National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Alabama

NAACP in Alabama Logo

Beginning in 1913, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was the leading advocate for black constitutional rights in Alabama during the first half of the twentieth century. Other advocacy organizations existed, such as civic and voters’ leagues, but Alabama’s NAACP branches provided the most consistent and vocal challenge to African Americans’ second-class status in society before the modern civil rights movement. White supremacists viewed the NAACP as a threat to the status quo and used intimidation, violence, and the law to eliminate the various branches in the state. Finally, in 1956, the state outlawed the organization outright, which led to a loss of influence. Alabama NAACP branches also faced internal threats to their survival through ineffective leadership and factionalism. Faced with threats of white reprisal, loss of will on the part of some branch officials and members, and competition from the Communist Party, the Alabama NAACP’s crusade for racial equality was still able to generate the opposition to disenfranchisement and Jim Crow laws that would later define the 1950s and 1960s.

NAACP in Alabama Logo

Beginning in 1913, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was the leading advocate for black constitutional rights in Alabama during the first half of the twentieth century. Other advocacy organizations existed, such as civic and voters’ leagues, but Alabama’s NAACP branches provided the most consistent and vocal challenge to African Americans’ second-class status in society before the modern civil rights movement. White supremacists viewed the NAACP as a threat to the status quo and used intimidation, violence, and the law to eliminate the various branches in the state. Finally, in 1956, the state outlawed the organization outright, which led to a loss of influence. Alabama NAACP branches also faced internal threats to their survival through ineffective leadership and factionalism. Faced with threats of white reprisal, loss of will on the part of some branch officials and members, and competition from the Communist Party, the Alabama NAACP’s crusade for racial equality was still able to generate the opposition to disenfranchisement and Jim Crow laws that would later define the 1950s and 1960s.

Early History

Black Alabamians were among the first southerners to establish an NAACP branch. Faculty, staff, and local citizens associated with Talladega College, in Talladega, founded the first branch in 1913, just four years after the formation of the parent agency in New York City and four years before any other southern state organized an NAACP branch. This first branch lasted only a year, however, because college officials dismissed William Pickens, who had been an organizer for the national NAACP office since 1910. Talladega College officials charged the controversial professor of languages with insubordination, promoting strife between white administrators and black students, and excessive absences from classes for his time spent recruiting and fundraising for the NAACP’s New York office. Pickens’s sudden departure brought the Talladega branch to an abrupt end.

The World War I call to “make the world safe for democracy” heightened awareness of inequality and caused discontent among African Americans living with segregation and Jim Crow in Alabama and other southern states, particularly among blacks serving in the military. The NAACP, with its already strong reputation for fighting segregation, quickly gained a large following in the state. In 1918, the first of 13 post-World War I branches was founded in Montgomery. African Americans in Alabama soon formed NAACP branches across the state in industrial regions, farming areas, and in cities large and small. The Alabama NAACP’s record of organizing local units of the militant protest group placed Alabama blacks in the forefront of NAACP formation in the South.

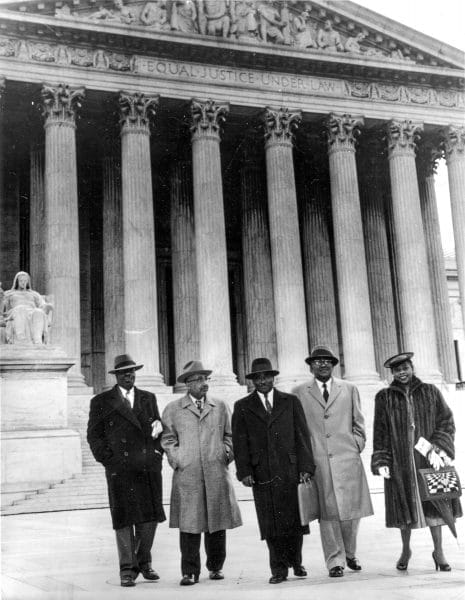

NAACP Leaders in Washington, D.C.

The 1940s represented the height of NAACP organizing in Alabama. By the mid-1940s, Alabama boasted 35 branches with nearly 15,000 members. In part, this growth was prompted by a number of successful court cases filed by the national office to challenge discrimination in housing, public spaces, and education, among others. But the phenomenal expansion was primarily a result of black Alabamians’ growing outrage with racial biases, heightened by entry into World War II. Racist policies within the military and wartime industries fueled resentment and fostered a spirit of protest. The result was an explosion in NAACP activism in the state and throughout the South.

NAACP Leaders in Washington, D.C.

The 1940s represented the height of NAACP organizing in Alabama. By the mid-1940s, Alabama boasted 35 branches with nearly 15,000 members. In part, this growth was prompted by a number of successful court cases filed by the national office to challenge discrimination in housing, public spaces, and education, among others. But the phenomenal expansion was primarily a result of black Alabamians’ growing outrage with racial biases, heightened by entry into World War II. Racist policies within the military and wartime industries fueled resentment and fostered a spirit of protest. The result was an explosion in NAACP activism in the state and throughout the South.

These efforts expanded further in 1945, when Alabama NAACP leaders—headed by Birmingham branch president Emory Jackson, Montgomery branch leader Edgar Daniel (E. D.) Nixon, and Mobile branch secretary John L. LeFlore—formed a statewide conference of branches that provided opportunities for developing a common approach to eliminating white supremacy and offered occasions for fundraising unavailable to individual branches.

Membership

The national office required 50 members for a branch to receive an official NAACP charter. National officials encouraged branch organizers to recruit members from key individuals in their communities, and Alabama branches generally followed this directive. NAACP membership in the state generally came from the black middle classes and included physicians, attorneys, ministers, businessmen, government workers, skilled laborers, and railroad employees. One result of this practice was that Alabama branch organizers seldom solicited members from the black working class, so this sector had little representation in most of the state’s NAACP branches. Black laborers and domestics comprised only between 5 and 10 percent of a typical branch’s members. Nevertheless, African American working-class individuals often identified with the NAACP’s agenda and regularly petitioned for assistance.

Some Alabama branch leaders recognized the need to include the working classes in NAACP efforts. For example, E. D. Nixon, who served as president of the Montgomery branch from 1946-1949 and the State Conference of Branches from 1947-1949, insisted that the local branch reach out to the African American working classes. Nixon was a Pullman porter and member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, but he did not abandon his roots as the son of a sharecropper. In 1947, when he ran for reelection as branch president, Nixon mounted his campaign on the slogan that he represented “the masses and not the classes.”

Rosa Parks and Johnnie Carr, 1985

Membership was largely male in the early years of organizing, but African American middle-class women began to join branches in unprecedented numbers beginning in the late 1930s and held important positions in some branches. For instance, women comprised more than 55 percent of the Montgomery branch’s total membership during the early 1940s. They composed 20 percent of the branch’s Executive Committee and chaired the Veterans’ Affairs Committee. Several woman held the post of secretary of the Montgomery NAACP—an extremely important position given this officer’s role as liaison with the New York headquarters. Two of the best-known secretaries of the Montgomery branch were Johnnie Carr and Rosa Parks, who both participated in the Montgomery Bus Boycott and came to symbolize the role of black women in the fight for full rights. Activist and cook Georgia Gilmore organized the “Club from Nowhere,” a group of women who cooked and sold food to raise money for the boycott and also accepted anonymous donations, and she also fed boycotters and movement leaders in her Montgomery home.

Rosa Parks and Johnnie Carr, 1985

Membership was largely male in the early years of organizing, but African American middle-class women began to join branches in unprecedented numbers beginning in the late 1930s and held important positions in some branches. For instance, women comprised more than 55 percent of the Montgomery branch’s total membership during the early 1940s. They composed 20 percent of the branch’s Executive Committee and chaired the Veterans’ Affairs Committee. Several woman held the post of secretary of the Montgomery NAACP—an extremely important position given this officer’s role as liaison with the New York headquarters. Two of the best-known secretaries of the Montgomery branch were Johnnie Carr and Rosa Parks, who both participated in the Montgomery Bus Boycott and came to symbolize the role of black women in the fight for full rights. Activist and cook Georgia Gilmore organized the “Club from Nowhere,” a group of women who cooked and sold food to raise money for the boycott and also accepted anonymous donations, and she also fed boycotters and movement leaders in her Montgomery home.

African American youth were an important component within some Alabama NAACP branches immediately before the civil rights crusade. Rosa Parks presided over the youth group associated with the Montgomery NAACP during the early-to-late 1950s. This group of young activists included 15-year-old Claudette Colvin, who was jailed in March 1955 for refusing to relinquish her bus seat to a white person.

Although the vast majority of white Alabamians viewed the NAACP as a subversive and dangerous organization whose goal was to undermine racial control, several attended organizational meetings of the Birmingham branch in 1932. Many notable white citizens signed on as NAACP members the next year, making the Birmingham branch a truly interracial organization.

Goals and Activities

Alabama branches often faced tremendous obstacles in retaining active status. Competing factions and goals weakened the cohesion of the units, and many branches faced the problem of NAACP officers who saw their posts primarily as a way of enhancing their own social prestige. Such branches generally accomplished little, except during local or national crises, such as the Scottsboro Trials.

John LeFlore

Even the well-run branches faced immense challenges in carrying out the NAACP’s goals. The national organization had been founded in 1909 to secure blacks’ complete citizenship rights, chiefly through legal efforts, lobbying, and the media. But confronting white supremacy in Alabama, using these and other methods, could result in intimidation on the job, firings, physical harm, and sometimes death. W. E. Morton, secretary of the Mobile branch, was nearly killed by a white mob in 1921 as he conducted NAACP business in nearby Camden. John LeFlore, Mobile branch secretary from 1926 to 1956, endured continual harassment from his white post office supervisors because of his NAACP activities. In the 1930s, police arrested Earnest Taggart as he posted flyers announcing the Birmingham branch’s anti-lynching crusade and issued bogus traffic citations to NAACP members during the branch’s campaign against police violence. In the 1940s, Birmingham law enforcement officers snatched NAACP buttons from the clothing of local branch members amid the organization’s ongoing effort to end police brutality.

John LeFlore

Even the well-run branches faced immense challenges in carrying out the NAACP’s goals. The national organization had been founded in 1909 to secure blacks’ complete citizenship rights, chiefly through legal efforts, lobbying, and the media. But confronting white supremacy in Alabama, using these and other methods, could result in intimidation on the job, firings, physical harm, and sometimes death. W. E. Morton, secretary of the Mobile branch, was nearly killed by a white mob in 1921 as he conducted NAACP business in nearby Camden. John LeFlore, Mobile branch secretary from 1926 to 1956, endured continual harassment from his white post office supervisors because of his NAACP activities. In the 1930s, police arrested Earnest Taggart as he posted flyers announcing the Birmingham branch’s anti-lynching crusade and issued bogus traffic citations to NAACP members during the branch’s campaign against police violence. In the 1940s, Birmingham law enforcement officers snatched NAACP buttons from the clothing of local branch members amid the organization’s ongoing effort to end police brutality.

Alabama NAACP’s leaders struggled to overcome internal strife and external racism. In the 1930s, Alabama branches confronted racially biased New Deal agencies and worked for the release of the Scottsboro defendants. During World War II, they protested discrimination against blacks in the military and in war-related industries and agencies. A key objective of the Alabama Conference of NAACP Branches in the early-to-mid 1950s was the abrogation of the state’s biracial system of graduate education. Likewise, the Jim Crow era saw Alabama branches and the statewide conference attack the discrimination African Americans faced in their communities, specifically discrimination in employment, unequal teacher salaries, segregation in public places, and unequal accommodations on public carriers. The Mobile branch, for instance, contested race-based restrictions on interstate trains and city buses. In 1942, 13 years before black residents of Montgomery initiated a boycott of city buses, the Mobile branch threatened a strike against the local transit system after the murder of a black soldier on one of the vehicles and the long-term abuse of black patrons. Lynching, race-based zoning, and police brutality were more sinister forms of racial injustice challenged by Alabama NAACP branches. The state’s branches directed the bulk of their attention to confronting disenfranchisement and discrimination against African Americans by the state’s judicial system.

Alabama NAACP branches fought the state’s persistent forms of discrimination in employment, teacher salaries, and school funding, segregation in public places, electoral rules and regulations, and unequal accommodations on public carriers in a variety of ways. They organized mass meetings, produced flyers and informational reports to arouse public support of their agenda, and submitted petitions and formal complaints to legislators and other officials. The lynching of African Americans prompted branches to investigate the facts behind mob violence and lobby the U.S. Congress to pass legislation making such acts a violation of federal law. Violations of blacks’ Fifteenth Amendment rights persuaded branches to establish voter education classes, sponsor registration campaigns, and initiate voting right cases.

Autherine Lucy, 1956

Alabama branches used legal means to overturn racial zoning and racially discriminating public teacher’ salaries, and they hired lawyers to represent African Americans charged with crimes against whites, such as rape or murder, and used the courts to prosecute whites accused of crimes against African Americans. By the time the Montgomery Bus Boycott began in December 1955, Alabama NAACP activism had created a climate of organized, determined racial protest. The activities executed by the state’s branches had achieved enhanced employment opportunities, legal measures calling for more equitable teacher salaries, court decrees outlawing discrimination in voting and racial zoning, and improved interstate railroad accommodations. In Mobile, the branch’s protest against the unfair treatment of blacks on municipal buses led the city to implement a “first-come, first served” seating arrangement in 1942. In 1956, NAACP agitation also forced the University of Alabama to admit, if only for a few days, Autherine Lucy. Most importantly, the branches’ energetic efforts saved blacks from unjust prison terms as well as from death sentences imposed on the basis of race. Also in 1956, the national office provided legal assistance to Montgomery blacks in the Browder v. Gayle case, which declared Jim Crow bus service unconstitutional.

Autherine Lucy, 1956

Alabama branches used legal means to overturn racial zoning and racially discriminating public teacher’ salaries, and they hired lawyers to represent African Americans charged with crimes against whites, such as rape or murder, and used the courts to prosecute whites accused of crimes against African Americans. By the time the Montgomery Bus Boycott began in December 1955, Alabama NAACP activism had created a climate of organized, determined racial protest. The activities executed by the state’s branches had achieved enhanced employment opportunities, legal measures calling for more equitable teacher salaries, court decrees outlawing discrimination in voting and racial zoning, and improved interstate railroad accommodations. In Mobile, the branch’s protest against the unfair treatment of blacks on municipal buses led the city to implement a “first-come, first served” seating arrangement in 1942. In 1956, NAACP agitation also forced the University of Alabama to admit, if only for a few days, Autherine Lucy. Most importantly, the branches’ energetic efforts saved blacks from unjust prison terms as well as from death sentences imposed on the basis of race. Also in 1956, the national office provided legal assistance to Montgomery blacks in the Browder v. Gayle case, which declared Jim Crow bus service unconstitutional.

Alabama authorities reacted to these victories by outlawing the NAACP in 1956. State Attorney General John Patterson justified this action by alleging that the NAACP had failed to register as an out-of-state organization. A series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions overruled Alabama courts and returned the group to the state eight years later. But by this time, other regional civil rights organizations had filled the vacuum, principally the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), formed in 1957, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), formed in 1960. Local black advocacy groups had, likewise, filled the void. The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), organized in 1955; Fred Shuttlesworth‘s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), founded in Birmingham in 1956; and Mobile’s Non-Partisan Voters League, also founded in 1956, became the new voices of African American civil rights in their localities. New generations of black Alabamians identified with these groups and their emphasis on direct action in contrast to the NAACP’s legal approach. Further, proponents of Black Power, with its origins in Alabama’s Lowndes County Freedom Organization, would soon take center stage in the national fight for civil rights in the 1960s. Other organizations, such as Mobile’s Neighborhood Organized Workers would use direct action to further local civil rights efforts.

The NAACP never regained its original prominence in the state. But NAACP branches had, over the years, created the groundswell that would place Alabama at the center of the modern struggle for social justice. Currently, the Alabama NAACP has approximately 35 branches that focus their efforts on disaster relief and continuing instances of racial prejudice, such as job discrimination. The state president is Edward Vaughn, former Michigan State Representative and Alabama native; the state NAACP headquarters is in Dothan. Branch offices are located in Eufaula, Barbour County; Clanton, Chilton County; and Mobile, Mobile County.

Further Reading

- Autrey, Dorothy A. “The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Alabama, 1913–1952.” Ph. D diss., University of Notre Dame, 1985.

- Brinkley, Douglas. Rosa Parks. New York: Penguin, Putnam, Inc., 2000.

- Kellogg, Charles F. NAACP: A History of National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1967.