Quilting

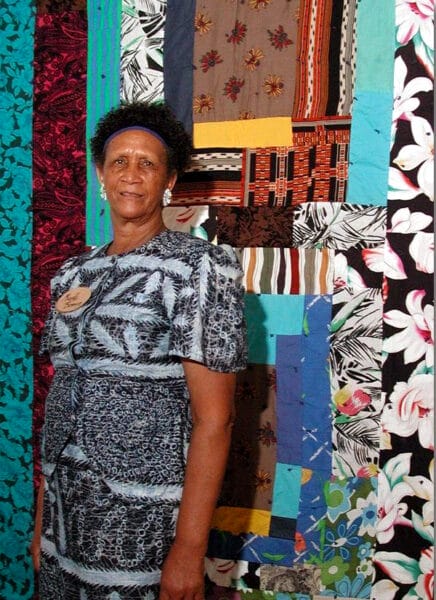

Mozell Benson

Quilt making has a long history in Alabama. Early settlers created bedcovers both for necessity and pleasure, and the pieced and quilted layers of fabric provided warmth and beauty in a new and often harsh environment. The craft continued even as modern textiles came to replace quilts in everyday use. Alabama practitioners range from those who make traditional quilts to those who work in studios and create art quilts. The quilters of Gee’s Bend, in Wilcox County, are renowned for their innovative and sophisticated quilt designs and have garnered particular attention and praise. Although styles and methods in the craft have changed as society has changed, quilt making continues as an active and vibrant tradition today.

Mozell Benson

Quilt making has a long history in Alabama. Early settlers created bedcovers both for necessity and pleasure, and the pieced and quilted layers of fabric provided warmth and beauty in a new and often harsh environment. The craft continued even as modern textiles came to replace quilts in everyday use. Alabama practitioners range from those who make traditional quilts to those who work in studios and create art quilts. The quilters of Gee’s Bend, in Wilcox County, are renowned for their innovative and sophisticated quilt designs and have garnered particular attention and praise. Although styles and methods in the craft have changed as society has changed, quilt making continues as an active and vibrant tradition today.

In the early nineteenth century, as settlers moved west into Alabama territory, they brought what possessions they could carry as well as the traditions of their previous communities. Thus, handmade textiles and needlework created in Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Tennessee were brought to Alabama, and some survive today. Such pieces served as guides for textiles made by early settlers. The types and styles of needlework developed by these new Alabamians followed national styles but were influenced by other factors, including family and community traditions, availability of materials, local examples, emerging trends in ladies’ magazines and published patterns, and, after the mid-nineteenth century, exhibits at state and county fairs.

Quilts are among the best-preserved and best-documented of Alabama textiles. It should be noted, however, that fabric was expensive and the making of quilts required a great deal of time, thus quilts from the early nineteenth century were most often made by individuals and families with greater resources. Blankets and woven coverlets more often served as the primary bedcovering for the members of other socio-economic classes.

Whole-Cloth Quilt

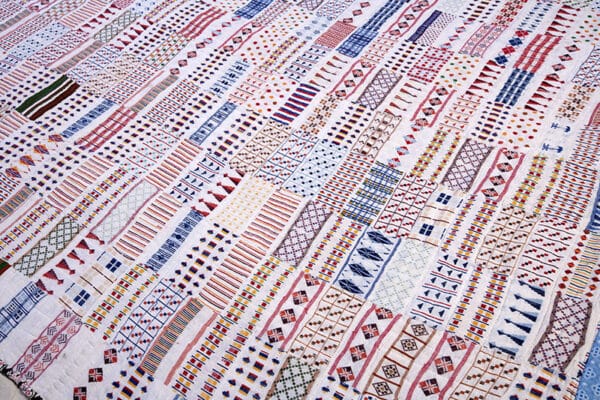

Two of the earliest Alabama-made quilts illustrate the dominance of national styles: an 1810 whole-cloth, all-white spread, and a quilt made around 1800 with cut-out printed cottons arranged in decorative designs. Both styles represent the earliest types of bedcovers in America. Whole-cloth quilts are bedcoverings made from one large piece of fabric or several widths of fabric seamed together to give the appearance of one piece. This type of bedcover is most typical of the whole-cloth quilts found in Alabama, and although they can be made from either cotton, linen or silk fabric, the Alabama examples are all cotton. Sometimes they are true quilts—three layers, bound together with quilting stitches—and sometimes they are unlined spreads with decorative embroidery covering the surface. All-white quilts and spreads, inspired by European styles, reached the height of their popularity between 1790 and 1810, but they continued to be made and imported throughout the nineteenth century.

Whole-Cloth Quilt

Two of the earliest Alabama-made quilts illustrate the dominance of national styles: an 1810 whole-cloth, all-white spread, and a quilt made around 1800 with cut-out printed cottons arranged in decorative designs. Both styles represent the earliest types of bedcovers in America. Whole-cloth quilts are bedcoverings made from one large piece of fabric or several widths of fabric seamed together to give the appearance of one piece. This type of bedcover is most typical of the whole-cloth quilts found in Alabama, and although they can be made from either cotton, linen or silk fabric, the Alabama examples are all cotton. Sometimes they are true quilts—three layers, bound together with quilting stitches—and sometimes they are unlined spreads with decorative embroidery covering the surface. All-white quilts and spreads, inspired by European styles, reached the height of their popularity between 1790 and 1810, but they continued to be made and imported throughout the nineteenth century.

Chintz Quilt

The other popular style was the quilt or spread made from chintz, a cotton fabric also known as calico, that was produced by Indian and English manufacturers and printed with various floral and other all-over patterns. These expensive fabrics first came to North America during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Most early chintz bedcovers followed the European style and featured a central medallion or tree-of-life design, sometimes surrounded by a series of borders framing the central design. Medallion quilts were especially popular during the early nineteenth century, but they never went out of fashion completely. Chintz continued to be used in quilts through the middle of the nineteenth century but was mainly used for borders, in sashes (strips dividing the blocks), or as individual blocks, rather than as the dominant element. Only the affluent could afford these expensive fabrics, and the Alabama-made quilts with these fabrics that survive from the first half of the nineteenth century are primarily those that were often termed “best quilts” and created and used for special occasions. As fabric became more widely available and affordable through trade and local production, quilt production expanded as well.

Chintz Quilt

The other popular style was the quilt or spread made from chintz, a cotton fabric also known as calico, that was produced by Indian and English manufacturers and printed with various floral and other all-over patterns. These expensive fabrics first came to North America during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Most early chintz bedcovers followed the European style and featured a central medallion or tree-of-life design, sometimes surrounded by a series of borders framing the central design. Medallion quilts were especially popular during the early nineteenth century, but they never went out of fashion completely. Chintz continued to be used in quilts through the middle of the nineteenth century but was mainly used for borders, in sashes (strips dividing the blocks), or as individual blocks, rather than as the dominant element. Only the affluent could afford these expensive fabrics, and the Alabama-made quilts with these fabrics that survive from the first half of the nineteenth century are primarily those that were often termed “best quilts” and created and used for special occasions. As fabric became more widely available and affordable through trade and local production, quilt production expanded as well.

Star Design Quilt

During the second quarter of the nineteenth century, American quilt makers moved away from these styles to a distinctly American patchwork style of repeating blocks, both pieced and appliquéd. The term “pieced” refers to the sewing technique by which pieces of fabric are cut into shapes and then stitched together at the edges to create patterns. “Appliqué” is a technique in which a piece of fabric cut into a decorative shape is sewn onto a larger ground fabric to create a design. Quilt makers found it easier to assemble small squares into a large top than to work a large expanse of fabric, as with a whole-cloth quilt. Pieced and appliquéd blocks allowed for variety in pattern and color. Quilts of this type were made in endless variation across Alabama, both as best quilts and everyday or utility quilts. The block designs were based on an endless variety of images, including flowers, stars, trees, and other inspirations from the natural world as well as inventive variations on geometric shapes.

Star Design Quilt

During the second quarter of the nineteenth century, American quilt makers moved away from these styles to a distinctly American patchwork style of repeating blocks, both pieced and appliquéd. The term “pieced” refers to the sewing technique by which pieces of fabric are cut into shapes and then stitched together at the edges to create patterns. “Appliqué” is a technique in which a piece of fabric cut into a decorative shape is sewn onto a larger ground fabric to create a design. Quilt makers found it easier to assemble small squares into a large top than to work a large expanse of fabric, as with a whole-cloth quilt. Pieced and appliquéd blocks allowed for variety in pattern and color. Quilts of this type were made in endless variation across Alabama, both as best quilts and everyday or utility quilts. The block designs were based on an endless variety of images, including flowers, stars, trees, and other inspirations from the natural world as well as inventive variations on geometric shapes.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Alabama’s textile industry was firmly established, and by 1860, the South was manufacturing one-third of the nation’s yarn and marketing it outside the region. There were also numerous fully integrated factories for the production of cloth, including spinning, weaving, and, in some instances, dyeing. Most of these mills produced osnaburg—a coarse fabric used primarily in clothing for the enslaved population—but some produced finer cloth for a variety of uses. Although it is not known how much Alabama-made fabric was used in comparison with fabric produced outside the state, it is clear that many mills were successful, so Alabamians must have taken advantage of the opportunity to buy locally.

In spite of these new industries and the availability of imported items, southerners had to continue producing most of the material goods needed for their daily lives because they were poorer and usually lived far from market sources of these items. The time-consuming nature of textile production required the combined efforts of all the women in a household. Cloth making and sewing were the two household tasks in which wives of plantation owners participated in the actual labor. In their accounts, these women rarely discuss sewing alongside enslaved household labor, but they do write that enslaved women helped with the sewing, weaving, and quilting. Much of the evidence for their early participation in quilting is based on oral history, letters, or diaries, and although it is not always possible to document specific examples, there certainly is a long and continuous involvement of African Americans in quilt-making in Alabama, and in the United States as a whole.

Crazy Quilt Detail

Africans were not familiar with bed quilts but did know the techniques used to make them—stitching, piecing, and appliqué—and enslaved and freed blacks became part of the American quilt-making tradition. Strong textile traditions exist in Africa and many of the Africans brought to America and forced into slavery came from west and central Africa. Both Ghana and Benin are well known for their stitched and appliquéd wall hangings and tapestries. In addition, throughout west Africa men wove cloth on narrow looms and then sewed the strips together to form a larger textile.

Crazy Quilt Detail

Africans were not familiar with bed quilts but did know the techniques used to make them—stitching, piecing, and appliqué—and enslaved and freed blacks became part of the American quilt-making tradition. Strong textile traditions exist in Africa and many of the Africans brought to America and forced into slavery came from west and central Africa. Both Ghana and Benin are well known for their stitched and appliquéd wall hangings and tapestries. In addition, throughout west Africa men wove cloth on narrow looms and then sewed the strips together to form a larger textile.

African Americans struggled to establish themselves after Emancipation, and many people remained where they were, working for wages or shares, and almost all growing cotton. However, fluctuating prices created uncertainty and instability among these smaller farmers and sharecroppers, both black and white. As the economy fluctuated, so did the family’s purchasing power. In some years, it was possible to buy new fabric for dresses and quilts; in other years it was not. It was during these lean times that quilters became innovative in their use of materials, using scraps, worn-out clothing, and flour and sugar sacks to produce creative designs.

In the South, including Alabama, quilting was generally performed within the family unit. Women’s diaries do mention friends or relatives coming to visit and quilt, but with the long distances between most homes it was not a common occurrence during the nineteenth century. However, by the end of the century, as more people came to live in towns, social quilting, in the form of quilting bees, increased. Many of these gatherings were in churches or missionary societies, with the quilts created as fundraisers for a variety of civic and political causes.

By the 1860s, wealthy households in Alabama began buying and using sewing machines. Women’s letters and diaries of the time indicate that they shared the machines amongst various homes, thus easing the burden of clothing production. The years following the Civil War brought gradual changes in other areas of textile production. Cotton production increased, as did the number of textile mills. Some of the fabric produced was not as fine as during the prewar period, but higher production resulted in decreased cost, and the greater availability of fabric encouraged innovations among quilters and quilt making. A wide variety of patterns emerged, creating a greater diversity of pieced and appliquéd designs during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Sources for quilt designs were many: ladies magazines featured ideas for handiwork, friends shared patterns in letters, and quilt displays at state and county fairs offered inspiration for patterns, fabrics, and techniques.

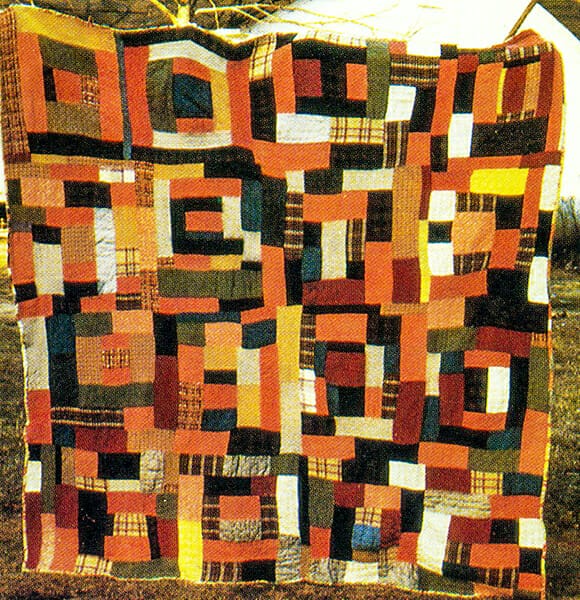

Crazy Quilt

The design known as the crazy quilt became popular during the late nineteenth century. This style was heavily influenced by Japanese designs popularized at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Called crazy quilts for their random patchworking and blocks of varying sizes and shapes, they were often made from silks, velvets, and satins and embroidered with an almost endless variety of fancy stitches. Makers sometimes incorporated treasures such as political or military campaign ribbons and added elaborately embroidered initials, insects, flora, fauna, and hand-painted scenes on silk. These pieces were not for use on the bed, but were intended as decorative throws or for display in parlors and sitting rooms. The style remained popular until about 1890, and although quilters generally abandoned working with elaborate fabrics, many continued to construct quilts in the crazy style in wool or cotton, reflecting their utilitarian rather than decorative use into the early twentieth century.

Crazy Quilt

The design known as the crazy quilt became popular during the late nineteenth century. This style was heavily influenced by Japanese designs popularized at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Called crazy quilts for their random patchworking and blocks of varying sizes and shapes, they were often made from silks, velvets, and satins and embroidered with an almost endless variety of fancy stitches. Makers sometimes incorporated treasures such as political or military campaign ribbons and added elaborately embroidered initials, insects, flora, fauna, and hand-painted scenes on silk. These pieces were not for use on the bed, but were intended as decorative throws or for display in parlors and sitting rooms. The style remained popular until about 1890, and although quilters generally abandoned working with elaborate fabrics, many continued to construct quilts in the crazy style in wool or cotton, reflecting their utilitarian rather than decorative use into the early twentieth century.

New Deal Quilt

In the early twentieth century, quilt makers in Alabama continued to make quilts for warmth, comfort, and the satisfaction of creating a beautiful object, although quilt making became less popular among upper and middle class women. But by the 1920s, the Colonial Revival movement in the decorative arts brought renewed interest in quilt making. Women of all economic levels began making quilts, and the more affluent were able to purchase patterns and new material for their quilts. Appliquéd floral designs became popular in about 1915 and remained so into the 1930s, as did pastel colors in shades of pink, lavender, blue, and mint green. This palette was so distinctive that these quilts became known collectively as Depression quilts. Quilt making declined in popularity during World War II but revived in the late 1960s. This era, with its embrace of alternative lifestyles and a rejection of much that was machine-produced, brought an enthusiasm for handmade items.

New Deal Quilt

In the early twentieth century, quilt makers in Alabama continued to make quilts for warmth, comfort, and the satisfaction of creating a beautiful object, although quilt making became less popular among upper and middle class women. But by the 1920s, the Colonial Revival movement in the decorative arts brought renewed interest in quilt making. Women of all economic levels began making quilts, and the more affluent were able to purchase patterns and new material for their quilts. Appliquéd floral designs became popular in about 1915 and remained so into the 1930s, as did pastel colors in shades of pink, lavender, blue, and mint green. This palette was so distinctive that these quilts became known collectively as Depression quilts. Quilt making declined in popularity during World War II but revived in the late 1960s. This era, with its embrace of alternative lifestyles and a rejection of much that was machine-produced, brought an enthusiasm for handmade items.

Gee’s Bend Quilters

Notable in this era was the creation of the quilting cooperatives among two groups of African American women in south-central Alabama. Both the Gee’s Bend quilting community of Boykin, Wilcox County, and the Freedom Quilting Bee, of nearby Alberta, grew out of the civil rights movement and gained national attention for the bold and innovative designs on their quilts. Self-taught Tuscaloosa artist Yvonne Wells would adopt civil rights themes in her “picture” quilts beginning in the 1980s; her works have been exhibited in the National Museum of African American History and the International Quilt Museum. In 2002, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts produced a major traveling exhibit and accompanying book that brought international attention to Gee’s Bend quilters, to their isolated community, and to the cultural continuity these objects reveal. The quilt makers have continued the same innovative and inspired approach to their work, using cast-off clothing and other fabric at hand, creating unique designs that have garnered worldwide acclaim. Although it declined by the late 1990s, the Freedom Quilting Bee has been rejuvenated, and quilters in Alberta, some the daughters of original members, are selling quilts locally and nationwide. In 2003, the quilters of Gee’s Bend established the Gee’s Bend Quilters’ Collective to promote their work.

Gee’s Bend Quilters

Notable in this era was the creation of the quilting cooperatives among two groups of African American women in south-central Alabama. Both the Gee’s Bend quilting community of Boykin, Wilcox County, and the Freedom Quilting Bee, of nearby Alberta, grew out of the civil rights movement and gained national attention for the bold and innovative designs on their quilts. Self-taught Tuscaloosa artist Yvonne Wells would adopt civil rights themes in her “picture” quilts beginning in the 1980s; her works have been exhibited in the National Museum of African American History and the International Quilt Museum. In 2002, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts produced a major traveling exhibit and accompanying book that brought international attention to Gee’s Bend quilters, to their isolated community, and to the cultural continuity these objects reveal. The quilt makers have continued the same innovative and inspired approach to their work, using cast-off clothing and other fabric at hand, creating unique designs that have garnered worldwide acclaim. Although it declined by the late 1990s, the Freedom Quilting Bee has been rejuvenated, and quilters in Alberta, some the daughters of original members, are selling quilts locally and nationwide. In 2003, the quilters of Gee’s Bend established the Gee’s Bend Quilters’ Collective to promote their work.

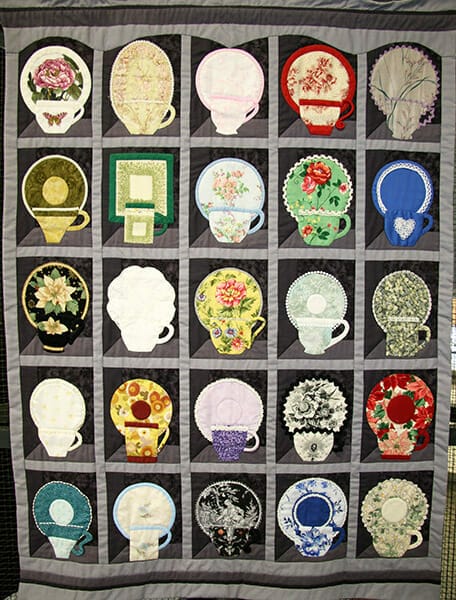

Tea Cup Quilt

In the 1970s, the women’s movement gained momentum, calling attention to the inequalities and lack of opportunity offered to women artists. Many of these artists began creating works that reflected women’s experiences and included woman-focused imagery in their pieces. This era saw a tremendous revival of interest in quilts, with major exhibitions and publications focusing not on just women’s history but on the art of the quilt. Artists in a range of media began experimenting with the possibilities and challenges offered by fabric, and a new group of artists surfaced who chose quilting as their medium. The studio quilt movement blossomed, and Alabama artists began producing vibrant works in the art quilt genre. In addition to the rise of the studio quilt movement, women began to gather in quilting societies or circles to create group and individual projects, mostly based on traditional patterns. These groups range across all demographics of race and economics.

Tea Cup Quilt

In the 1970s, the women’s movement gained momentum, calling attention to the inequalities and lack of opportunity offered to women artists. Many of these artists began creating works that reflected women’s experiences and included woman-focused imagery in their pieces. This era saw a tremendous revival of interest in quilts, with major exhibitions and publications focusing not on just women’s history but on the art of the quilt. Artists in a range of media began experimenting with the possibilities and challenges offered by fabric, and a new group of artists surfaced who chose quilting as their medium. The studio quilt movement blossomed, and Alabama artists began producing vibrant works in the art quilt genre. In addition to the rise of the studio quilt movement, women began to gather in quilting societies or circles to create group and individual projects, mostly based on traditional patterns. These groups range across all demographics of race and economics.

Quilt making—whether from kits, standardized patterns, shared inspiration, or unique individual contributions—continues as a tradition in Alabama. Quilters continue to make their own distinctive contributions to this decorative medium, and strong personal expressions continue among makers of both traditional quilts and studio or art quilts.

Further Reading

- Adams, E. Bryding, ed. Made in Alabama: A State Legacy. Birmingham: Birmingham Museum of Art, 1995.

- Arnett, William, et al. The Quilts of Gee’s Bend: Masterpieces from a Lost Place. Atlanta: Tinwood Publications, 2002.

- Callahan, Nancy. The Freedom Quilting Bee. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987.

- Horton, Laurel, ed. Quiltmaking in America: Beyond the Myths. Nashville, Tenn.: Rutledge Hill Press, 1994.

- Roberts, Elise Schebler. The Quilt: A History and Celebration of an American Art Form. St. Paul, Minn.: Voyageur Press, 2007.