Eugene B. Sledge

Mobile native Eugene Sledge (1923-2001) is renowned outside of Alabama largely for his graphic portrayal of combat in the Pacific during World War II, With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa. Inside the state, he also was a professor of biology popular with students at the University of Montevallo, where he taught for many years.

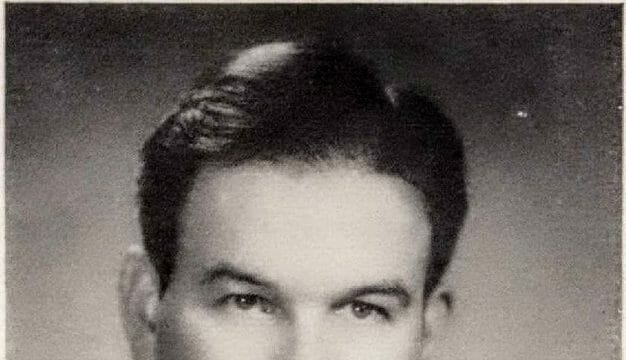

Eugene B. Sledge in 1982

Eugene Bondurant Sledge was born in Mobile on November 4, 1923, to Edward Simmons Sledge and Mary Frank Sturdivant. Sledge’s father was a physician with undergraduate and medical degrees from the University of Pennsylvania. His mother was the daughter of Ellen Rush Sturdivant, the dean of women at Huntingdon College in Montgomery. Sledge grew up in Georgia Cottage, an antebellum house on the outskirts of Mobile that once had been owned by nineteenth-century novelist Augusta Jane Evans. As a boy, Sledge spent many hours exploring Mobile Bay waterways observing nature (his father taught him to describe birds, animals, and features of the landscape—training that came in handy in his career as a biologist) and looking for Civil War relics. Two of Sledge’s ancestors on his mother’s side served as officers in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War, and Sledge maintained a lifelong interest in that conflict.

Eugene B. Sledge in 1982

Eugene Bondurant Sledge was born in Mobile on November 4, 1923, to Edward Simmons Sledge and Mary Frank Sturdivant. Sledge’s father was a physician with undergraduate and medical degrees from the University of Pennsylvania. His mother was the daughter of Ellen Rush Sturdivant, the dean of women at Huntingdon College in Montgomery. Sledge grew up in Georgia Cottage, an antebellum house on the outskirts of Mobile that once had been owned by nineteenth-century novelist Augusta Jane Evans. As a boy, Sledge spent many hours exploring Mobile Bay waterways observing nature (his father taught him to describe birds, animals, and features of the landscape—training that came in handy in his career as a biologist) and looking for Civil War relics. Two of Sledge’s ancestors on his mother’s side served as officers in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War, and Sledge maintained a lifelong interest in that conflict.

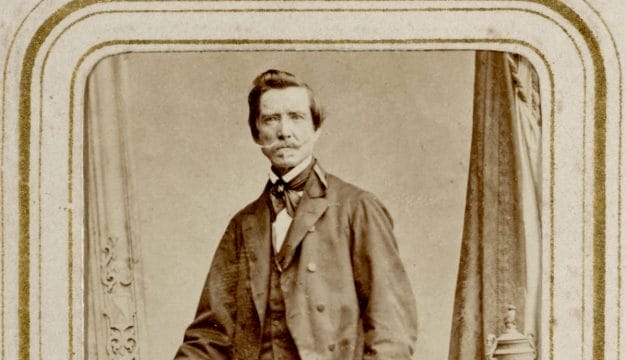

Sledge Family, 1942

Sledge graduated from Murphy High School in Mobile in 1942 and entered Marion Military Institute in Marion, Perry County. He then enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps at Marion in December 1942. After a brief stint at the Georgia Institute of Technology in an officers’ training program in 1943-44, he left the program to serve in the ranks as an enlisted man. Sledge received basic training at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego and at Camp Elliott (located near San Diego) and was assigned as a mortarman to Company K, Third Battalion, Fifth Regiment, First Marine Division.

Sledge Family, 1942

Sledge graduated from Murphy High School in Mobile in 1942 and entered Marion Military Institute in Marion, Perry County. He then enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps at Marion in December 1942. After a brief stint at the Georgia Institute of Technology in an officers’ training program in 1943-44, he left the program to serve in the ranks as an enlisted man. Sledge received basic training at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego and at Camp Elliott (located near San Diego) and was assigned as a mortarman to Company K, Third Battalion, Fifth Regiment, First Marine Division.

After additional training in New Caledonia and on Pavuvu in the Solomon Islands, Sledge saw heavy combat for the first time on the island of Peleliu in September 1944. The physical and emotional experience marked him for life. After rest and rehabilitation on Pavuvu and maneuvers on Guadalcanal and Ulithi, Sledge’s unit went into combat again on Okinawa on April 1, 1945. The battle for Okinawa was the costliest single campaign of the Pacific War: in almost three months of fighting, more than 50,000 U.S. soldiers, sailors, and Marines were killed, wounded, or listed as missing in action. Sledge, known as “Sledgehammer” to his comrades, was in combat on Okinawa for 82 days, until the island was declared secured on June 23, 1945. Despite the heavy casualties in his unit, he survived the war without being physically wounded. It took him years, however, to recover from the psychological aftereffects of combat.

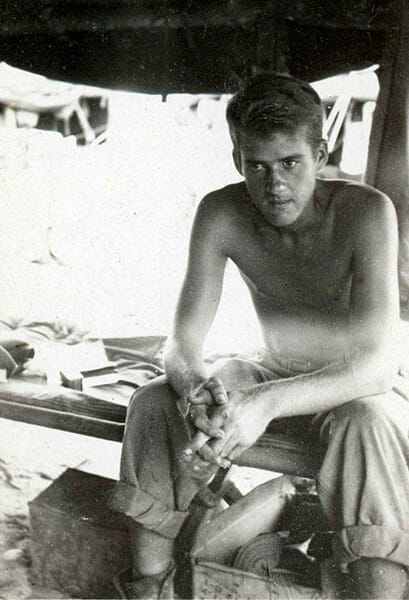

Eugene Sledge on Okinawa, 1945

After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, Sledge served in Beijing, China, as part of a U.S. occupation force. He was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps in February 1946 with the rank of corporal. Sledge returned to Alabama but found it hard to readjust to civilian life. He entered the Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) and earned a bachelor of science degree in business administration in 1949. After graduation, Sledge attempted to make a career in the insurance and real estate business in Mobile, but with little enthusiasm. Sledge married Jeanne Arceneaux of Mobile in 1952. The couple would have two sons: John (born 1957) and Henry (born 1965). On his father’s advice, Sledge returned to Auburn and earned a master of science degree in botany, writing his thesis on parasitic worms (nematodes) and their effect on varieties of corn.

Eugene Sledge on Okinawa, 1945

After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, Sledge served in Beijing, China, as part of a U.S. occupation force. He was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps in February 1946 with the rank of corporal. Sledge returned to Alabama but found it hard to readjust to civilian life. He entered the Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) and earned a bachelor of science degree in business administration in 1949. After graduation, Sledge attempted to make a career in the insurance and real estate business in Mobile, but with little enthusiasm. Sledge married Jeanne Arceneaux of Mobile in 1952. The couple would have two sons: John (born 1957) and Henry (born 1965). On his father’s advice, Sledge returned to Auburn and earned a master of science degree in botany, writing his thesis on parasitic worms (nematodes) and their effect on varieties of corn.

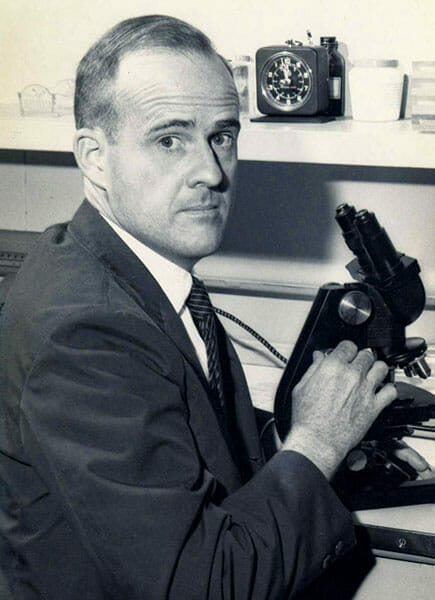

In 1960, Sledge graduated from the University of Florida with a doctorate in zoology. After working two years for the Florida State Department of Agriculture, he joined the biology faculty of Alabama College (now the University of Montevallo), where he taught introductory biology, physiology, and the history and philosophy of science, a favorite subject. He organized field trips and collecting expeditions around town and in neighboring counties and was regarded with affection by his colleagues and students. Sledge specialized in nematodes and their effects on crops and trees. He joined the Helminthological Society of Washington in 1956 and published numerous articles on nematodes in scientific journals. Sledge retired from Montevallo in 1990.

Eugene Sledge at the University of Montevallo

Sledge is best known not for his long academic career but as the author of two World War II memoirs: With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa (1981) and China Marine: An Infantryman’s Life after World War II (2002). Although With the Old Breed was published almost 40 years after the experiences it describes, its composition began during and soon after the war. Sledge kept clandestine notes during the fighting on Peleliu and Okinawa in a pocket edition of the New Testament that he had been issued at Camp Elliott, and his personal papers include a 1946 outline of the book that eventually became With the Old Breed. He drew on these and other materials when he started writing the memoir in earnest in the late 1970s. According to his son John, Sledge wrote the memoir at high speed, as if he were “taking dictation.” Sledge originally wrote about his war experiences for his family but was persuaded by his wife to seek publication. His second memoir, China Marine, describes Sledge’s postwar service in Beijing, his return to Mobile, and his gradual readjustment to civilian life; it was published posthumously in 2002.

Eugene Sledge at the University of Montevallo

Sledge is best known not for his long academic career but as the author of two World War II memoirs: With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa (1981) and China Marine: An Infantryman’s Life after World War II (2002). Although With the Old Breed was published almost 40 years after the experiences it describes, its composition began during and soon after the war. Sledge kept clandestine notes during the fighting on Peleliu and Okinawa in a pocket edition of the New Testament that he had been issued at Camp Elliott, and his personal papers include a 1946 outline of the book that eventually became With the Old Breed. He drew on these and other materials when he started writing the memoir in earnest in the late 1970s. According to his son John, Sledge wrote the memoir at high speed, as if he were “taking dictation.” Sledge originally wrote about his war experiences for his family but was persuaded by his wife to seek publication. His second memoir, China Marine, describes Sledge’s postwar service in Beijing, his return to Mobile, and his gradual readjustment to civilian life; it was published posthumously in 2002.

With the Old Breed has earned wide recognition from historians and veterans as one of the best first-hand accounts of combat in the Pacific during World War II. Sledge’s writing is characterized by straightforward, almost clinical descriptions of infantry combat and its physical and psychological effects, describing in detail the physical struggle of living in a combat zone and the debilitating effects of constant fear, fatigue, and filth. The memoir also contains harrowing episodes of brutality by U.S. Marines and Japanese soldiers alike, and Sledge wrote honestly of the hatred that both armies harbored for each other, manifested in the desecration of corpses that was practiced by both sides. Sledge described Marines “field stripping” dead Japanese soldiers—and, in one case, a severely wounded but still living Japanese soldier—for gold teeth and other trophies. The moral turning point of the book occurs when Sledge is dissuaded from pulling gold teeth from a Japanese corpse by his unit’s medical corpsman, who warned him that they might carry disease. Sledge reflects that the corpsman helped him retain some of his humanity.

Despite its emphasis on the horror and waste of war, With the Old Breed is distinguished by Sledge’s pride in his military service and his admiration for the bravery and sacrifices of his comrades. Nor did the wartime experiences turn Sledge toward pacifism. In the epilogue to his second memoir, China Marine, Sledge related that he did not lament using his mortar, rifle, and Thompson submachine gun to kill enemy soldiers, but did regret those he missed. This unapologetic statement may sound strange today, when the very notion of “the enemy” is a difficult concept for many Americans to grasp.

Sledge’s World War II memoirs have influenced other writers. Pulitzer Prize–winning author Louis “Studs” Terkel interviewed Sledge for his renowned oral history collection “The Good War” (1984). More recently, filmmaker Ken Burns drew heavily on Sledge’s memoirs for his 2007 PBS documentary on World War II, The War. Home Box Office (HBO) used With the Old Breed, and Robert Leckie’s Helmet for My Pillow as the basis for 2010 miniseries The Pacific, the successor to the 2001 HBO miniseries Band of Brothers.

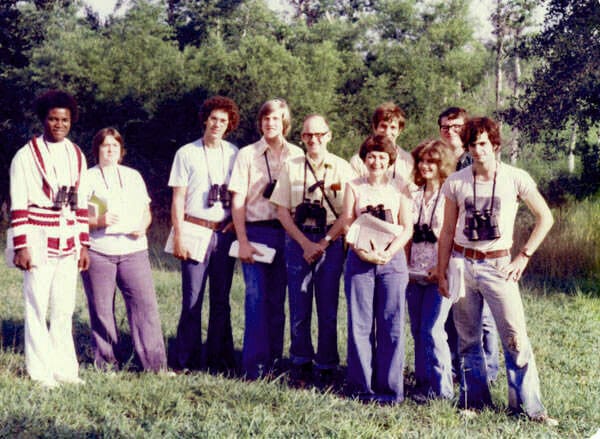

Eugene Sledge and Students

Overall, Sledge was a man of wide-ranging interests. As an avid lifelong ornithologist, he led bird-watching expeditions in Montevallo and other parts of the state. He read widely in history and philosophy and was fond of poetry, especially the works of Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, and other English soldier-poets of World War I. He enjoyed classical music and played classical guitar. By Sledge’s own account, classical music (especially Mozart) and the rigors of scientific research helped him recover from his war experiences. Sledge died of stomach cancer on March 3, 2001, and was buried in Pine Crest Cemetery in Mobile.

Eugene Sledge and Students

Overall, Sledge was a man of wide-ranging interests. As an avid lifelong ornithologist, he led bird-watching expeditions in Montevallo and other parts of the state. He read widely in history and philosophy and was fond of poetry, especially the works of Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, and other English soldier-poets of World War I. He enjoyed classical music and played classical guitar. By Sledge’s own account, classical music (especially Mozart) and the rigors of scientific research helped him recover from his war experiences. Sledge died of stomach cancer on March 3, 2001, and was buried in Pine Crest Cemetery in Mobile.

Further Reading

- Feifer, George. Tennozan: The Battle of Okinawa and the Atomic Bomb. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992.

- Fussell, Paul. Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Sledge, Eugene B. With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa. 1981. Reprint, Novato, Calif.: Presidio Press, 2007.

- ———. China Marine: An Infantryman’s Life after World War II. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- Sloan, Bill. Brotherhood of Heroes: The Marines at Peleliu, 1944: The Bloodiest Battle of the Pacific War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.