Confederate Navy in Alabama

CSS Alabama Sinking the USS Hatteras

Alabama played a key role in Confederate naval operations because of the state’s strategic and economic importance and its role in the defense of the Gulf Coast. Mobile was second only to New Orleans as a transit point for cotton, which was a major source of revenue for the Confederate government, as well as its principal diplomatic tool. Alabama‘s great rivers (including the Alabama, Tennessee, and Tombigbee) and its coastline were the site of fierce contests during the Civil War, including the Battle of Mobile Bay. The Alabama militia seized the Port of Mobile after the state seceded on January 11, 1861. Thereafter, the Alabama coast became the domain of smugglers, blockade runners, and focused efforts to bolster the naval defenses of Mobile Bay from Union attack. Raiders and blockade runners used Alabama’s waterways to great effect during the war as they slipped through to the Mississippi River to skirt the Union blockade.

CSS Alabama Sinking the USS Hatteras

Alabama played a key role in Confederate naval operations because of the state’s strategic and economic importance and its role in the defense of the Gulf Coast. Mobile was second only to New Orleans as a transit point for cotton, which was a major source of revenue for the Confederate government, as well as its principal diplomatic tool. Alabama‘s great rivers (including the Alabama, Tennessee, and Tombigbee) and its coastline were the site of fierce contests during the Civil War, including the Battle of Mobile Bay. The Alabama militia seized the Port of Mobile after the state seceded on January 11, 1861. Thereafter, the Alabama coast became the domain of smugglers, blockade runners, and focused efforts to bolster the naval defenses of Mobile Bay from Union attack. Raiders and blockade runners used Alabama’s waterways to great effect during the war as they slipped through to the Mississippi River to skirt the Union blockade.

On February 13, 1861, soon after the creation of the Confederate States of America, the Confederate Committee on Naval Affairs met in Montgomery and began to organize the Confederate Navy, recruit southern naval officers leaving the U.S. Navy, and prepare coastal defenses of the South’s five principal ports: New Orleans, Mobile, Pensacola, Savannah, and Charleston. One week later, on February 20, the Confederate Congress created the Department of the Navy and appointed Stephen Mallory, a former U.S. Senator from Florida and member of the Committee on Naval Affairs, as secretary of the Navy. Confederate leaders understood that naval power was crucial to the success of the southern war effort, but the government was never able to fund the department sufficiently, given the enormous coastline and river systems it was required to defend.

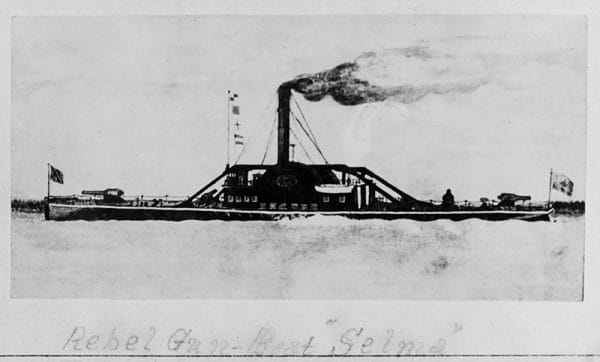

CSS Selma

Many Alabamians served as sailors and officers in the Confederate Navy, and the state provided much material to the war effort. In addition, the Civil War sparked a revolution in naval warfare and ship design, and Alabama was at the heart of this revolution. Montgomery, Mobile, Selma, and, briefly, the Oven Bluff shipyard on the Tombigbee River hosted innovative shipbuilding and repair facilities for the Confederate Navy. The production of iron for ships was very quickly understood to be one of the keys to naval victory in the Civil War, and Alabama was among the most important producers of iron in the South. Indeed, Alabama contributed more iron ore than any other Confederate state and by the end of the war was also producing more coal (which is essential in producing iron from ore) than any other state. Iron was used in naval ships in a variety of ways, including in the creation of fasteners such as nails, bolts, and nuts; in weapons such as heavy iron cannons, cannonballs, and shells; for rams used to sink enemy ships; and for engines, chains, and anchors.

CSS Selma

Many Alabamians served as sailors and officers in the Confederate Navy, and the state provided much material to the war effort. In addition, the Civil War sparked a revolution in naval warfare and ship design, and Alabama was at the heart of this revolution. Montgomery, Mobile, Selma, and, briefly, the Oven Bluff shipyard on the Tombigbee River hosted innovative shipbuilding and repair facilities for the Confederate Navy. The production of iron for ships was very quickly understood to be one of the keys to naval victory in the Civil War, and Alabama was among the most important producers of iron in the South. Indeed, Alabama contributed more iron ore than any other Confederate state and by the end of the war was also producing more coal (which is essential in producing iron from ore) than any other state. Iron was used in naval ships in a variety of ways, including in the creation of fasteners such as nails, bolts, and nuts; in weapons such as heavy iron cannons, cannonballs, and shells; for rams used to sink enemy ships; and for engines, chains, and anchors.

The state was home to four of the 39 iron furnaces in the Confederacy in 1860, and an additional 13 furnaces were built before the end of the war in 1865. Among the best-known manufacturers were the Bibb Iron Company, which was owned by the Confederate government, and the privately owned Shelby Iron Works, Cane Creek Iron works, and Brierfield Furnace. All but one of Alabama’s strategically significant iron furnaces were destroyed during the war; Hale & Murdock Ironworks in Lamar County escaped detection.

One of the most prolific and important iron producers for the Confederate Navy was the Selma Ordnance and Naval Foundry in Selma, which produced approximately 143 naval guns, such as howitzers and mortars, as well as thousands of rounds of artillery shot and shells. At the behest of Colin J. McRae, of the Committee on Naval Affairs, the Confederacy purchased the Selma-based Alabama Manufacturing Company, which was soon operated by the Confederate Navy as the Naval Gun Foundry. By the end of the war in 1865, this foundry supplied all the ammunition to the Confederate Navy.

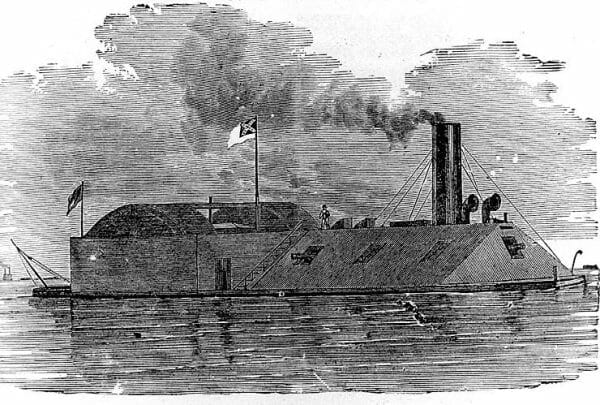

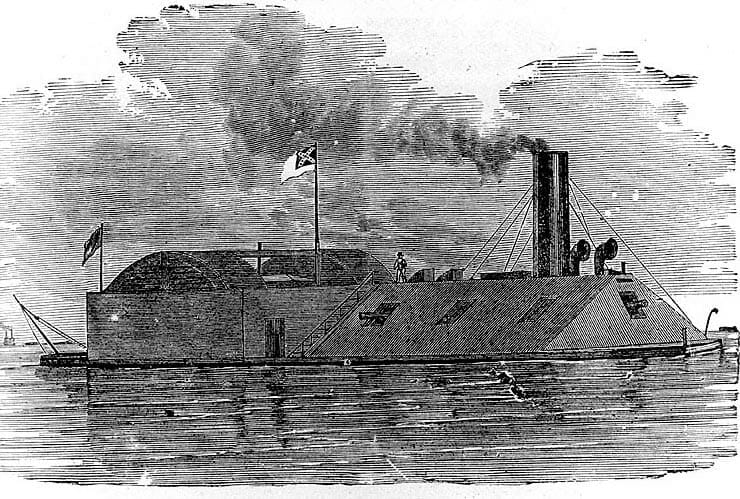

A new and innovative use for Alabama iron was the development of plate armor, which was installed on ships known as ironclads. These ships were largely impervious to shot and shell and soon made unarmored wooden ships obsolete. In 1861, the Confederacy moved rapidly to capitalize on the strategic promise of the ironclads and was the first side in the Civil War to begin building ironclads as its principal naval weapon. Early in the war, on November 8, 1861, the Alabama General Assembly appropriated $150,000 to build ironclad vessels for the defense of Mobile Bay. Alabama’s first ironclad was the CSS Baltic, which was used between 1862 and 1864 to defend Mobile Bay. This ironclad was created from an existing Philadelphia-built flat-bottomed lighter, a tug vessel used primarily to transfer cotton from the port in Mobile to ships moored in the bay. It was refitted into a warship and heavily armed with two Dahlgren guns and two 32-pound smooth-bore cannons, but it was slow and difficult to maneuver. The Baltic was sheathed in iron only above the waterline, and the wooden bottom was soon so eaten by parasites that the ship was retired.

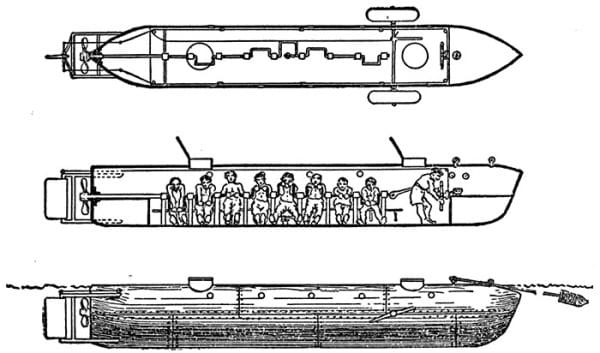

H. L. Hunley Diagram

Two ironclads built in Selma, the Huntsville and the Tuscaloosa, had engines so poor and slow that the ships were ultimately used as stationary batteries from which to fire upon enemy warships. In contrast, the Selma-built Tennessee, which carried six inches of iron armor, was widely considered to be one of the most robust ironclad ships built in the South. The ship was slow, however, and would meet its match when a Union fleet arrived at Mobile Bay. Perhaps the most innovative naval vessel crafted in Alabama was the H. L. Hunley, a submarine that was built and tested in Mobile Bay by James R. McClintock and Horace L. Hunley. The men had designed and built their first two submarines with limited success at their construction facility in New Orleans, but when the Union took control of the port city, McClintock and Hunley moved to Mobile to continue their experiments in creating an effective submarine. After several tragic failures, the vessel eventually proved itself, when it sank the USS Housatonic off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, in February 1864. The Hunley also sank in the effort, however, killing all aboard.

H. L. Hunley Diagram

Two ironclads built in Selma, the Huntsville and the Tuscaloosa, had engines so poor and slow that the ships were ultimately used as stationary batteries from which to fire upon enemy warships. In contrast, the Selma-built Tennessee, which carried six inches of iron armor, was widely considered to be one of the most robust ironclad ships built in the South. The ship was slow, however, and would meet its match when a Union fleet arrived at Mobile Bay. Perhaps the most innovative naval vessel crafted in Alabama was the H. L. Hunley, a submarine that was built and tested in Mobile Bay by James R. McClintock and Horace L. Hunley. The men had designed and built their first two submarines with limited success at their construction facility in New Orleans, but when the Union took control of the port city, McClintock and Hunley moved to Mobile to continue their experiments in creating an effective submarine. After several tragic failures, the vessel eventually proved itself, when it sank the USS Housatonic off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, in February 1864. The Hunley also sank in the effort, however, killing all aboard.

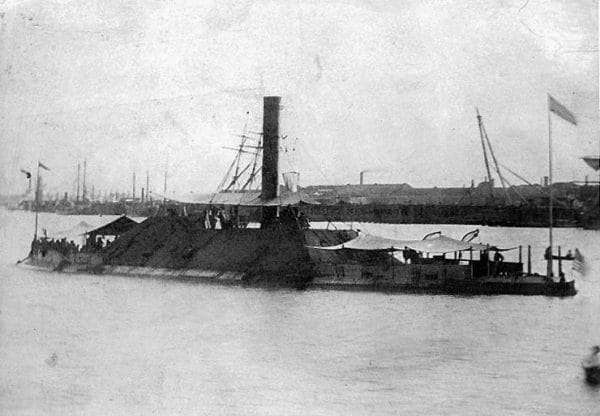

USS Tennessee

Mobile Bay was one of the most strategic ports on the Confederate coast, and it was the last important port in the Gulf of Mexico to fall. The 40-mile-long bay terminated at Mobile, which was Alabama’s largest city at the time. The defense of the bay fell to Confederate admiral Franklin Buchanan and his fleet of ironclads: the CSS Tennessee, CSS Gaines, CSS Morgan, and CSS Selma. Combined, these ships had 22 guns. The channel into the port ran between Mobile Point and Dauphin Island. This lane was protected by two forts heavily armed with coastal artillery: Fort Morgan to the east and Fort Gaines on the west. A third installation, Fort Powell, sat slightly to the northeast and protected the secondary shipping channel. As further protection for the approaches to the bay, the Confederate Navy also laid large torpedo mine fields in the waterway. These narrowed the entry to the port to a 450-yard channel through which all ships had to sail.

USS Tennessee

Mobile Bay was one of the most strategic ports on the Confederate coast, and it was the last important port in the Gulf of Mexico to fall. The 40-mile-long bay terminated at Mobile, which was Alabama’s largest city at the time. The defense of the bay fell to Confederate admiral Franklin Buchanan and his fleet of ironclads: the CSS Tennessee, CSS Gaines, CSS Morgan, and CSS Selma. Combined, these ships had 22 guns. The channel into the port ran between Mobile Point and Dauphin Island. This lane was protected by two forts heavily armed with coastal artillery: Fort Morgan to the east and Fort Gaines on the west. A third installation, Fort Powell, sat slightly to the northeast and protected the secondary shipping channel. As further protection for the approaches to the bay, the Confederate Navy also laid large torpedo mine fields in the waterway. These narrowed the entry to the port to a 450-yard channel through which all ships had to sail.

These defensive precautions proved to be important although ultimately inadequate, as Union admiral David G. Farragut and his fleet were resolved to conquer Mobile Bay. Farragut’s ships attacked at approximately 7 a.m. on August 5, 1864. The ironclad gunboat USS Tecumseh opened the battle by firing on Fort Morgan. While maneuvering for position under Confederate fire, the Tecumseh hit one of the many Confederate mines and sank in what Confederates recorded as less than 30 seconds. With the Union and Confederate ships now facing each other in the mouth of Mobile Bay, a furious and massive naval battle began. The Confederate ships managed to sink the USS Philippi before the Tennessee was massively battered from Union cannon fire and forced to surrender at 10 a.m. Yet it took until August 23 for the Union to force the surrender of Fort Morgan. At that point, the Union took final control of Mobile Bay.

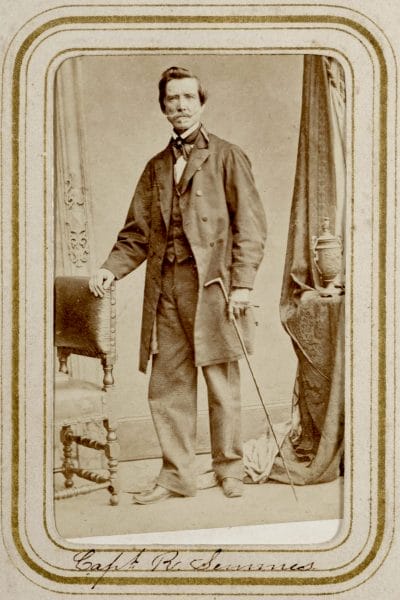

Raphael Semmes

Outside the state’s borders, the Confederate Navy also contributed to Alabama’s maritime heritage. The cruiser that bore the state’s name, the CSS Alabama, which was built in England in 1862, became one of the most fearsome and successful of the Confederate raiders. Under the command of naval giant Raphael Semmes, the Alabama captured or destroyed 65 ships before its defeat off the coast of France by the USS Kearsarge in 1864. Although it was unable to destroy the Union blockade and suffered a final defeat by a numerically and technologically superior opponent, the Confederate Navy left striking and important contributions to technological innovation, productivity, leadership, and resistance. Naval forces shrank in the post-war era as the ships were sold, retired, and rendered obsolete, but the legacy and memory of the Confederacy’s formidable and persistent challenges to a superior force remained.

Raphael Semmes

Outside the state’s borders, the Confederate Navy also contributed to Alabama’s maritime heritage. The cruiser that bore the state’s name, the CSS Alabama, which was built in England in 1862, became one of the most fearsome and successful of the Confederate raiders. Under the command of naval giant Raphael Semmes, the Alabama captured or destroyed 65 ships before its defeat off the coast of France by the USS Kearsarge in 1864. Although it was unable to destroy the Union blockade and suffered a final defeat by a numerically and technologically superior opponent, the Confederate Navy left striking and important contributions to technological innovation, productivity, leadership, and resistance. Naval forces shrank in the post-war era as the ships were sold, retired, and rendered obsolete, but the legacy and memory of the Confederacy’s formidable and persistent challenges to a superior force remained.

Further Reading

- Luraghi, Raimondo. A History of the Confederate Navy. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1996.

- Musicant, Ivan. Divided Waters: The Naval History of the Civil War. New York: HarperCollins, 1995.

- Still, William N., Jr. Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Ironclads. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1985.

- Still, William N. “Selma and the Confederate Navy.” Alabama Review 15 (January 1962): 19-37.