ədm-a-r in the lower south culture region.

Dogtrot Cabin at Belle Mont Plantation

The Midland and Lower South culture regions can be defined roughly by their specific varieties of speech pattern, called isoglosses, which are determined by word usage and pronunciation. Linguistic distinctions are more easily recognized in the vocabulary of “folk” speech patterns. Some linguists have identified two dialect regions, the Midland and the Southern, in Alabama, whereas others have divided the state into the Upper South and Lower South dialect regions. It is difficult at best to draw clear boundaries between dialect speakers, and language is constantly changing, but regional linguistic variations persist in rural areas and among the elderly. For example, in rural sections of southern and central Alabama, the common folk term for dragonfly is “mosquito hawk” or “skeeter hawk.” In northern portions of the state, however, the insect is referred to as a “snake doctor” or “snake feeder.” Midland dialect speakers are often divided according to northern versus southern pronunciation of words as well. In Northern and Midland dialects, for example, the second vowel in the word admire is sounded as a diphthong, a vowel that requires movement of the tongue to sound, (ədm-ay-r), but it is pronounced ədm-a-r in the lower south culture region.

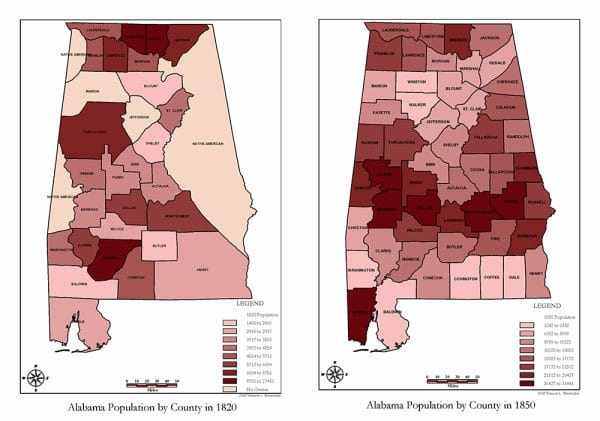

Alabama Population Growth

Traditionally, the Midland region was occupied by settlers from a wide variety of ethnic backgrounds, including English, Scots-Irish, German, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, Welsh, and other European groups who brought with them diverse religions and agricultural experiences. Throughout the early and mid-nineteenth century, these settlers established the state’s many middle-class family farms. The populace of the Lower South combined elements of British, French, Caribbean, and African cultures in a plantation system characterized by large-scale cotton cultivation on extensive parcels under absentee ownership with a heavy reliance on enslaved labor. Historical censuses for the period from 1820 to 1860 indicate that several northern Alabama counties—including Madison, Lawrence, Limestone, and Franklin—had significant percentages of African slaves as well. However, by the mid-twentieth century these counties no longer ranked among the top by percent of population of African Americans. Indeed, Franklin had dropped to below 10 percent.

Alabama Population Growth

Traditionally, the Midland region was occupied by settlers from a wide variety of ethnic backgrounds, including English, Scots-Irish, German, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, Welsh, and other European groups who brought with them diverse religions and agricultural experiences. Throughout the early and mid-nineteenth century, these settlers established the state’s many middle-class family farms. The populace of the Lower South combined elements of British, French, Caribbean, and African cultures in a plantation system characterized by large-scale cotton cultivation on extensive parcels under absentee ownership with a heavy reliance on enslaved labor. Historical censuses for the period from 1820 to 1860 indicate that several northern Alabama counties—including Madison, Lawrence, Limestone, and Franklin—had significant percentages of African slaves as well. However, by the mid-twentieth century these counties no longer ranked among the top by percent of population of African Americans. Indeed, Franklin had dropped to below 10 percent.

Early Settlement and the Civil War Era

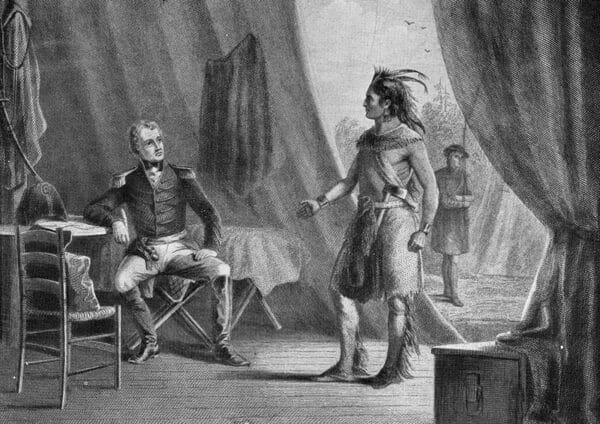

Treaty of Fort Jackson

Alabama has long had a strong rural tradition based on farming. Prior to the nineteenth century, the territory that would ultimately become the state of Alabama was divided among four Native American nations: the Cherokees, Creeks, Chickasaws, and Choctaws. Cherokee territory covered a large portion of modern-day northeastern Alabama, the Chickasaws claimed land in the northwest, and Choctaw lands were located to the west and southwest. The Creeks occupied the largest portion of land, totaling more than two-thirds of the territory that was to become Alabama. These peoples hunted, fished, and grew a variety of food plants, including beans, squash, melons, pumpkins, and corn, along Alabama’s major rivers and tributaries, where fertile soils could be found and wildlife was bountiful. After (and sometimes even before) the Indian nations ceded their traditional territories to the U.S. government and were relocated to what is now Oklahoma, white settlers established homesteads and towns on the land. The most attractive properties, flat bottom lands with goods soils and access to navigable rivers or highways, were settled first.

Treaty of Fort Jackson

Alabama has long had a strong rural tradition based on farming. Prior to the nineteenth century, the territory that would ultimately become the state of Alabama was divided among four Native American nations: the Cherokees, Creeks, Chickasaws, and Choctaws. Cherokee territory covered a large portion of modern-day northeastern Alabama, the Chickasaws claimed land in the northwest, and Choctaw lands were located to the west and southwest. The Creeks occupied the largest portion of land, totaling more than two-thirds of the territory that was to become Alabama. These peoples hunted, fished, and grew a variety of food plants, including beans, squash, melons, pumpkins, and corn, along Alabama’s major rivers and tributaries, where fertile soils could be found and wildlife was bountiful. After (and sometimes even before) the Indian nations ceded their traditional territories to the U.S. government and were relocated to what is now Oklahoma, white settlers established homesteads and towns on the land. The most attractive properties, flat bottom lands with goods soils and access to navigable rivers or highways, were settled first.

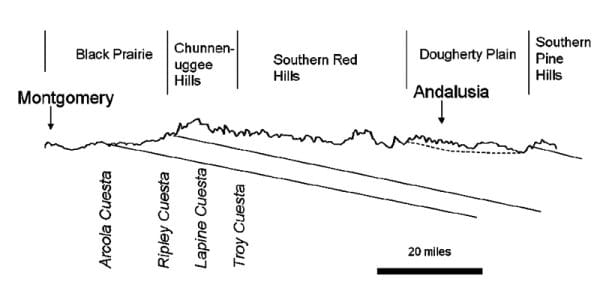

East Gulf Coastal Plain Cross-section

Initially, settlers followed improved roads and wagon trails into the state, establishing their homes on the fertile flatlands, river valleys, and flood plains and along tributaries. Many of the early settlers were yeoman farmers who occupied unsurveyed public lands in the hopes of gaining title to the land when the parcels came to market. Between 1820 and 1850, Alabama’s documented population grew from 144,317 persons living in 27 counties to 771,623 people in 52 counties. The new Alabamians subsisted on corn and local plants and animals. Many settlers were so poor that they were forced to rely on what they could gather from the wilderness until their farm plots were established. Wealthy cotton farmers from states to the east and north and their sons and families abandoned spent farmlands for the fertile soils of Alabama, bringing with them African slaves to clear and work the land. The planters favored the broad flat parcels of land in the Tennessee Valley and Coastal Plain, and they purchased large tracts for the purpose of raising cash crops for the market. The unique physical geography of central and southern Alabama, in particular its dark rich soils, made the Blackland Prairie (or Black Belt, as it is popularly known) ideal for raising cotton. Seventeen Alabama counties are considered to be part of the traditional Black Belt. Although difficult to plow, the soils of the Black Belt were well-suited to the cultivation of wheat, cotton, and rice. In the decades after the war, a substantial portion of the cotton raised in Alabama was harvested from Black Belt fields. North of the Blackland Prairie in the Tennessee Valley, many planters opted for more diverse crops, cultivating grains and hay alongside cotton. Like Black Belt farmers, growers in the hill country and southern counties preferred cotton.

East Gulf Coastal Plain Cross-section

Initially, settlers followed improved roads and wagon trails into the state, establishing their homes on the fertile flatlands, river valleys, and flood plains and along tributaries. Many of the early settlers were yeoman farmers who occupied unsurveyed public lands in the hopes of gaining title to the land when the parcels came to market. Between 1820 and 1850, Alabama’s documented population grew from 144,317 persons living in 27 counties to 771,623 people in 52 counties. The new Alabamians subsisted on corn and local plants and animals. Many settlers were so poor that they were forced to rely on what they could gather from the wilderness until their farm plots were established. Wealthy cotton farmers from states to the east and north and their sons and families abandoned spent farmlands for the fertile soils of Alabama, bringing with them African slaves to clear and work the land. The planters favored the broad flat parcels of land in the Tennessee Valley and Coastal Plain, and they purchased large tracts for the purpose of raising cash crops for the market. The unique physical geography of central and southern Alabama, in particular its dark rich soils, made the Blackland Prairie (or Black Belt, as it is popularly known) ideal for raising cotton. Seventeen Alabama counties are considered to be part of the traditional Black Belt. Although difficult to plow, the soils of the Black Belt were well-suited to the cultivation of wheat, cotton, and rice. In the decades after the war, a substantial portion of the cotton raised in Alabama was harvested from Black Belt fields. North of the Blackland Prairie in the Tennessee Valley, many planters opted for more diverse crops, cultivating grains and hay alongside cotton. Like Black Belt farmers, growers in the hill country and southern counties preferred cotton.

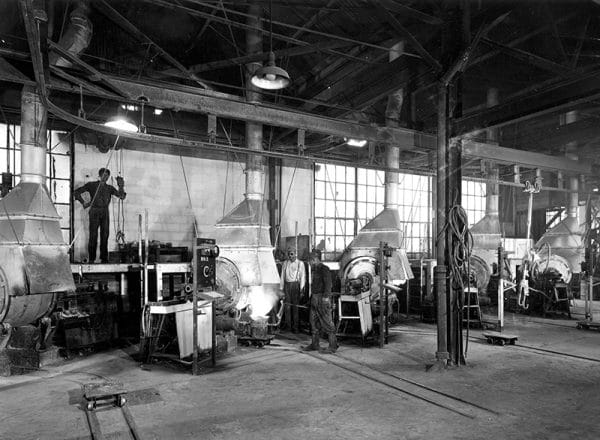

Stockham Electric Furnaces

With the decline of the plantation agriculture system following the end of the Civil War, Alabama’s Black Belt gradually evolved from one of the wealthiest areas of the state to one of the poorest, and it remains so today. When slavery ended, many African American residents of the region—as well as a number of poor whites—found themselves enmeshed in another repressive system based on the economics of tenant farming. Many more toiled in the coal mines and iron mills of north Alabama or the textile mills of the rural central and southern counties. Exploitation of vast coal reserves in northern Alabama fueled the growth of the iron and steel industry, which flourished into the twentieth century. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, many rural Alabamians, including a significant number of African Americans, migrated to northern cities in search of employment opportunities. Today, Black Belt counties experience lagging or no economic growth, poverty, unemployment, out-migration, low educational achievement, insufficient educational opportunities, a high incidence of births to unwed mothers, and a significant number of single-parent families. Furthermore, a substantial amount of the property in Alabama’s Black Belt is now owned by corporations or individuals who do not reside on the land. Today, governmental agencies and taskforces as well as a variety of non-governmental organizations are attempting to improve the quality of life in Alabama’s once-thriving Black Belt.

Stockham Electric Furnaces

With the decline of the plantation agriculture system following the end of the Civil War, Alabama’s Black Belt gradually evolved from one of the wealthiest areas of the state to one of the poorest, and it remains so today. When slavery ended, many African American residents of the region—as well as a number of poor whites—found themselves enmeshed in another repressive system based on the economics of tenant farming. Many more toiled in the coal mines and iron mills of north Alabama or the textile mills of the rural central and southern counties. Exploitation of vast coal reserves in northern Alabama fueled the growth of the iron and steel industry, which flourished into the twentieth century. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, many rural Alabamians, including a significant number of African Americans, migrated to northern cities in search of employment opportunities. Today, Black Belt counties experience lagging or no economic growth, poverty, unemployment, out-migration, low educational achievement, insufficient educational opportunities, a high incidence of births to unwed mothers, and a significant number of single-parent families. Furthermore, a substantial amount of the property in Alabama’s Black Belt is now owned by corporations or individuals who do not reside on the land. Today, governmental agencies and taskforces as well as a variety of non-governmental organizations are attempting to improve the quality of life in Alabama’s once-thriving Black Belt.

Agriculture, Industry, and Service

Agriculture in Alabama was largely dominated by cotton until the boll weevil devastated the state’s crop during the early years of the twentieth century. Subsequent erosion of once-fertile soils, mounting pressure to expand the state’s crop base, and an increase in both demand and prices for food crops brought diversification to Alabama’s agricultural landscape.

Ultimately, devastation in Alabama’s cotton counties brought on by the boll weevil and poor farming practices caused a shift in cotton agriculture from the Black Belt to several northern counties. In the last 50 years, Alabama’s agricultural landscape has undergone sweeping changes. In 1950, there were approximately 200,000 farms. By 2019, the number of reported farms dropped to roughly 38,000. Moreover, even as the number of farms has decreased, the average size of Alabama’s farms has grown larger. In 1940, the average Alabama farm covered 83 acres. By 2017, average farm size grew to 211 acres. While the physical and cultural geography of Alabama supports a variety of agricultural activities, conversion of farmland and pasture to hunting preserves and commercial timbering has been on the rise statewide.

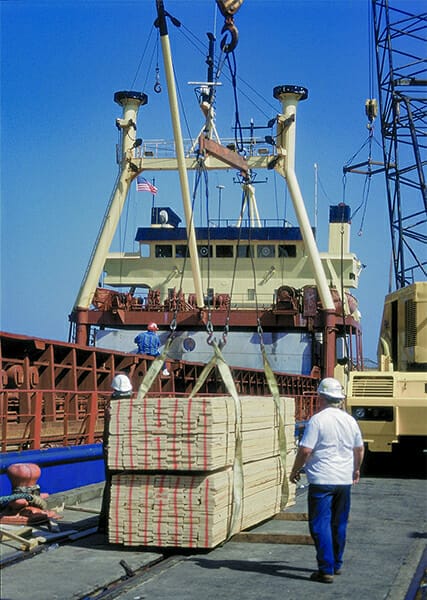

Forest Products at the Port of Mobile

Between 1990 and 2002, approximately one million acres of property were transformed into commercial forest operations, representing a significant economic impact in several rural counties. In 2015, there were approximately 23 million acres of commercial forestland in Alabama that generated a harvest that produced an estimated $16.3 billion in product shipments. Unfortunately, in recent years real growth in the gross domestic product (GDP) in forestry, fishing, and related activities, wood-product manufacturing, and paper manufacturing was about half that for the economy as a whole. Essentially, local communities have been losing their economic diversity even as their residents continue to rely on such diversity for employment. Economic and employment opportunities derived from timber plantations occur in regional centers instead of rural areas. One study suggests that recent efforts to improve efficiency in the timber industry have increased the job losses that have followed modern agricultural transformations. These developments in turn have contributed to increased out-migration. Predictably, the effect of cotton-to-timber conversion on local employment opportunities within rural Alabama counties is less perceptible than the shifting cultural landscape. Vast fields once blanketed in cotton are now fallow or host uniformly planted stands of pine trees.

Forest Products at the Port of Mobile

Between 1990 and 2002, approximately one million acres of property were transformed into commercial forest operations, representing a significant economic impact in several rural counties. In 2015, there were approximately 23 million acres of commercial forestland in Alabama that generated a harvest that produced an estimated $16.3 billion in product shipments. Unfortunately, in recent years real growth in the gross domestic product (GDP) in forestry, fishing, and related activities, wood-product manufacturing, and paper manufacturing was about half that for the economy as a whole. Essentially, local communities have been losing their economic diversity even as their residents continue to rely on such diversity for employment. Economic and employment opportunities derived from timber plantations occur in regional centers instead of rural areas. One study suggests that recent efforts to improve efficiency in the timber industry have increased the job losses that have followed modern agricultural transformations. These developments in turn have contributed to increased out-migration. Predictably, the effect of cotton-to-timber conversion on local employment opportunities within rural Alabama counties is less perceptible than the shifting cultural landscape. Vast fields once blanketed in cotton are now fallow or host uniformly planted stands of pine trees.

In addition to timber, current agricultural operations throughout the state produce cattle, corn, cotton, eggs, poultry, peanuts, pigs, soybeans, wheat, and hay. The geographic distribution of Alabama’s farming generally follows lines of latitude, with cattle, corn, cotton, poultry and eggs, soybeans, and wheat dominate agricultural output in southernmost and northernmost counties; cotton (on a lesser scale), timber, cattle, and hay are found throughout the midsection, including Alabama’s Black Belt; orchard crops and vegetables are raised along the northern limits of the Upper Coastal Plain; and peanut farming is limited to southeastern counties. Today, Alabama’s growers are engaged in several nontraditional farming activities as well. A combination of gentle topography and extensive clay deposits make parts of Alabama’s Black Belt ideal for raising and processing catfish. Modern technology has enabled other farmers to exploit an ancient saline aquifer and raise inland shrimp in the west-central portion of the state.

Gas Rig in the Gulf of Mexico

Alabama’s physical geography influenced industrial development in the state as well. Early on, grist and sawmills were situated along waterways in many counties. The location of coal and iron ore deposits in combination with cotton-based agriculture underpinned a unique geography of iron and textile industries in the state. Iron furnaces were located near hematite deposits in the Alabama Valley and Ridge, Cumberland Plateau, and Highland Rim. Cotton gins and textile mills followed cotton geography dotting the landscape of northern and central Alabama. Additionally, the need to transport harvested cotton and other crops to mills and ports brought about development of the state’s first railway systems.

Gas Rig in the Gulf of Mexico

Alabama’s physical geography influenced industrial development in the state as well. Early on, grist and sawmills were situated along waterways in many counties. The location of coal and iron ore deposits in combination with cotton-based agriculture underpinned a unique geography of iron and textile industries in the state. Iron furnaces were located near hematite deposits in the Alabama Valley and Ridge, Cumberland Plateau, and Highland Rim. Cotton gins and textile mills followed cotton geography dotting the landscape of northern and central Alabama. Additionally, the need to transport harvested cotton and other crops to mills and ports brought about development of the state’s first railway systems.

Today, over and above its agricultural products, Alabama’s modern economy produces a broad range of goods, including paper products, chemicals, textiles, primary metals, food products, clothing, wood products, motor vehicles and parts, and other transportation equipment. The state also supports a growing service and technology industry centered primarily in four major urban centers, Birmingham, Huntsville, Mobile, and Montgomery. In recent years, contributions to Alabama’s GDP from oil and gas extraction, support activities for mining, automotive manufacturing, petroleum and coal products manufacturing, and computer systems design and related services have increased dramatically. The largest growth continues to take place in automotive manufacturing, whereas overall production in computers and electronics, textiles, apparel, paper products, and plastics and rubber declined.

Demographics and Shifting Residential Patterns

Crocheron Columns in Old Cahaba

Like the residents of other largely rural U.S. states, Alabamians have been on the move. High rates of out-migration and population shifts were and remain the consequences of lagging economic growth, poverty, and lack of employment opportunities. The state’s “dead towns” provide a visual record of these changes etched on the cultural landscape. Public records and oral histories suggest that since 1702, 112 colonial towns in Alabama have “died” and are no longer occupied. In 1860, approximately 50 percent of Alabamians resided in 28 of 52 counties. From 1820 to 1870, the 17 counties of Alabama’s traditional Black Belt were the most highly populated in the state. During the Great Migration, which began after the Civil War and continued into the early twentieth century, many black Alabamians abandoned the state to escape racism and take advantage of economic opportunities in the North. By 1910, slightly more than 50 percent resided in 22 of 67 counties, revealing the effect that prosperous counties have had on Alabama’s population movement and centrality, the attraction one place has over others.

Crocheron Columns in Old Cahaba

Like the residents of other largely rural U.S. states, Alabamians have been on the move. High rates of out-migration and population shifts were and remain the consequences of lagging economic growth, poverty, and lack of employment opportunities. The state’s “dead towns” provide a visual record of these changes etched on the cultural landscape. Public records and oral histories suggest that since 1702, 112 colonial towns in Alabama have “died” and are no longer occupied. In 1860, approximately 50 percent of Alabamians resided in 28 of 52 counties. From 1820 to 1870, the 17 counties of Alabama’s traditional Black Belt were the most highly populated in the state. During the Great Migration, which began after the Civil War and continued into the early twentieth century, many black Alabamians abandoned the state to escape racism and take advantage of economic opportunities in the North. By 1910, slightly more than 50 percent resided in 22 of 67 counties, revealing the effect that prosperous counties have had on Alabama’s population movement and centrality, the attraction one place has over others.

From 1910 to the present, Bullock, Butler, Clay, Conecuh, Coosa, Crenshaw, Greene, Hale, Lowndes, Marengo, Perry, Sumter, and Wilcox Counties experienced significant population declines. In 1960, nine counties housed more than 50 percent of the state’s population. By 2000, more than 50 percent of Alabama’s population resided in just nine counties, with Jefferson, Mobile, and Madison counties ranked highest. Census numbers for 2010 indicate little change in population distribution within the state.

The highest growth rates between 1910 and 2015 occurred in counties that encompass its major urban centers, with the exception of Baldwin County, which has attracted residents who seek homes near the coast. The top six growth counties were Limestone, Baldwin, Madison, St. Clair, Shelby, and Houston County. The six counties with the fastest shrinking populations for the same period were Dallas, Lowndes, Wilcox, Choctaw, Conecuh, and Sumter, all in the Black Belt or in the case of Conecuh, bordering it. Recent census data indicate that overall rate of outmigration for Alabama might be declining, suggesting that Alabama’s populace might be shifting rather than leaving the state. Recently, population growth has shifted to Alabama’s rapidly expanding metropolitan areas, which provide access to better health care, employment opportunities, and higher education.

Urban Settlement Patterns

Birmingham

Alabama has few comparatively large urban spaces. The five most populous municipalities in Alabama are Birmingham, Huntsville, Montgomery, Mobile, and Tuscaloosa. According to the Alabama Department of , the state is divided into 13 metropolitan statistical areas (MSA). The Birmingham-Hoover MSA, which includes Blount, Bibb, Chilton, Jefferson, Shelby, St. Clair, and Walker Counties, is Alabama’s largest. According to the most recent Census estimates, the state’s population density averaged 94.4 persons per square mile, 27th in the nation, with a significant majority of the populace residing in the metropolitan statistical areas. Only three southern states—Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas—had lower population densities than Alabama in 2000.

Birmingham

Alabama has few comparatively large urban spaces. The five most populous municipalities in Alabama are Birmingham, Huntsville, Montgomery, Mobile, and Tuscaloosa. According to the Alabama Department of , the state is divided into 13 metropolitan statistical areas (MSA). The Birmingham-Hoover MSA, which includes Blount, Bibb, Chilton, Jefferson, Shelby, St. Clair, and Walker Counties, is Alabama’s largest. According to the most recent Census estimates, the state’s population density averaged 94.4 persons per square mile, 27th in the nation, with a significant majority of the populace residing in the metropolitan statistical areas. Only three southern states—Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas—had lower population densities than Alabama in 2000.

American Sport Art Museum and Archives

Between 2010 and 2018, population declined in three major Alabama cities: Birmingham, Huntsville, and Tuscaloosa. Increasingly, city dwellers have fled urban space for the suburbs, where from 1990 to 2000, equivalent population increases took place in nearby towns. Montgomery’s population increased modestly, but larger increases took place outside the city limits in eastern Montgomery County and in Autauga and Elmore Counties. Mobile’s population remained static, whereas the cities of Daphne and Fairhope in Baldwin County experienced significant growth. Comparisons of population shifts to trends in median household income by county suggest that exurban, residential, and commercial development outside cities and suburbs, driven by migration of middle and upper middle class families, is taking place in rural areas near Alabama’s largest urban spaces. In light of recent trends in “reurbanization,” the pace of migration to the suburbs has started to decline, prompting a heightened emphasis on residential and commercial re-development projects in and around central business districts.

American Sport Art Museum and Archives

Between 2010 and 2018, population declined in three major Alabama cities: Birmingham, Huntsville, and Tuscaloosa. Increasingly, city dwellers have fled urban space for the suburbs, where from 1990 to 2000, equivalent population increases took place in nearby towns. Montgomery’s population increased modestly, but larger increases took place outside the city limits in eastern Montgomery County and in Autauga and Elmore Counties. Mobile’s population remained static, whereas the cities of Daphne and Fairhope in Baldwin County experienced significant growth. Comparisons of population shifts to trends in median household income by county suggest that exurban, residential, and commercial development outside cities and suburbs, driven by migration of middle and upper middle class families, is taking place in rural areas near Alabama’s largest urban spaces. In light of recent trends in “reurbanization,” the pace of migration to the suburbs has started to decline, prompting a heightened emphasis on residential and commercial re-development projects in and around central business districts.

Economics

Alabama has consistently ranked below the national average in terms of income and poverty, figures which have not changed in recent years. According to the 2010 Census, per-capita personal income in Alabama was $22,984 as compared with the $27,334 U.S. average. The state ranked 46th out of 50 states and the District of Columbia in the percentage of citizens living in poverty. The average number of persons living in poverty in Alabama in 2014 was estimated at approximately 16.9 percent, whereas the U.S. average was 12.3 percent. Nine out of the 10 poorest counties in Alabama—Lowndes, Hale, Macon, Pickens, Escambia, Barbour, Conecuh, Greene, Sumter, and Bullock—are in the Black Belt. According to the 2010 Census, the top 10 counties in median household income, ranked from highest to lowest, were Shelby, Madison, Jefferson, Baldwin, Montgomery, Autauga, Limestone, Morgan, Coffee, and Lee. Most of these counties surround the state’s major cities, and all of them, with the exception of Baldwin and Coffee Counties, are in the northern half of the state. Geographically, unemployment rates are lowest in Alabama’s northern counties. A few southern counties, including Baldwin, Coffee, Houston, and Pike, enjoy low unemployment rates as well.

In recent years, Alabama has been successful in attracting a variety of industries to the state, including steel and stainless steel, aircraft, automotive, and maritime businesses. As the state moves into the twenty-first century, the challenge will be to find additional ways to exploit its diverse physical and cultural geography in an increasingly competitive global setting.

Further Reading

- Flynt, Wayne. Alabama in the Twentieth Century. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Harris, W. Stuart. Dead Towns of Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1977.

- Rogers, William Warren, Robert David Ward, Leah Rawls Atkins, and Wayne Flynt. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State. Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 1994.